Зобов’язання поважати права людини

Міністерство освіти і науки, молоді та спорту україни

Маріупольський державний університет

КАФЕДРА АНГЛІЙСЬКОЇ МОВИ ТА ПЕРЕКЛАДУ

МЕТОДИЧНИЙ ПОСІБНИК З

ПЕРЕКЛАДАЦЬКОГО АНАЛІЗУ ТЕКСТІВ

Маріуполь – 2011

УДК 42

М 17

ББК 81.432.1- 932.7

Шепітько С.В. Методичний посібник з перекладацького аналізу текстів. Маріуполь: МДУ, 2011.- 148 с.

Рецензенти :

Висоцька Г.В., к.ф.н., доцент кафедри перекладу Приазовського державного технічного університету;

Павленко О.Г., к.ф.н., доцент кафедри англійської мови Маріупольського державного університету.

Посібник призначений для студентів-перекладачів. У посібнику викладено основи перекладацького аналізу текстів різних функціональних стилів мови.

Мета посібника - надати майбутнім перекладачам-практикам необхідні теоретичні та практичні знання у галузі сучасних методик аналізу дискурсу та письмового тексту з метою виявлення у тексті змістового центру, ключових слів, лексико-семантичних зв’язків між словами, що забезпечують когезію тексту, ознайомити студентів з методами швидкого реферування текстів. Посібник також надає студентам основи стилістичного, комунікативно-прагматичного та тендерного аналізу тексту, висвітлює принципи практичного застосування основних перекладацьких трансформацій.

Видається за рішенням вченої ради факультету іноземних мов Маріупольського державного університету від , протокол №

|

|

|

©Шепітько С.В.

СОNTENTS

Передмова……………………………………………………………………..4

Unit 1. Basic notions of text analysis: text and discourse……………………7

Unit 2. Lexical and semantic means of cohesion in text……………………18

Unit 3. Identification of repetition links and creation of a net of bonds in the

text…………………………………………………………………….25

Unit 4. Stylistic analysis of non-fictional texts in the process of translation:

texts of official and business documents…………………………….36

Unit 5. Stylistic analysis of non-fictional texts in the process of translation:

scientific and technical texts…………………………………………46

Unit 6. Stylistic analysis of non-fictional texts in the process of translation:

texts of the publicistic style…………………………………………...56

Unit 7. Stylistic analysis of fictional texts in the process of translation……70

Unit 8. Analysis aimed at identification gender markers of “female” or

“male” language in the text and its importance for translation……82

Unit 9. Pragmatic analysis of texts in the process of translation…………...92

Unit 10. Transformations in translation……………………………………105

Annex 1. The scheme of translator’s text analysis…………………………117

Annex 2. Additional texts for analysis and translation……………………119

ПЕРЕДМОВА

Цей навчально-методичний посібник призначений, перш за все, для студентів - перекладачів. У посібнику викладено основи перекладацького аналізу текстів різних функціональних стилів мови, оскільки адекватний письмовий переклад неможливо здійснити без відповідного перекладацького аналізу вихідного текстового матеріалу. В основу теоретичної частини посібника покладено матеріал посібника Максімова С.Є., Радченко Т.О. Перекладацький аналіз тексту (англійська та українська мови). Курс лекцій та матеріали до семінарських занять. - К.: Вид. центр КНЛУ, 2001; практична частина посібника вміщує тексти для перекладацького аналізу і практичного перекладу, причому акцент зроблено як на аудиторну роботу (семінарські та практичні заняття), так і на самостійну роботу студентів.

|

|

|

Мета посібника полягає у тому, щоб надати майбутнім перекладачам-філологам, спеціалістам та магістрам необхідні для їх майбутньої роботи теоретичні та практичні знання та навички у галузі сучасних методик аналізу дискурсу та письмового тексту з метою виявлення у тексті семантичного ядра (змістового центру), ключових слів, лексико-семантичних зв’язків між словами, що забезпечують когезію (зв’язність) тексту, ознайомити студентів з методами швидкого реферування тексту. Посібник також знайомить студентів з основами стилістичного (жанрового), комунікативно- прагматичного та гендерного (за принципом встановлення різниці між “чоловічою” та “жіночою” мовами) аналізу тексту, висвітлює принципи практичного застосування основних лексико-семантичних та граматичних трансформацій, які здійснюються у практиці перекладу.

|

|

|

Посібник складається з тематичних блоків (units). Кожен із блоків містить теоретичний та ілюстративний матеріал, який можна викладати.у формі лекції, або вивчати самостійно, та матеріалів до відповідних практичних (семінарських) занять та самостійної поза- аудиторної роботи. Матеріали до кожного практичного (семінарського) заняття складаються з основних питань (завдань), які мають бути розглянуті під час аудиторної роботи або виконані самостійно з метою закріплення висвітлених теоретичних положенії, а також текстів, або фрагментів текстів для аналізу та перекладу, списку використаної та рекомендованої наукової та навчально-методичної літератури та глосарію основних лінгвістичних та перекладо- знавчих термінів, вжитих у кожному тематичному блоці.

Ілюстративний матеріал посібника та матеріал для аналізу та перекладу складають англомовні та україномовні тексти різних функціональних стилів. Це тексти офіційно-ділового, науково-технічного, публіцистичного, інформаційного (тексти засобів масової інформації) та художнього стилів. Такий підхід дозволяє ознайомити студентів з методиками перекладацького аналізу як нехудожніх текстів, які виконують комунікативну функцію у суспільстві (це є головною метою посібника і основною роботою професійного пере- кладача-практика), так і художніх текстів, які відображають реальний світ непрямим шляхом через художню уяву митця та реалізують артистичну функцію мови.

|

|

|

Більшість матеріалів посібника (розділи про категорію когезії тексту, лексико-семантичні зв’язки, тендерний та комунікативно- прагматичний аналіз дискурсу, перекладацькі трансформації) базуються на найсучасніших досягненнях вітчизняного та зарубіжного перекладознавства, лінгвістики тексту, соціолінгвістики та психолінгвістики, які було здобуто протягом останніх десятиріч. Це дає підстави вважати, що запропонований посібник буде корисним для перекладачів, філологів, політичних аналітиків, журналістів, психологів та фахівців інших галузей, які мають справу з перекладом письмових текстів.

Ілюстративний матеріал посібника складається з текстів, фрагментів текстів та окремих прикладів, які було взято з вітчизняних та зарубіжних джерел, а саме: Андрюшкин Л.І І. Деловой английский язык (Business English). - СПб.: Норинт, 2000; Живиця. Хрестоматія української літератури XX століття. У двох книгах. / Ред. М.Конончук. - K.: Твім інтер, 1998; Загребельний П.А. Роксолана. - Харків: Євро експрес, 2000; Українська мова. 110 диктантів. Державна підсумкова атестація. 9 кл. / В.І.Тихоша. - K.: КІМО, 2005; Hemingway 1'S. Selected Stories - M.: Progress, 1975; Science Year 1993. - Chicago, London: World Book, Inc., 1993; Topsy-Tuwy World. English Humour in Verse. - M.: Progress: 1978; World’s greatest speeches. - Softbits CD ROM publication, 1994; текстів та фрагментів текстів з газет та журналів, таких як “Вечірній Київ”, “Голос України”, “День", “Демократична Україна”, “Урядовий кур’єр”, “The Daily Telegraph", “The Financial Times”, “Kyiv Post”, “Newsweek”, “Time”, “Panorama”, “The Mirror”, “The Sunday Times”, “The Wall Street Journal", “USA Today” тощо; текстів телевізійних інтерв’ю, міжнародно-правових документів, конвенцій та інших документів Ради Європи та ООН, текстів Конституції України, законів України та постанов Уряду України, матеріалів міжнародних конференцій.

В ілюстративному матеріалі посібника написання українських та англійських слів наводиться згідно з текстами оригіналів. Це стосується, насамперед, авторських неологізмів, просторічної, поетичної, діалектної та стилізованої лексики, а також слів, що мають два рівноцінних варіанти написання (напр, organization та organisation), або належать до різних варіантів однієї мови (напр, британський та американський варіанти англійської мови).

UNIT I

BASIC NOTIONS OF TEXT ANALYSIS: TEXT AND DISCOURSE

Main points:

1.1 Levels of linguistic structure

1.2 Text and discourse

1.3 Cohesion and text organisation: three wavs of viewing the problem

1.4 Artefact and mentafact texts

**********************************************************

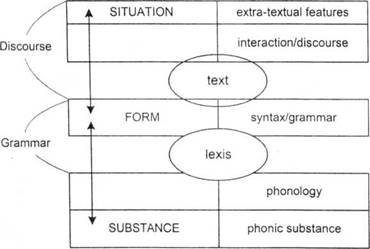

1.1. Levels of linguistic structure

It is generally assumed in modern linguistics that human language is structurally organised. Language structures are levelled and this levelling may be compared with a many-storied building or with a pyramid. Generally speaking, we may assume that people produce sounds to make words, which are then combined into sentences according to the rules of grammar. Sentences are further on combined into texts, which are main units of interaction.

Verbal interaction (communication), either written or oral, always takes place in a certain context or communicative situation. This situation in its turn is embedded into the macro-context of interaction: cultural, social, economic political, historical, etc. In linguistics there are very many writers on this issue expressing different points of view but most of them agree that oral and written texts function in a certain discourse.

1.2. Text and discourse

For practical reasons we will assume the following definitions of text and discourse:

Textis any verbalized (i.e. expressed by means of human language) communicative event performed via (i.e. by means of) human language, no matter whether this communication is performed in written or in oral mode.

It means that we will consider all complete pieces (chunks) of written or oral verbal communication to be texts. This is not the only one approach to the definition of text, as we will discuss later.

Discourse is a complex communicative phenomenon, which includes, besides the text itself, other factors of interaction (such as shared knowledge, communicative goals, cognitive systems of participants, their cultural competence, etc.), i.e. all that is necessary for successful production and adequate interpretation (comprehension and translation) of the text.

|

|

Therefore text is embedded into discourse and both of them are “materialized” in a communicative situation, which in its turn is embedded into the macro-context of interaction: cultural, social, economic, political, historical, religious, etc. The following diagram may graphically represent all the assumptions about levels of linguistic structure that were madeabove [Hoey 1991: 213]:

1.3. Cohesion and text organization: three ways of viewing the problem

There are several important features of text, however the main one is cohesion [see Galperin 1981:73-85; Hoey 1991:3-25].

Cohesion may be defined as the way certain words or grammatical features of a sentence can connect that sentence to its predecessors (and successors) in a text.

Therefore, cohesion helps to understand a text as a whole, to comprehend its topic and to interpret (as well as to translate) text correctly. This feature of text is very important for translators and interpreters as they never translate separate words or sentences but deal with complete texts (oral or written). Lack of cohesion (which sometimes happens with certain speakers and authors) is the most serious challenge for interpreters and translators. Thus cohesion is a property of text as of a linguistic unit.

There exists also another category – coherence, which is understood as a quality assigned to text by a reader or listener, and is a measure of the extent to which the reader or listener finds that the text holds together and makes sense as a unity. Therefore, coherence is a subjective category because certain texts may be found coherent by one reader and incoherent by another one.

In modem linguistics there are three ways of viewing text organization.

The firstis that text has no organization whatsoever and is just a fragment of continuous speech process [see, e.g. Кривоносов 1986]. This view seems to be losing ground, mainly because it contradicts everyday experience.

The second is that text has some organization, but that this organization does not have the status of structure, i.e. does not permit to make predictive statements about the text [Hoey 1991 ]. However, if one looks closely at the British approach to text, one will see that this approach is rather structure-oriented, though, perhaps, aimed more at practical interpretation of texts and not at lengthy theoretical discussions of their structural nature.

The third way of viewing text organization is that text does permit full structural description, can be subject to prediction and computer processing (see works of most European (continental) and American authors, such as T.A. van Dijk, J.Grimes, M.A.K.Halliday and R.Hasan, R.E.Longacre, K.L.Pike and many others). Some authors even claim that any text functions as a “cybernetic system” of speech communication [Брандес, Провоторов 2003].

For the purposes of our analysis we will recognize the third approach [Maksimov 1992] as the one that:

(a) fits into modern theories of semiotics and text linguistics;

(b) fits into modern practice of computer-assisted text processing and existing practices of designing computer software;

(c) satisfies the needs of text analysis in the process of translation.

Indeed, if words in sentences are connected in a certain way with each other and sentences are connected to make up texts, than we may say that there is some structure in a text, which can be comprehended by readers or listeners and properly rendered (translated or interpreted) by means of another language.

1.4. Artefact and mentafact texts

Texts have to be classified in some way. One of the approaches to text classification we will describe below [see: Аспекты 1982; Maksimov 1992; Sinclair 1986].

All texts can be placed on a horizontal scale which shows different functions of texts, the way people use and interpret them, as well as different approaches to translation of texts.

At the one extreme end of the scale there are texts, which demand almost verbal interpretation. Such texts are used either for “changing" the real world or for reporting statements about it, i.e. for “reflecting” the real world. Examples are: texts of constitutions, statutes, laws, international treaties and agreements, conventions, business contracts, protocols, business letters, rules and regulations, etc. (i.e., texts that “change the world”), academic texts of science, medicine and other fields of research which inform the reader about the results of academic studies and outline ways of practical implementation of these results, various reports, news items, etc. (i.e., texts that “reflect the world”). All of these texts are non-fictional texts, which may be labelled as artefact texts.

The second group of texts, which can be placed on the other extreme end of the scale, are those texts, which influence the real world indirectly, through artistic images, and hidden knowledge, which the reader has to infer from them. These are mostly fictional texts of poetry, drama and prose, which may be labelled as mentafact texts. These texts neither change (like texts of laws), nor reflect (like academic texts or texts of news items) the real material world, but describe the fictional world, created in the imagination of the author.

This classification reflects the difference between the communicave function (artefact texts) and artistic function (mentafact texts) of the human language.

Other types of texts are texts of the publicistic (or rather “mass media") style, including editorials, journalistic articles, essays, TV and radio commentaries as well as texts of memoirs, public and political speeches, etc., i.e. texts which deal with the facts of the real world but have certain linguistic features of fictional texts (emotional colouring, author’s evaluation of the events, the use of stylistic devices and expressive means ol the language - everything which is aimed at "persuasion" of the addressee). These texts can be placed between the artefacts and mentafacts in the so-called “grey zone” as they perform persuasive function of human speech.

While performing text analysis and doing practical translation translators have to approach these three basic groups of texts differently, though main principles of translation remain the same.

SEMINAR 1

Questions for discussion and practical assignments:

1. Give the outline of the levels of the language structure. Give reasons why text is regarded as the unit of the highest level of human communication.

2. Give the definition of text and comment upon it.

3. Give the definition of discourse and comment upon the interrelation between text and discourse.

4. What is cohesion and why it is so important for u nderstanding and translating texts?

5. Suggest arguments for distinguishing between cohesion and coherence.

6. What are the different approaches to defining th inguistic nature of text? Which one is the most grounded to your mind?

7. Comment on the difference between artefact and mentafact texts.

8. Give grounds for classifying the following sample texts as artefacts or mentafacts and suggest ways of their analysis and translation:

Text 1.

European Convention on the suppression of terrorism

The member States of the Council of Europe, signatory hereto,

Considering that the aim of the Council of Europe is to achieve a greater

unity between its Members;

(...)

Have agreed as follows:

Article 1. For the purposes of extradition between contracting States, none of the following offences shall be regarded as a political offence or as an offence connected with a political offence or as an offence inspired by political motives:

a) an offence within the scope of the Convention for the Suppression of Unlawful Seizure of Aircraft, signed at the Hague on 16 December 1970;

b) an offence within the scope of the Convention for he Suppression of Unlawful Acts against the Safety of Civil Aviation, signed at Montreal on 23 September 1971;

c) a serious offence involving an attack against the life, physical integrity or liberty of internationally protected persons, including diplomatic agents; (...)

Text 2. Classify the following text as suggested above and compare its Ukrainian version with the English one (Text 1):

КОНВЕНЦІЯ

про захист прав і основних свобод людини Рим 4.ХІ, 1950

із поправками внесеними відповідно до положень Протоколу № 11

Уряди держав - членів Ради Європи, які підписали цю Конвенцію, беручи до уваги Загальну декларацію прав людини, проголошену Генеральною Асамблеєю Організації Об’єднаних Націй 10 грудня 1948 року, враховуючи, що ця Декларація має на меті забезпечити загальне та ефективне визнання і дотримання прав, які в ній проголошені, враховуючи, що метою Ради Європи є досягнення більшого єднання між її членами і що одним із засобів досягнення цієї мети є забезпечення і подальше здійснення прав людини та основних свобод, знову підтверджуючи свою глибоку віру в ті основні свободи, які складають підвалини справедливості і миру в усьому світі і які найкращим чином забезпечуються, з одного боку, завдяки дієвій політичній демократії, а з іншого боку, завдяки загальному розумінню і дотриманню прав людини, від яких вони залежать, сповнені рішучості, як уряди європейських країн, що є однодумцями і мають спільну спадщину політичних традицій, ідеалів, свободи та верховенства права, зробити перші кроки до колективного забезпечення певних прав, проголошених у Загальній декларації, домовилися про таке:

Стаття 1

Зобов’язання поважати права людини

Високі Договірні Сторони гарантують кожному, хто перебуває під їхньою юрисдикцією, права і свободи, визначені в розділі І цієї Конвенції.

Розділ І

Права і свободи

Стаття 2

Право на життя

1. Право кожного на життя охороняється законом. Нікого не може бути умисно позбавлено життя інакше ніж на виконання вироку суду, винесеного після визнання його винним у вчиненні злочину, за який законом передбачене таке покарання.

2. Позбавлення життя не розглядається як таке, що його вчинено на порушення цієї статті, якщо воно є наслідком виключно необхідного застосування сили:

a) при захисті будь-якої особи від незаконного насильства;

b) при здійсненні законного арешту або для запобігання втечі особи, яка законно тримається під вартою;

c)при вчиненні правомірних дій для придушення заворушення або повстання.

Стаття З

Заборона катування

Нікого не може бути піддано катуванню або нелюдському чи такому, що принижує гідність, поводженню або покаранню.

Стаття 4

Заборона рабства та примусової праці

1. Ніхто не може триматися в рабстві або в підневільному стані.

2. Ніхто не може бути присилуваний виконувати примусову чи обов’язкову працю.

3. Для цілей цієї статті значення терміна “примусова чи обов’язкова праця” не поширюється на:

а) будь-яку роботу, виконання якої звичайно вимагається під час тримання під вартою, призначеного згідно з положеннями статті 5 цієї Конвенції, або під час умовного звільнення з-під варти;

b) будь-яку службу військового характеру або - у випадку, коли особа відмовляється від неї з релігійних чи політичних мотивів у .країнах, де така відмова визнається, - службу, яка мас виконуватися замість обов’язкової військової служби;

c) будь-яку службу, яка має виконуватися у випадку надзвичайної ситуації або стихійного лиха, що загрожує життю чи благополуччю суспільства;

d) будь-яку роботу чи службу, яка входить у звичайні громадянські обов’язки.

Text 3.

Surrender by Britain on beef ban

The Government faced the anger of farmers last night after bowing to pressure from Europe to slaughter tens of thousands more cattle in an attempt to win agreement on a framework for a step-by-step lifting of the worldwide ban on British beef. Twenty-four hours earlier Douglas Hogg, the Agricultural Minister, described as “quite untrue” reports that an increased cattle cull was being considered.

He said that it was “not on the table” in the negotiations with the Brussels. Yesterday he denied that there had been a “cave in”, arguing that the Government had tried to respond to sensible proposals.

Farmers leaders and Opposition politicians accused the Government of a “climb-down” after it emerged that the European Commission’s latest proposals for lifting the ban did not contain any firm date - although the Government expects an easing of the ban by the autumn. Robin Cook, Labour’s foreign affairs spokesman, said the Government had settled for a “piece of paper that contains no dates and no guarantees” and “surrendered” to the demands for an extra cull”.

The Daily Telegraph

Text 4.

Осінній етюд

Вже стояла пополудня пора. Повітря давно посухішало, й запахи в повітрі також посохли. Павутинка бабиного літа пропливла паче химерний літальний засіб із незнаної цивілізації осені, й на ньому пролетіли невидимі посланці осені, її причаєні інопланетяни.

Поміж зів’ялої, похнюпленої трави снувалась до лісу стежечка. Дерева стояли де звільна, де пнулись по сторчкуватих схилах.

Стежечка вив'юнилась до велетенського кряжистого дуба на чистій, поснованій низькою травою галяві, звідки інші дерева начебто зумисне повідступали не те що в оторопілому, а в спокійному захопленні перед цим велетнем придніпровського лісу.

І чим ближче я підходив до врочистого велетня, тим він більшав у моїх очах, виростав у височінь, ширшав, розпросторювався кроною. Велич його також побільшувалась, водночас начебто грізнішаючи. І коли я опинився зовсім близько, так, що зміг долонею торкнутись чорно-червоної, репаної, твердої кори, тоді дуб затулив од мене не тільки прив’ялу блакить неба, а й частину довколишнього лісу. Він мовби прийняв мене в свої обійми.

І коли я стояв під могутнім віковим дубом, я начебто переродився. Я дивився не тільки своїми очима, а й чужими, я сприймав світ не тільки своєю душею, а й чужою, з якою моя душа була нерозривно споріднена.

Є.Гуцало

Text 5.

There was an old Person of Ewell,

Who chiefly subsisted on gruel;

But to make it more nice, he inserted some mice,

Which refreshed that Old Person of Ewell

Topsy-Turvy World

Text 6.

Чи ми були людьми, чи ні –

У тій недавній давнині,

Коли боялися тюрми і смерті –

чи були людьми?

Були, були, бо той наш страх

Горів і лазив, як мурах,

По серці - він кусав і пік,

На пекло обертав наш вік;

О, ця свобода, що прийшла,

Летить на мене, як бджола

З жалом смертельним, але я

Вже не боюсь! О, це моя

Звитяга! Отже, люто й зло

Вганяй своє тяжке жало!

Дмитро Павличко

LITERATURE

1. Аспекты общей и частной лингвистической теории текста. М.: Наука, 1982. - 192 с.

2. Брандес М.П., Провоторов В.И. Предпереводческий анализ текста/ М.П. Брандес, В.И. Провоторов. - М.: НВИ-ТЕЗАУРУС, 2003. - 224 с.

3. Гальперин И.Р. Текст как объект лингвистического исслсдования/ И.Р. Гальперин - М.: Наука, 1981. - 139с.

4. Дейк Т.А. ван. Язык, познание, коммуникация / Т.А ван. Дейк. - М.: Прогресс. 1989.-312 с.

5. Кривоносов А. Т. «Лингвистика текста» и исследование взаимоотношения языка и мышления/ А. Т. Кривоносов // Вопр.языкознания, 1986. - С. 23-27.

6. Halliday М.А.К. Categories of the theory of grammar/ М.А.К. Halliday // Word, 1961, Vol. 17, N 3.- P. 241-292.

7. Hoey M. Patterns of Lexis in Text/ M. Hoey.- Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 1991.-276 p.

8. Maksimov S.E. Deictic Markers as Linguistic Means of Expressing Authority in Text : Diss... Master of Arts in Special Applications of Linguistics. - Birmingham, 1992. - 121 p.

9. Sinclair J. Fictional worlds //Talking about text/ J. Sinclair - Birmingham: English Language Research, DAM № 13. - P. 43-60.

Дата добавления: 2018-08-06; просмотров: 1695; Мы поможем в написании вашей работы! |

Мы поможем в написании ваших работ!