How Your Habits Shape Your Identity (and

Vice Versa)

| W |

HY IS IT so easy to repeat bad habits and so hard to form good ones? Few things can have a more powerful impact on your life

than improving your daily habits. And yet it is likely that this time next year you’ll be doing the same thing rather than something better.

It often feels difficult to keep good habits going for more than a few days, even with sincere effort and the occasional burst of motivation. Habits like exercise, meditation, journaling, and cooking are reasonable for a day or two and then become a hassle.

However, once your habits are established, they seem to stick around forever—especially the unwanted ones. Despite our best intentions, unhealthy habits like eating junk food, watching too much television, procrastinating, and smoking can feel impossible to break.

Changing our habits is challenging for two reasons: (1) we try to change the wrong thing and (2) we try to change our habits in the wrong way. In this chapter, I’ll address the first point. In the chapters that follow, I’ll answer the second.

Our first mistake is that we try to change the wrong thing. To understand what I mean, consider that there are three levels at which change can occur. You can imagine them like the layers of an onion.

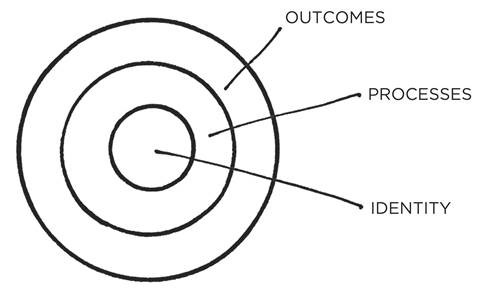

THREE LAYERS OF BEHAVIOR CHANGE

FIGURE 3: There are three layers of behavior change: a change in your outcomes, a change in your processes, or a change in your identity.

The first layer is changing your outcomes. This level is concerned with changing your results: losing weight, publishing a book, winning a championship. Most of the goals you set are associated with this level of change.

The second layer is changing your process. This level is concerned with changing your habits and systems: implementing a new routine at the gym, decluttering your desk for better workflow, developing a meditation practice. Most of the habits you build are associated with this level.

|

|

|

The third and deepest layer is changing your identity. This level is concerned with changing your beliefs: your worldview, your self-image, your judgments about yourself and others. Most of the beliefs, assumptions, and biases you hold are associated with this level.

Outcomes are about what you get. Processes are about what you do. Identity is about what you believe. When it comes to building habits that last—when it comes to building a system of 1 percent improvements—the problem is not that one level is “better” or “worse” than another. All levels of change are useful in their own way. The problem is the direction of change.

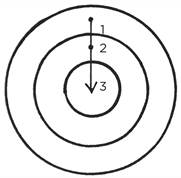

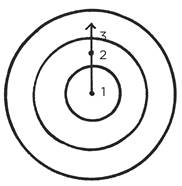

Many people begin the process of changing their habits by focusing on what they want to achieve. This leads us to outcome-based habits. The alternative is to build identity-based habits. With this approach, we start by focusing on who we wish to become.

OUTCOME-BASED HABITS

IDENTITY-BASED HABITS

FIGURE 4: With outcome-based habits, the focus is on what you want to achieve. With identity-based habits, the focus is on who you wish to become.

Imagine two people resisting a cigarette. When offered a smoke, the first person says, “No thanks. I’m trying to quit.” It sounds like a reasonable response, but this person still believes they are a smoker who is trying to be something else. They are hoping their behavior will change while carrying around the same beliefs.

The second person declines by saying, “No thanks. I’m not a smoker.” It’s a small difference, but this statement signals a shift in identity. Smoking was part of their former life, not their current one. They no longer identify as someone who smokes.

|

|

|

Most people don’t even consider identity change when they set out to improve. They just think, “I want to be skinny (outcome) and if I stick to this diet, then I’ll be skinny (process).” They set goals and determine the actions they should take to achieve those goals without considering the beliefs that drive their actions. They never shift the way they look at themselves, and they don’t realize that their old identity can sabotage their new plans for change.

Behind every system of actions are a system of beliefs. The system of a democracy is founded on beliefs like freedom, majority rule, and social equality. The system of a dictatorship has a very different set of beliefs like absolute authority and strict obedience. You can imagine many ways to try to get more people to vote in a democracy, but such behavior change would never get off the ground in a dictatorship. That’s not the identity of the system. Voting is a behavior that is impossible under a certain set of beliefs.

A similar pattern exists whether we are discussing individuals, organizations, or societies. There are a set of beliefs and assumptions that shape the system, an identity behind the habits.

Behavior that is incongruent with the self will not last. You may want more money, but if your identity is someone who consumes rather than creates, then you’ll continue to be pulled toward spending rather than earning. You may want better health, but if you continue to prioritize comfort over accomplishment, you’ll be drawn to relaxing rather than training. It’s hard to change your habits if you never change the underlying beliefs that led to your past behavior. You have a new goal and a new plan, but you haven’t changed who you are.

|

|

|

The story of Brian Clark, an entrepreneur from Boulder, Colorado, provides a good example. “For as long as I can remember, I’ve chewed my fingernails,” Clark told me. “It started as a nervous habit when I was young, and then morphed into an undesirable grooming ritual. One day, I resolved to stop chewing my nails until they grew out a bit. Through mindful willpower alone, I managed to do it.” Then, Clark did something surprising.

“I asked my wife to schedule my first-ever manicure,” he said. “My thought was that if I started paying to maintain my nails, I wouldn’t chew them. And it worked, but not for the monetary reason. What happened was the manicure made my fingers look really nice for the first time. The manicurist even said that—other than the chewing—I had really healthy, attractive nails. Suddenly, I was proud of my fingernails. And even though that’s something I had never aspired to, it made all the difference. I’ve never chewed my nails since; not even a single close call. And it’s because I now take pride in properly caring for them.”

The ultimate form of intrinsic motivation is when a habit becomes part of your identity. It’s one thing to say I’m the type of person who wants this. It’s something very different to say I’m the type of person who is this.

The more pride you have in a particular aspect of your identity, the more motivated you will be to maintain the habits associated with it. If you’re proud of how your hair looks, you’ll develop all sorts of habits to care for and maintain it. If you’re proud of the size of your biceps, you’ll make sure you never skip an upper-body workout. If you’re proud of the scarves you knit, you’ll be more likely to spend hours knitting each week. Once your pride gets involved, you’ll fight tooth and nail to maintain your habits.

|

|

|

True behavior change is identity change. You might start a habit because of motivation, but the only reason you’ll stick with one is that it becomes part of your identity. Anyone can convince themselves to visit the gym or eat healthy once or twice, but if you don’t shift the belief behind the behavior, then it is hard to stick with long-term changes. Improvements are only temporary until they become part of who you are.

The goal is not to read a book, the goal is to become a reader.

The goal is not to read a book, the goal is to become a reader.

The goal is not to run a marathon, the goal is to become a runner.

The goal is not to learn an instrument, the goal is to become a musician.

Your behaviors are usually a reflection of your identity. What you do is an indication of the type of person you believe that you are—either consciously or nonconsciously.* Research has shown that once a person believes in a particular aspect of their identity, they are more likely to act in alignment with that belief. For example, people who identified as “being a voter” were more likely to vote than those who simply claimed “voting” was an action they wanted to perform. Similarly, the person who incorporates exercise into their identity doesn’t have to convince themselves to train. Doing the right thing is easy. After all, when your behavior and your identity are fully aligned, you are no longer pursuing behavior change. You are simply acting like the type of person you already believe yourself to be.

Like all aspects of habit formation, this, too, is a double-edged sword. When working for you, identity change can be a powerful force for self-improvement. When working against you, though, identity change can be a curse. Once you have adopted an identity, it can be easy to let your allegiance to it impact your ability to change. Many people walk through life in a cognitive slumber, blindly following the norms attached to their identity.

“I’m terrible with directions.”

“I’m terrible with directions.”

“I’m not a morning person.”

“I’m bad at remembering people’s names.”

“I’m always late.”

“I’m not good with technology.”

“I’m horrible at math.”

. . . and a thousand other variations.

When you have repeated a story to yourself for years, it is easy to slide into these mental grooves and accept them as a fact. In time, you begin to resist certain actions because “that’s not who I am.” There is internal pressure to maintain your self-image and behave in a way that is consistent with your beliefs. You find whatever way you can to avoid contradicting yourself.

The more deeply a thought or action is tied to your identity, the more difficult it is to change it. It can feel comfortable to believe what your culture believes (group identity) or to do what upholds your selfimage (personal identity), even if it’s wrong. The biggest barrier to positive change at any level—individual, team, society—is identity conflict. Good habits can make rational sense, but if they conflict with your identity, you will fail to put them into action.

On any given day, you may struggle with your habits because you’re too busy or too tired or too overwhelmed or hundreds of other reasons. Over the long run, however, the real reason you fail to stick with habits is that your self-image gets in the way. This is why you can’t get too attached to one version of your identity. Progress requires unlearning.

Becoming the best version of yourself requires you to continuously edit your beliefs, and to upgrade and expand your identity.

This brings us to an important question: If your beliefs and worldview play such an important role in your behavior, where do they come from in the first place? How, exactly, is your identity formed? And how can you emphasize new aspects of your identity that serve you and gradually erase the pieces that hinder you?

Дата добавления: 2019-09-02; просмотров: 490; Мы поможем в написании вашей работы! |

Мы поможем в написании ваших работ!