HABIT STACKING: A SIMPLE PLAN TO OVERHAUL YOUR HABITS

The French philosopher Denis Diderot lived nearly his entire life in poverty, but that all changed one day in 1765.

Diderot’s daughter was about to be married and he could not afford to pay for the wedding. Despite his lack of wealth, Diderot was well known for his role as the co-founder and writer of Encyclopédie, one of the most comprehensive encyclopedias of the time. When Catherine the Great, the Empress of Russia, heard of Diderot’s financial troubles, her heart went out to him. She was a book lover and greatly enjoyed his encyclopedia. She offered to buy Diderot’s personal library for £1,000 —more than $150,000 today.* Suddenly, Diderot had money to spare. With his new wealth, he not only paid for the wedding but also acquired a scarlet robe for himself.

Diderot’s scarlet robe was beautiful. So beautiful, in fact, that he immediately noticed how out of place it seemed when surrounded by his more common possessions. He wrote that there was “no more coordination, no more unity, no more beauty” between his elegant robe and the rest of his stuff.

Diderot soon felt the urge to upgrade his possessions. He replaced his rug with one from Damascus. He decorated his home with expensive sculptures. He bought a mirror to place above the mantel, and a better kitchen table. He tossed aside his old straw chair for a leather one. Like falling dominoes, one purchase led to the next.

Diderot’s behavior is not uncommon. In fact, the tendency for one purchase to lead to another one has a name: the Diderot Effect. The Diderot Effect states that obtaining a new possession often creates a spiral of consumption that leads to additional purchases.

You can spot this pattern everywhere. You buy a dress and have to get new shoes and earrings to match. You buy a couch and suddenly question the layout of your entire living room. You buy a toy for your child and soon find yourself purchasing all of the accessories that go with it. It’s a chain reaction of purchases.

|

|

|

Many human behaviors follow this cycle. You often decide what to do next based on what you have just finished doing. Going to the bathroom leads to washing and drying your hands, which reminds you that you need to put the dirty towels in the laundry, so you add laundry detergent to the shopping list, and so on. No behavior happens in isolation. Each action becomes a cue that triggers the next behavior.

Why is this important?

When it comes to building new habits, you can use the connectedness of behavior to your advantage. One of the best ways to build a new habit is to identify a current habit you already do each day and then stack your new behavior on top. This is called habit stacking.

Habit stacking is a special form of an implementation intention. Rather than pairing your new habit with a particular time and location, you pair it with a current habit. This method, which was created by BJ Fogg as part of his Tiny Habits program, can be used to design an obvious cue for nearly any habit.*

The habit stacking formula is:

“After [CURRENT HABIT], I will [NEW HABIT].” For example:

Meditation. After I pour my cup of coffee each morning, I will meditate for one minute.

Meditation. After I pour my cup of coffee each morning, I will meditate for one minute.

Exercise. After I take off my work shoes, I will immediately change into my workout clothes.

Exercise. After I take off my work shoes, I will immediately change into my workout clothes.

Gratitude. After I sit down to dinner, I will say one thing I’m grateful for that happened today.

Gratitude. After I sit down to dinner, I will say one thing I’m grateful for that happened today.

Marriage. After I get into bed at night, I will give my partner a kiss.

Marriage. After I get into bed at night, I will give my partner a kiss.

Safety. After I put on my running shoes, I will text a friend or family member where I am running and how long it will take.

Safety. After I put on my running shoes, I will text a friend or family member where I am running and how long it will take.

The key is to tie your desired behavior into something you already do each day. Once you have mastered this basic structure, you can begin to create larger stacks by chaining small habits together. This allows you to take advantage of the natural momentum that comes from one behavior leading into the next—a positive version of the Diderot Effect.

|

|

|

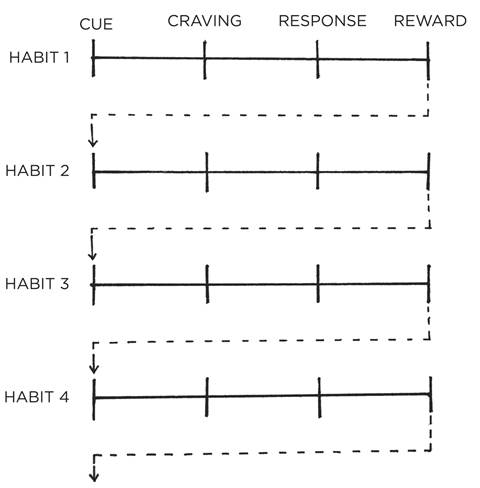

HABIT STACKING

FIGURE 7: Habit stacking increases the likelihood that you’ll stick with a habit by stacking your new behavior on top of an old one. This process can be repeated to chain numerous habits together, each one acting as the cue for the next.

Your morning routine habit stack might look like this:

1. After I pour my morning cup of coffee, I will meditate for sixty seconds.

2. After I meditate for sixty seconds, I will write my to-do list for the day.

3. After I write my to-do list for the day, I will immediately begin my first task.

Or, consider this habit stack in the evening:

1. After I finish eating dinner, I will put my plate directly into the dishwasher.

2. After I put my dishes away, I will immediately wipe down the counter.

3. After I wipe down the counter, I will set out my coffee mug for tomorrow morning.

You can also insert new behaviors into the middle of your current routines. For example, you may already have a morning routine that looks like this: Wake up > Make my bed > Take a shower. Let’s say you want to develop the habit of reading more each night. You can expand your habit stack and try something like: Wake up > Make my bed > Place a book on my pillow > Take a shower. Now, when you climb into bed each night, a book will be sitting there waiting for you to enjoy.

Overall, habit stacking allows you to create a set of simple rules that guide your future behavior. It’s like you always have a game plan for which action should come next. Once you get comfortable with this approach, you can develop general habit stacks to guide you whenever the situation is appropriate:

|

|

|

Exercise. When I see a set of stairs, I will take them instead of using the elevator.

Exercise. When I see a set of stairs, I will take them instead of using the elevator.

Social skills. When I walk into a party, I will introduce myself to someone I don’t know yet.

Social skills. When I walk into a party, I will introduce myself to someone I don’t know yet.

Finances. When I want to buy something over $100, I will wait twenty-four hours before purchasing.

Finances. When I want to buy something over $100, I will wait twenty-four hours before purchasing.

Healthy eating. When I serve myself a meal, I will always put veggies on my plate first.

Healthy eating. When I serve myself a meal, I will always put veggies on my plate first.

Minimalism. When I buy a new item, I will give something away. (“One in, one out.”)

Minimalism. When I buy a new item, I will give something away. (“One in, one out.”)

Mood. When the phone rings, I will take one deep breath and smile before answering.

Mood. When the phone rings, I will take one deep breath and smile before answering.

Forgetfulness. When I leave a public place, I will check the table and chairs to make sure I don’t leave anything behind.

Forgetfulness. When I leave a public place, I will check the table and chairs to make sure I don’t leave anything behind.

No matter how you use this strategy, the secret to creating a successful habit stack is selecting the right cue to kick things off. Unlike an implementation intention, which specifically states the time and location for a given behavior, habit stacking implicitly has the time and location built into it. When and where you choose to insert a habit into your daily routine can make a big difference. If you’re trying to add meditation into your morning routine but mornings are chaotic and your kids keep running into the room, then that may be the wrong place and time. Consider when you are most likely to be successful. Don’t ask yourself to do a habit when you’re likely to be occupied with something else.

|

|

|

Your cue should also have the same frequency as your desired habit. If you want to do a habit every day, but you stack it on top of a habit that only happens on Mondays, that’s not a good choice.

One way to find the right trigger for your habit stack is by brainstorming a list of your current habits. You can use your Habits Scorecard from the last chapter as a starting point. Alternatively, you can create a list with two columns. In the first column, write down the habits you do each day without fail.* For example:

Get out of bed.

Get out of bed.

Take a shower.

Brush your teeth.

Get dressed.

Brew a cup of coffee.

Eat breakfast.

Take the kids to school.

Start the work day.

Eat lunch.

End the work day.

Change out of work clothes.

Sit down for dinner.

Turn off the lights.

Turn off the lights.

Get into bed.

Your list can be much longer, but you get the idea. In the second column, write down all of the things that happen to you each day without fail. For example:

The sun rises.

The sun rises.

You get a text message.

The song you are listening to ends.

The sun sets.

Armed with these two lists, you can begin searching for the best place to layer your new habit into your lifestyle.

Habit stacking works best when the cue is highly specific and immediately actionable. Many people select cues that are too vague. I made this mistake myself. When I wanted to start a push-up habit, my habit stack was “When I take a break for lunch, I will do ten push-ups.” At first glance, this sounded reasonable. But soon, I realized the trigger was unclear. Would I do my push-ups before I ate lunch? After I ate lunch? Where would I do them? After a few inconsistent days, I changed my habit stack to: “When I close my laptop for lunch, I will do ten push-ups next to my desk.” Ambiguity gone.

Habits like “read more” or “eat better” are worthy causes, but these goals do not provide instruction on how and when to act. Be specific and clear: After I close the door. After I brush my teeth. After I sit down at the table. The specificity is important. The more tightly bound your new habit is to a specific cue, the better the odds are that you will notice when the time comes to act.

The 1st Law of Behavior Change is to make it obvious. Strategies like implementation intentions and habit stacking are among the most practical ways to create obvious cues for your habits and design a clear plan for when and where to take action.

Chapter Summary

The 1st Law of Behavior Change is make it obvious.

The 1st Law of Behavior Change is make it obvious.

The two most common cues are time and location.

The two most common cues are time and location.

Creating an implementation intention is a strategy you can use to pair a new habit with a specific time and location.

The implementation intention formula is: I will [BEHAVIOR] at [TIME] in [LOCATION].

The implementation intention formula is: I will [BEHAVIOR] at [TIME] in [LOCATION].

Habit stacking is a strategy you can use to pair a new habit with a current habit.

Habit stacking is a strategy you can use to pair a new habit with a current habit.

The habit stacking formula is: After [CURRENT HABIT], I will [NEW HABIT].

The habit stacking formula is: After [CURRENT HABIT], I will [NEW HABIT].

6

Motivation Is Overrated; Environment

Often Matters More

ANNE THORNDIKE, A primary care physician at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, had a crazy idea. She believed she could improve the eating habits of thousands of hospital staff and visitors without changing their willpower or motivation in the slightest way. In fact, she didn’t plan on talking to them at all.

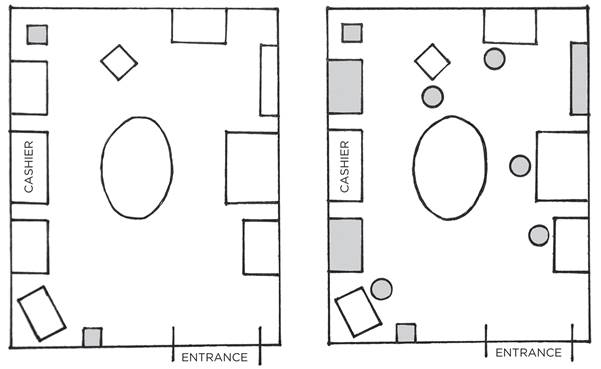

Thorndike and her colleagues designed a six-month study to alter the “choice architecture” of the hospital cafeteria. They started by changing how drinks were arranged in the room. Originally, the refrigerators located next to the cash registers in the cafeteria were filled with only soda. The researchers added water as an option to each one. Additionally, they placed baskets of bottled water next to the food stations throughout the room. Soda was still in the primary refrigerators, but water was now available at all drink locations.

Over the next three months, the number of soda sales at the hospital dropped by 11.4 percent. Meanwhile, sales of bottled water increased by 25.8 percent. They made similar adjustments—and saw similar results—with the food in the cafeteria. Nobody had said a word to anyone eating there.

BEFORE AFTER

FIGURE 8: Here is a representation of what the cafeteria looked like before the environment design changes were made (left) and after (right). The shaded boxes indicate areas where bottled water was available in each instance. Because the amount of water in the environment was increased, behavior shifted naturally and without additional motivation.

People often choose products not because of what they are, but because of where they are. If I walk into the kitchen and see a plate of cookies on the counter, I’ll pick up half a dozen and start eating, even if I hadn’t been thinking about them beforehand and didn’t necessarily feel hungry. If the communal table at the office is always filled with doughnuts and bagels, it’s going to be hard not to grab one every now and then. Your habits change depending on the room you are in and the cues in front of you.

Environment is the invisible hand that shapes human behavior. Despite our unique personalities, certain behaviors tend to arise again and again under certain environmental conditions. In church, people tend to talk in whispers. On a dark street, people act wary and guarded. In this way, the most common form of change is not internal, but external: we are changed by the world around us. Every habit is context dependent.

In 1936, psychologist Kurt Lewin wrote a simple equation that makes a powerful statement: Behavior is a function of the Person in their Environment, or B = f (P,E).

It didn’t take long for Lewin’s Equation to be tested in business. In

1952, the economist Hawkins Stern described a phenomenon he called Suggestion Impulse Buying, which “is triggered when a shopper sees a product for the first time and visualizes a need for it.” In other words, customers will occasionally buy products not because they want them but because of how they are presented to them.

For example, items at eye level tend to be purchased more than those down near the floor. For this reason, you’ll find expensive brand names featured in easy-to-reach locations on store shelves because they drive the most profit, while cheaper alternatives are tucked away in harder-to-reach spots. The same goes for end caps, which are the units at the end of aisles. End caps are moneymaking machines for retailers because they are obvious locations that encounter a lot of foot traffic. For example, 45 percent of Coca-Cola sales come specifically from end-of-the-aisle racks.

The more obviously available a product or service is, the more likely you are to try it. People drink Bud Light because it is in every bar and visit Starbucks because it is on every corner. We like to think that we are in control. If we choose water over soda, we assume it is because we wanted to do so. The truth, however, is that many of the actions we take each day are shaped not by purposeful drive and choice but by the most obvious option.

Every living being has its own methods for sensing and understanding the world. Eagles have remarkable long-distance vision. Snakes can smell by “tasting the air” with their highly sensitive tongues. Sharks can detect small amounts of electricity and vibrations in the water caused by nearby fish. Even bacteria have chemoreceptors —tiny sensory cells that allow them to detect toxic chemicals in their environment.

In humans, perception is directed by the sensory nervous system. We perceive the world through sight, sound, smell, touch, and taste. But we also have other ways of sensing stimuli. Some are conscious, but many are nonconscious. For instance, you can “notice” when the temperature drops before a storm, or when the pain in your gut rises during a stomachache, or when you fall off balance while walking on rocky ground. Receptors in your body pick up on a wide range of internal stimuli, such as the amount of salt in your blood or the need to drink when thirsty.

The most powerful of all human sensory abilities, however, is vision.

The human body has about eleven million sensory receptors. Approximately ten million of those are dedicated to sight. Some experts estimate that half of the brain’s resources are used on vision. Given that we are more dependent on vision than on any other sense, it should come as no surprise that visual cues are the greatest catalyst of our behavior. For this reason, a small change in what you see can lead to a big shift in what you do. As a result, you can imagine how important it is to live and work in environments that are filled with productive cues and devoid of unproductive ones.

Thankfully, there is good news in this respect. You don’t have to be the victim of your environment. You can also be the architect of it.

Дата добавления: 2019-09-02; просмотров: 440; Мы поможем в написании вашей работы! |

Мы поможем в написании ваших работ!