HOW LONG DOES IT ACTUALLY TAKE TO FORM A NEW HABIT?

Habit formation is the process by which a behavior becomes progressively more automatic through repetition. The more you repeat an activity, the more the structure of your brain changes to become efficient at that activity. Neuroscientists call this long-term potentiation, which refers to the strengthening of connections between neurons in the brain based on recent patterns of activity. With each repetition, cell-to-cell signaling improves and the neural connections tighten. First described by neuropsychologist Donald Hebb in 1949, this phenomenon is commonly known as Hebb’s Law: “Neurons that fire together wire together.”

Repeating a habit leads to clear physical changes in the brain. In musicians, the cerebellum—critical for physical movements like plucking a guitar string or pulling a violin bow—is larger than it is in nonmusicians. Mathematicians, meanwhile, have increased gray matter in the inferior parietal lobule, which plays a key role in computation and calculation. Its size is directly correlated with the amount of time spent in the field; the older and more experienced the mathematician, the greater the increase in gray matter.

When scientists analyzed the brains of taxi drivers in London, they found that the hippocampus—a region of the brain involved in spatial memory—was significantly larger in their subjects than in non–taxi drivers. Even more fascinating, the hippocampus decreased in size when a driver retired. Like the muscles of the body responding to regular weight training, particular regions of the brain adapt as they are used and atrophy as they are abandoned.

Of course, the importance of repetition in establishing habits was recognized long before neuroscientists began poking around. In 1860, the English philosopher George H. Lewes noted, “In learning to speak a new language, to play on a musical instrument, or to perform unaccustomed movements, great difficulty is felt, because the channels through which each sensation has to pass have not become established; but no sooner has frequent repetition cut a pathway, than this difficulty vanishes; the actions become so automatic that they can be performed while the mind is otherwise engaged.” Both common sense and scientific evidence agree: repetition is a form of change.

|

|

|

Each time you repeat an action, you are activating a particular neural circuit associated with that habit. This means that simply putting in your reps is one of the most critical steps you can take to encoding a new habit. It is why the students who took tons of photos improved their skills while those who merely theorized about perfect photos did not. One group engaged in active practice, the other in passive learning. One in action, the other in motion.

All habits follow a similar trajectory from effortful practice to automatic behavior, a process known as automaticity. Automaticity is the ability to perform a behavior without thinking about each step, which occurs when the nonconscious mind takes over.

It looks something like this:

THE HABIT LINE

FIGURE 11: In the beginning (point A), a habit requires a good deal of effort and concentration to perform. After a few repetitions (point B), it gets easier, but still requires some conscious attention. With enough practice (point C), the habit becomes more automatic than conscious. Beyond this threshold —the habit line—the behavior can be done more or less without thinking. A new habit has been formed.

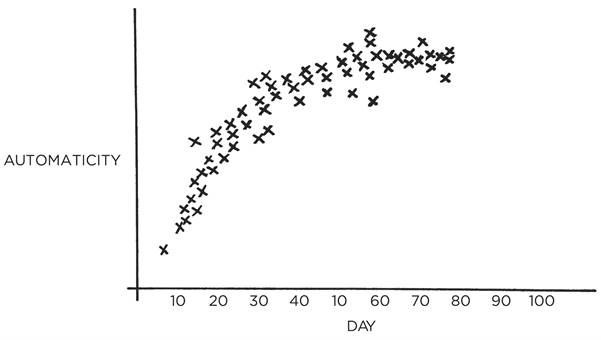

On the following page, you’ll see what it looks like when researchers track the level of automaticity for an actual habit like walking for ten minutes each day. The shape of these charts, which scientists call learning curves, reveals an important truth about behavior change: habits form based on frequency, not time.

|

|

|

WALKING 10 MINUTES PER DAY

FIGURE 12: This graph shows someone who built the habit of walking for ten minutes after breakfast each day. Notice that as the repetitions increase, so does automaticity, until the behavior is as easy and automatic as it can be.

One of the most common questions I hear is, “How long does it take to build a new habit?” But what people really should be asking is, “How many does it take to form a new habit?” That is, how many repetitions are required to make a habit automatic?

There is nothing magical about time passing with regard to habit formation. It doesn’t matter if it’s been twenty-one days or thirty days or three hundred days. What matters is the rate at which you perform the behavior. You could do something twice in thirty days, or two hundred times. It’s the frequency that makes the difference. Your current habits have been internalized over the course of hundreds, if not thousands, of repetitions. New habits require the same level of frequency. You need to string together enough successful attempts until the behavior is firmly embedded in your mind and you cross the Habit Line.

In practice, it doesn’t really matter how long it takes for a habit to become automatic. What matters is that you take the actions you need to take to make progress. Whether an action is fully automatic is of less importance.

To build a habit, you need to practice it. And the most effective way to make practice happen is to adhere to the 3rd Law of Behavior Change: make it easy. The chapters that follow will show you how to do exactly that.

|

|

|

Chapter Summary

The 3rd Law of Behavior Change is make it easy.

The 3rd Law of Behavior Change is make it easy.

The most effective form of learning is practice, not planning. Focus on taking action, not being in motion.

Habit formation is the process by which a behavior becomes progressively more automatic through repetition.

The amount of time you have been performing a habit is not as important as the number of times you have performed it.

The amount of time you have been performing a habit is not as important as the number of times you have performed it.

12

The Law of Least Effort

| I |

N HIS AWARD-WINNING BOOK, Guns, Germs, and Steel, anthropologist and biologist Jared Diamond points out a simple fact: different

continents have different shapes. At first glance, this statement seems rather obvious and unimportant, but it turns out to have a profound impact on human behavior.

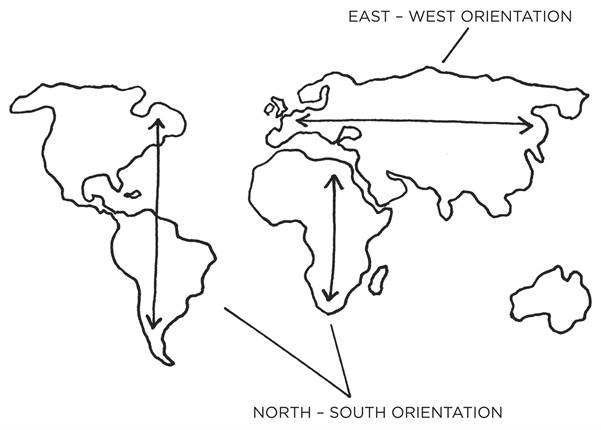

The primary axis of the Americas runs from north to south. That is, the landmass of North and South America tends to be tall and thin rather than wide and fat. The same is generally true for Africa. Meanwhile, the landmass that makes up Europe, Asia, and the Middle East is the opposite. This massive stretch of land tends to be more eastwest in shape. According to Diamond, this difference in shape played a significant role in the spread of agriculture over the centuries.

When agriculture began to spread around the globe, farmers had an easier time expanding along east-west routes than along north-south ones. This is because locations along the same latitude generally share similar climates, amounts of sunlight and rainfall, and changes in season. These factors allowed farmers in Europe and Asia to domesticate a few crops and grow them along the entire stretch of land from France to China.

|

|

|

THE SHAPE OF HUMAN BEHAVIOR

FIGURE 13: The primary axis of Europe and Asia is east-west. The primary axis of the Americas and Africa is north-south. This leads to a wider range of climates up-and-down the Americas than across Europe and Asia. As a result, agriculture spread nearly twice as fast across Europe and Asia than it did elsewhere. The behavior of farmers—even across hundreds or thousands of years—was constrained by the amount of friction in the environment.

By comparison, the climate varies greatly when traveling from north to south. Just imagine how different the weather is in Florida compared to Canada. You can be the most talented farmer in the world, but it won’t help you grow Florida oranges in the Canadian winter. Snow is a poor substitute for soil. In order to spread crops along north-south routes, farmers would need to find and domesticate new plants whenever the climate changed.

As a result, agriculture spread two to three times faster across Asia and Europe than it did up and down the Americas. Over the span of centuries, this small difference had a very big impact. Increased food production allowed for more rapid population growth. With more people, these cultures were able to build stronger armies and were better equipped to develop new technologies. The changes started out small—a crop that spread slightly farther, a population that grew slightly faster—but compounded into substantial differences over time.

The spread of agriculture provides an example of the 3rd Law of Behavior Change on a global scale. Conventional wisdom holds that motivation is the key to habit change. Maybe if you really wanted it, you’d actually do it. But the truth is, our real motivation is to be lazy and to do what is convenient. And despite what the latest productivity best seller will tell you, this is a smart strategy, not a dumb one.

Energy is precious, and the brain is wired to conserve it whenever possible. It is human nature to follow the Law of Least Effort, which states that when deciding between two similar options, people will naturally gravitate toward the option that requires the least amount of work.* For example, expanding your farm to the east where you can grow the same crops rather than heading north where the climate is different. Out of all the possible actions we could take, the one that is realized is the one that delivers the most value for the least effort. We are motivated to do what is easy.

Every action requires a certain amount of energy. The more energy required, the less likely it is to occur. If your goal is to do a hundred push-ups per day, that’s a lot of energy! In the beginning, when you’re motivated and excited, you can muster the strength to get started. But after a few days, such a massive effort feels exhausting. Meanwhile, sticking to the habit of doing one push-up per day requires almost no energy to get started. And the less energy a habit requires, the more likely it is to occur.

Look at any behavior that fills up much of your life and you’ll see that it can be performed with very low levels of motivation. Habits like scrolling on our phones, checking email, and watching television steal so much of our time because they can be performed almost without effort. They are remarkably convenient.

In a sense, every habit is just an obstacle to getting what you really want. Dieting is an obstacle to getting fit. Meditation is an obstacle to feeling calm. Journaling is an obstacle to thinking clearly. You don’t actually want the habit itself. What you really want is the outcome the habit delivers. The greater the obstacle—that is, the more difficult the habit—the more friction there is between you and your desired end state. This is why it is crucial to make your habits so easy that you’ll do them even when you don’t feel like it. If you can make your good habits more convenient, you’ll be more likely to follow through on them.

But what about all the moments when we seem to do the opposite? If we’re all so lazy, then how do you explain people accomplishing hard things like raising a child or starting a business or climbing Mount Everest?

Certainly, you are capable of doing very hard things. The problem is that some days you feel like doing the hard work and some days you feel like giving in. On the tough days, it’s crucial to have as many things working in your favor as possible so that you can overcome the challenges life naturally throws your way. The less friction you face, the easier it is for your stronger self to emerge. The idea behind make it easy is not to only do easy things. The idea is to make it as easy as possible in the moment to do things that payoff in the long run.

Дата добавления: 2019-09-02; просмотров: 313; Мы поможем в написании вашей работы! |

Мы поможем в написании ваших работ!