How to Stop Procrastinating by Using the

Two-Minute Rule

| T |

WYLA THARP IS widely regarded as one of the greatest dancers and choreographers of the modern era. In 1992, she was awarded a MacArthur Fellowship, often referred to as the Genius Grant, and she has spent the bulk of her career touring the globe to perform her original works. She also credits much of her success to simple daily habits.

“I begin each day of my life with a ritual,” she writes. “I wake up at 5:30 A.M., put on my workout clothes, my leg warmers, my sweat shirt, and my hat. I walk outside my Manhattan home, hail a taxi, and tell the driver to take me to the Pumping Iron gym at 91st Street and First Avenue, where I work out for two hours.

“The ritual is not the stretching and weight training I put my body through each morning at the gym; the ritual is the cab. The moment I tell the driver where to go I have completed the ritual.

“It’s a simple act, but doing it the same way each morning habitualizes it—makes it repeatable, easy to do. It reduces the chance that I would skip it or do it differently. It is one more item in my arsenal of routines, and one less thing to think about.”

Hailing a cab each morning may be a tiny action, but it is a splendid example of the 3rd Law of Behavior Change.

Researchers estimate that 40 to 50 percent of our actions on any given day are done out of habit. This is already a substantial percentage, but the true influence of your habits is even greater than these numbers suggest. Habits are automatic choices that influence the conscious decisions that follow. Yes, a habit can be completed in just a few seconds, but it can also shape the actions that you take for minutes or hours afterward.

Habits are like the entrance ramp to a highway. They lead you down a path and, before you know it, you’re speeding toward the next behavior. It seems to be easier to continue what you are already doing than to start doing something different. You sit through a bad movie for two hours. You keep snacking even when you’re already full. You check your phone for “just a second” and soon you have spent twenty minutes staring at the screen. In this way, the habits you follow without thinking often determine the choices you make when you are thinking.

|

|

|

Each evening, there is a tiny moment—usually around 5:15 p.m.— that shapes the rest of my night. My wife walks in the door from work and either we change into our workout clothes and head to the gym or we crash onto the couch, order Indian food, and watch The Office.* Similar to Twyla Tharp hailing the cab, the ritual is changing into my workout clothes. If I change clothes, I know the workout will happen. Everything that follows—driving to the gym, deciding which exercises to do, stepping under the bar—is easy once I’ve taken the first step.

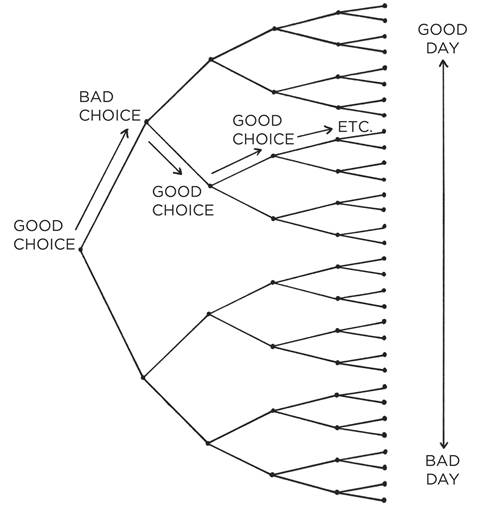

Every day, there are a handful of moments that deliver an outsized impact. I refer to these little choices as decisive moments. The moment you decide between ordering takeout or cooking dinner. The moment you choose between driving your car or riding your bike. The moment you decide between starting your homework or grabbing the video game controller. These choices are a fork in the road.

DECISIVE MOMENTS

FIGURE 14: The difference between a good day and a bad day is often a few productive and healthy choices made at decisive moments. Each one is like a fork in the road, and these choices stack up throughout the day and can ultimately lead to very different outcomes.

Decisive moments set the options available to your future self. For instance, walking into a restaurant is a decisive moment because it determines what you’ll be eating for lunch. Technically, you are in control of what you order, but in a larger sense, you can only order an item if it is on the menu. If you walk into a steakhouse, you can get a sirloin or a rib eye, but not sushi. Your options are constrained by what’s available. They are shaped by the first choice.

|

|

|

We are limited by where our habits lead us. This is why mastering the decisive moments throughout your day is so important. Each day is made up of many moments, but it is really a few habitual choices that determine the path you take. These little choices stack up, each one setting the trajectory for how you spend the next chunk of time.

Habits are the entry point, not the end point. They are the cab, not the gym.

THE TWO-MINUTE RULE

Even when you know you should start small, it’s easy to start too big. When you dream about making a change, excitement inevitably takes over and you end up trying to do too much too soon. The most effective way I know to counteract this tendency is to use the Two-Minute Rule, which states, “When you start a new habit, it should take less than two minutes to do.”

You’ll find that nearly any habit can be scaled down into a twominute version:

“Read before bed each night” becomes “Read one page.”

“Read before bed each night” becomes “Read one page.”

“Do thirty minutes of yoga” becomes “Take out my yoga mat.”

“Study for class” becomes “Open my notes.”

“Fold the laundry” becomes “Fold one pair of socks.”

“Run three miles” becomes “Tie my running shoes.”

The idea is to make your habits as easy as possible to start. Anyone can meditate for one minute, read one page, or put one item of clothing away. And, as we have just discussed, this is a powerful strategy because once you’ve started doing the right thing, it is much easier to continue doing it. A new habit should not feel like a challenge. The actions that follow can be challenging, but the first two minutes should be easy. What you want is a “gateway habit” that naturally leads you down a more productive path.

|

|

|

You can usually figure out the gateway habits that will lead to your desired outcome by mapping out your goals on a scale from “very easy” to “very hard.” For instance, running a marathon is very hard. Running a 5K is hard. Walking ten thousand steps is moderately difficult. Walking ten minutes is easy. And putting on your running shoes is very easy. Your goal might be to run a marathon, but your gateway habit is to put on your running shoes. That’s how you follow the Two-Minute Rule.

| Very easy | Easy | Moderate | Hard | Very hard |

| Put on your running shoes | Walk ten minutes | Walk ten thousand steps | Run a 5K | Run a marathon |

| Write one sentence | Write one paragraph | Write one thousand words | Write a five-thousandword article | Write a book |

| Open your notes | Study for ten minutes | Study for three hours | Get straight A’s | Earn a PhD |

People often think it’s weird to get hyped about reading one page or meditating for one minute or making one sales call. But the point is not to do one thing. The point is to master the habit of showing up. The truth is, a habit must be established before it can be improved. If you can’t learn the basic skill of showing up, then you have little hope of mastering the finer details. Instead of trying to engineer a perfect habit from the start, do the easy thing on a more consistent basis. You have to standardize before you can optimize.

|

|

|

As you master the art of showing up, the first two minutes simply become a ritual at the beginning of a larger routine. This is not merely a hack to make habits easier but actually the ideal way to master a difficult skill. The more you ritualize the beginning of a process, the more likely it becomes that you can slip into the state of deep focus that is required to do great things. By doing the same warm-up before every workout, you make it easier to get into a state of peak performance. By following the same creative ritual, you make it easier to get into the hard work of creating. By developing a consistent power-down habit, you make it easier to get to bed at a reasonable time each night. You may not be able to automate the whole process, but you can make the first action mindless. Make it easy to start and the rest will follow.

The Two-Minute Rule can seem like a trick to some people. You know that the real goal is to do more than just two minutes, so it may feel like you’re trying to fool yourself. Nobody is actually aspiring to read one page or do one push-up or open their notes. And if you know it’s a mental trick, why would you fall for it?

If the Two-Minute Rule feels forced, try this: do it for two minutes and then stop. Go for a run, but you must stop after two minutes. Start meditating, but you must stop after two minutes. Study Arabic, but you must stop after two minutes. It’s not a strategy for starting, it’s the whole thing. Your habit can only last one hundred and twenty seconds.

One of my readers used this strategy to lose over one hundred pounds. In the beginning, he went to the gym each day, but he told himself he wasn’t allowed to stay for more than five minutes. He would go to the gym, exercise for five minutes, and leave as soon as his time was up. After a few weeks, he looked around and thought, “Well, I’m always coming here anyway. I might as well start staying a little longer.” A few years later, the weight was gone.

Journaling provides another example. Nearly everyone can benefit from getting their thoughts out of their head and onto paper, but most people give up after a few days or avoid it entirely because journaling feels like a chore.* The secret is to always stay below the point where it feels like work. Greg McKeown, a leadership consultant from the United Kingdom, built a daily journaling habit by specifically writing less than he felt like. He always stopped journaling before it seemed like a hassle. Ernest Hemingway believed in similar advice for any kind of writing. “The best way is to always stop when you are going good,” he said.

Strategies like this work for another reason, too: they reinforce the identity you want to build. If you show up at the gym five days in a row —even if it’s just for two minutes—you are casting votes for your new identity. You’re not worried about getting in shape. You’re focused on becoming the type of person who doesn’t miss workouts. You’re taking the smallest action that confirms the type of person you want to be.

We rarely think about change this way because everyone is consumed by the end goal. But one push-up is better than not exercising. One minute of guitar practice is better than none at all. One minute of reading is better than never picking up a book. It’s better to do less than you hoped than to do nothing at all.

At some point, once you’ve established the habit and you’re showing up each day, you can combine the Two-Minute Rule with a technique we call habit shaping to scale your habit back up toward your ultimate goal. Start by mastering the first two minutes of the smallest version of the behavior. Then, advance to an intermediate step and repeat the process—focusing on just the first two minutes and mastering that stage before moving on to the next level. Eventually, you’ll end up with the habit you had originally hoped to build while still keeping your focus where it should be: on the first two minutes of the behavior.

EXAMPLES OF HABIT SHAPING

| Becoming an Early Riser |

| Phase 1: Be home by 10 p.m. every night. Phase 2: Have all devices (TV, phone, etc.) turned off by 10 p.m. every night. Phase 3: Be in bed by 10 p.m. every night (reading a book, talking with your partner). Phase 4: Lights off by 10 p.m. every night. Phase 5: Wake up at 6 a.m. every day. |

| Becoming Vegan |

| Phase 1: Start eating vegetables at each meal. Phase 2: Stop eating animals with four legs (cow, pig, lamb, etc.). Phase 3: Stop eating animals with two legs (chicken, turkey, etc.). Phase 4: Stop eating animals with no legs (fish, clams, scallops, etc.). Phase 5: Stop eating all animal products (eggs, milk, cheese). |

| Starting to Exercise |

| Phase 1: Change into workout clothes. Phase 2: Step out the door (try taking a walk). Phase 3: Drive to the gym, exercise for five minutes, and leave. Phase 4: Exercise for fifteen minutes at least once per week. Phase 5: Exercise three times per week. |

Nearly any larger life goal can be transformed into a two-minute behavior. I want to live a healthy and long life > I need to stay in shape > I need to exercise > I need to change into my workout clothes. I want to have a happy marriage > I need to be a good partner > I should do something each day to make my partner’s life easier > I should meal plan for next week.

Whenever you are struggling to stick with a habit, you can employ the Two-Minute Rule. It’s a simple way to make your habits easy.

Chapter Summary

Habits can be completed in a few seconds but continue to impact your behavior for minutes or hours afterward.

Habits can be completed in a few seconds but continue to impact your behavior for minutes or hours afterward.

Many habits occur at decisive moments—choices that are like a fork in the road—and either send you in the direction of a productive day or an unproductive one.

Many habits occur at decisive moments—choices that are like a fork in the road—and either send you in the direction of a productive day or an unproductive one.

The Two-Minute Rule states, “When you start a new habit, it should take less than two minutes to do.”

The Two-Minute Rule states, “When you start a new habit, it should take less than two minutes to do.”

The more you ritualize the beginning of a process, the more likely it becomes that you can slip into the state of deep focus that is required to do great things.

The more you ritualize the beginning of a process, the more likely it becomes that you can slip into the state of deep focus that is required to do great things.

Standardize before you optimize. You can’t improve a habit that doesn’t exist.

Standardize before you optimize. You can’t improve a habit that doesn’t exist.

14

How to Make Good Habits Inevitable and Bad Habits Impossible

| I |

N THE SUMMER OF 1830, Victor Hugo was facing an impossible deadline.

Twelve months earlier, the French author had promised his publisher a new book. But instead of writing, he spent that year pursuing other projects, entertaining guests, and delaying his work. Frustrated, Hugo’s publisher responded by setting a deadline less than six months away. The book had to be finished by February 1831.

Hugo concocted a strange plan to beat his procrastination. He collected all of his clothes and asked an assistant to lock them away in a large chest. He was left with nothing to wear except a large shawl. Lacking any suitable clothing to go outdoors, he remained in his study and wrote furiously during the fall and winter of 1830. The Hunchback of Notre Dame was published two weeks early on January 14, 1831.*

Sometimes success is less about making good habits easy and more about making bad habits hard. This is an inversion of the 3rd Law of Behavior Change: make it difficult. If you find yourself continually struggling to follow through on your plans, then you can take a page from Victor Hugo and make your bad habits more difficult by creating what psychologists call a commitment device.

A commitment device is a choice you make in the present that controls your actions in the future. It is a way to lock in future behavior, bind you to good habits, and restrict you from bad ones. When Victor Hugo shut his clothes away so he could focus on writing, he was creating a commitment device.*

There are many ways to create a commitment device. You can reduce overeating by purchasing food in individual packages rather than in bulk size. You can voluntarily ask to be added to the banned list at casinos and online poker sites to prevent future gambling sprees. I’ve even heard of athletes who have to “make weight” for a competition choosing to leave their wallets at home during the week before weigh-in so they won’t be tempted to buy fast food.

As another example, my friend and fellow habits expert Nir Eyal purchased an outlet timer, which is an adapter that he plugged in between his internet router and the power outlet. At 10 p.m. each night, the outlet timer cuts off the power to the router. When the internet goes off, everyone knows it is time to go to bed.

Commitment devices are useful because they enable you to take advantage of good intentions before you can fall victim to temptation. Whenever I’m looking to cut calories, for example, I will ask the waiter to split my meal and box half of it to go before the meal is served. If I waited until the meal came out and told myself “I’ll just eat half,” it would never work.

The key is to change the task such that it requires more work to get out of the good habit than to get started on it. If you’re feeling motivated to get in shape, schedule a yoga session and pay ahead of time. If you’re excited about the business you want to start, email an entrepreneur you respect and set up a consulting call. When the time comes to act, the only way to bail is to cancel the meeting, which requires effort and may cost money.

Commitment devices increase the odds that you’ll do the right thing in the future by making bad habits difficult in the present. However, we can do even better. We can make good habits inevitable and bad habits impossible.

Дата добавления: 2019-09-02; просмотров: 273; Мы поможем в написании вашей работы! |

Мы поможем в написании ваших работ!