THE DOPAMINE-DRIVEN FEEDBACK LOOP

Scientists can track the precise moment a craving occurs by measuring a neurotransmitter called dopamine.* The importance of dopamine became apparent in 1954 when the neuroscientists James Olds and Peter Milner ran an experiment that revealed the neurological processes behind craving and desire. By implanting electrodes in the brains of rats, the researchers blocked the release of dopamine. To the surprise of the scientists, the rats lost all will to live. They wouldn’t eat. They wouldn’t have sex. They didn’t crave anything. Within a few days, the animals died of thirst.

In follow-up studies, other scientists also inhibited the dopaminereleasing parts of the brain, but this time, they squirted little droplets of sugar into the mouths of the dopamine-depleted rats. Their little rat faces lit up with pleasurable grins from the tasty substance. Even though dopamine was blocked, they liked the sugar just as much as before; they just didn’t want it anymore. The ability to experience pleasure remained, but without dopamine, desire died. And without desire, action stopped.

When other researchers reversed this process and flooded the reward system of the brain with dopamine, animals performed habits at breakneck speed. In one study, mice received a powerful hit of dopamine each time they poked their nose in a box. Within minutes, the mice developed a craving so strong they began poking their nose into the box eight hundred times per hour. (Humans are not so different: the average slot machine player will spin the wheel six hundred times per hour.)

Habits are a dopamine-driven feedback loop. Every behavior that is highly habit-forming—taking drugs, eating junk food, playing video games, browsing social media—is associated with higher levels of dopamine. The same can be said for our most basic habitual behaviors like eating food, drinking water, having sex, and interacting socially.

For years, scientists assumed dopamine was all about pleasure, but now we know it plays a central role in many neurological processes, including motivation, learning and memory, punishment and aversion, and voluntary movement.

When it comes to habits, the key takeaway is this: dopamine is released not only when you experience pleasure, but also when you anticipate it. Gambling addicts have a dopamine spike right before they place a bet, not after they win. Cocaine addicts get a surge of dopamine when they see the powder, not after they take it. Whenever you predict that an opportunity will be rewarding, your levels of dopamine spike in anticipation. And whenever dopamine rises, so does your motivation to act.

It is the anticipation of a reward—not the fulfillment of it—that gets us to take action.

Interestingly, the reward system that is activated in the brain when you receive a reward is the same system that is activated when you anticipate a reward. This is one reason the anticipation of an experience can often feel better than the attainment of it. As a child, thinking about Christmas morning can be better than opening the gifts. As an adult, daydreaming about an upcoming vacation can be more enjoyable than actually being on vacation. Scientists refer to this as the difference between “wanting” and “liking.”

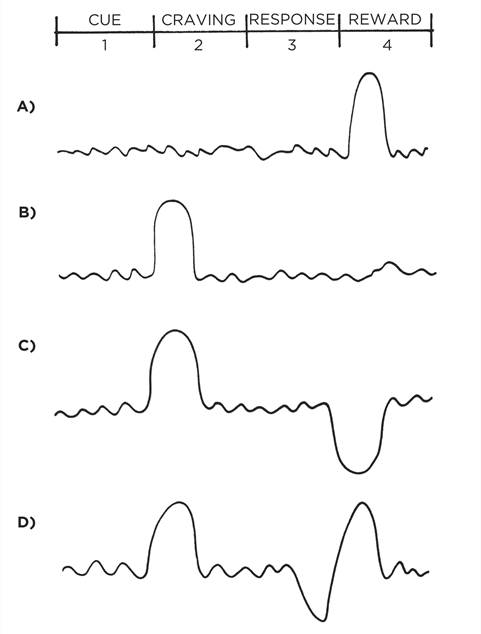

THE DOPAMINE SPIKE

FIGURE 9: Before a habit is learned (A), dopamine is released when the reward is experienced for the first time. The next time around (B), dopamine rises before taking action, immediately after a cue is recognized. This spike leads to a feeling of desire and a craving to take action whenever the cue is spotted. Once a habit is learned, dopamine will not rise when a reward is experienced because you already expect the reward. However, if you see a cue and expect a reward, but do not get one, then dopamine will drop in disappointment (C). The sensitivity of the dopamine response can clearly be seen when a reward is provided late (D). First, the cue is identified and dopamine rises as a craving builds. Next, a response is taken but the reward does not come as quickly as expected and dopamine begins to drop. Finally, when the reward comes a little later than you had hoped, dopamine spikes again. It is as if the brain is saying, “See! I knew I was right. Don’t forget to repeat this action next time.”

Your brain has far more neural circuitry allocated for wanting rewards than for liking them. The wanting centers in the brain are large: the brain stem, the nucleus accumbens, the ventral tegmental area, the dorsal striatum, the amygdala, and portions of the prefrontal cortex. By comparison, the liking centers of the brain are much smaller. They are often referred to as “hedonic hot spots” and are distributed like tiny islands throughout the brain. For instance, researchers have found that 100 percent of the nucleus accumbens is activated during wanting. Meanwhile, only 10 percent of the structure is activated during liking.

The fact that the brain allocates so much precious space to the regions responsible for craving and desire provides further evidence of the crucial role these processes play. Desire is the engine that drives behavior. Every action is taken because of the anticipation that precedes it. It is the craving that leads to the response.

These insights reveal the importance of the 2nd Law of Behavior Change. We need to make our habits attractive because it is the expectation of a rewarding experience that motivates us to act in the first place. This is where a strategy known as temptation bundling comes into play.

Дата добавления: 2019-09-02; просмотров: 603; Мы поможем в написании вашей работы! |

Мы поможем в написании ваших работ!