The Role of Family and Friends in Shaping

Your Habits

| I |

N 1965, a Hungarian man named Laszlo Polgar wrote a series of strange letters to a woman named Klara.

Laszlo was a firm believer in hard work. In fact, it was all he believed in: he completely rejected the idea of innate talent. He claimed that with deliberate practice and the development of good habits, a child could become a genius in any field. His mantra was “A genius is not born, but is educated and trained.”

Laszlo believed in this idea so strongly that he wanted to test it with his own children—and he was writing to Klara because he “needed a wife willing to jump on board.” Klara was a teacher and, although she may not have been as adamant as Laszlo, she also believed that with proper instruction, anyone could advance their skills.

Laszlo decided chess would be a suitable field for the experiment, and he laid out a plan to raise his children to become chess prodigies. The kids would be home-schooled, a rarity in Hungary at the time. The house would be filled with chess books and pictures of famous chess players. The children would play against each other constantly and compete in the best tournaments they could find. The family would keep a meticulous file system of the tournament history of every competitor the children faced. Their lives would be dedicated to chess.

Laszlo successfully courted Klara, and within a few years, the Polgars were parents to three young girls: Susan, Sofia, and Judit.

Susan, the oldest, began playing chess when she was four years old.

Within six months, she was defeating adults.

Sofia, the middle child, did even better. By fourteen, she was a world champion, and a few years later, she became a grandmaster.

Judit, the youngest, was the best of all. By age five, she could beat her father. At twelve, she was the youngest player ever listed among the top one hundred chess players in the world. At fifteen years and four months old, she became the youngest grandmaster of all time— younger than Bobby Fischer, the previous record holder. For twentyseven years, she was the number-one-ranked female chess player in the world.

|

|

|

The childhood of the Polgar sisters was atypical, to say the least. And yet, if you ask them about it, they claim their lifestyle was attractive, even enjoyable. In interviews, the sisters talk about their childhood as entertaining rather than grueling. They loved playing chess. They couldn’t get enough of it. Once, Laszlo reportedly found Sofia playing chess in the bathroom in the middle of the night. Encouraging her to go back to sleep, he said, “Sofia, leave the pieces alone!” To which she replied, “Daddy, they won’t leave me alone!”

The Polgar sisters grew up in a culture that prioritized chess above all else—praised them for it, rewarded them for it. In their world, an obsession with chess was normal. And as we are about to see, whatever habits are normal in your culture are among the most attractive behaviors you’ll find.

THE SEDUCTIVE PULL OF SOCIAL NORMS

Humans are herd animals. We want to fit in, to bond with others, and to earn the respect and approval of our peers. Such inclinations are essential to our survival. For most of our evolutionary history, our ancestors lived in tribes. Becoming separated from the tribe—or worse, being cast out—was a death sentence. “The lone wolf dies, but the pack survives.”*

Meanwhile, those who collaborated and bonded with others enjoyed increased safety, mating opportunities, and access to resources. As Charles Darwin noted, “In the long history of humankind, those who learned to collaborate and improvise most effectively have prevailed.” As a result, one of the deepest human desires is to belong. And this ancient preference exerts a powerful influence on our modern behavior.

|

|

|

We don’t choose our earliest habits, we imitate them. We follow the script handed down by our friends and family, our church or school, our local community and society at large. Each of these cultures and groups comes with its own set of expectations and standards—when and whether to get married, how many children to have, which holidays to celebrate, how much money to spend on your child’s birthday party. In many ways, these social norms are the invisible rules that guide your behavior each day. You’re always keeping them in mind, even if they are at the not top of your mind. Often, you follow the habits of your culture without thinking, without questioning, and sometimes without remembering. As the French philosopher Michel de Montaigne wrote, “The customs and practices of life in society sweep us along.”

Most of the time, going along with the group does not feel like a burden. Everyone wants to belong. If you grow up in a family that rewards you for your chess skills, playing chess will seem like a very attractive thing to do. If you work in a job where everyone wears expensive suits, then you’ll be inclined to splurge on one as well. If all of your friends are sharing an inside joke or using a new phrase, you’ll want to do it, too, so they know that you “get it.” Behaviors are attractive when they help us fit in.

We imitate the habits of three groups in particular:

1. The close.

2. The many.

3. The powerful.

Each group offers an opportunity to leverage the 2nd Law of Behavior Change and make our habits more attractive.

1. Imitating the Close

|

|

|

Proximity has a powerful effect on our behavior. This is true of the physical environment, as we discussed in Chapter 6, but it is also true of the social environment.

We pick up habits from the people around us. We copy the way our parents handle arguments, the way our peers flirt with one another, the way our coworkers get results. When your friends smoke pot, you give it a try, too. When your wife has a habit of double-checking that the door is locked before going to bed, you pick it up as well.

I find that I often imitate the behavior of those around me without realizing it. In conversation, I’ll automatically assume the body posture of the other person. In college, I began to talk like my roommates. When traveling to other countries, I unconsciously imitate the local accent despite reminding myself to stop.

As a general rule, the closer we are to someone, the more likely we are to imitate some of their habits. One groundbreaking study tracked twelve thousand people for thirty-two years and found that “a person’s chances of becoming obese increased by 57 percent if he or she had a friend who became obese.” It works the other way, too. Another study found that if one person in a relationship lost weight, the other partner would also slim down about one third of the time. Our friends and family provide a sort of invisible peer pressure that pulls us in their direction.

Of course, peer pressure is bad only if you’re surrounded by bad influences. When astronaut Mike Massimino was a graduate student at MIT, he took a small robotics class. Of the ten people in the class, four became astronauts. If your goal was to make it into space, then that room was about the best culture you could ask for. Similarly, one study found that the higher your best friend’s IQ at age eleven or twelve, the higher your IQ would be at age fifteen, even after controlling for natural levels of intelligence. We soak up the qualities and practices of those around us.

|

|

|

One of the most effective things you can do to build better habits is to join a culture where your desired behavior is the normal behavior. New habits seem achievable when you see others doing them every day. If you are surrounded by fit people, you’re more likely to consider working out to be a common habit. If you’re surrounded by jazz lovers, you’re more likely to believe it’s reasonable to play jazz every day. Your culture sets your expectation for what is “normal.” Surround yourself with people who have the habits you want to have yourself. You’ll rise together.

To make your habits even more attractive, you can take this strategy one step further.

Join a culture where (1) your desired behavior is the normal behavior and (2) you already have something in common with the group. Steve Kamb, an entrepreneur in New York City, runs a company called Nerd Fitness, which “helps nerds, misfits, and mutants lose weight, get strong, and get healthy.” His clients include video game lovers, movie fanatics, and average Joes who want to get in shape. Many people feel out of place the first time they go to the gym or try to change their diet, but if you are already similar to the other members of the group in some way—say, your mutual love of Star Wars—change becomes more appealing because it feels like something people like you already do.

Nothing sustains motivation better than belonging to the tribe. It transforms a personal quest into a shared one. Previously, you were on your own. Your identity was singular. You are a reader. You are a musician. You are an athlete. When you join a book club or a band or a cycling group, your identity becomes linked to those around you. Growth and change is no longer an individual pursuit. We are readers. We are musicians. We are cyclists. The shared identity begins to reinforce your personal identity. This is why remaining part of a group after achieving a goal is crucial to maintaining your habits. It’s friendship and community that embed a new identity and help behaviors last over the long run.

2. Imitating the Many

In the 1950s, psychologist Solomon Asch conducted a series of experiments that are now taught to legions of undergrads each year. To begin each experiment, the subject entered the room with a group of strangers. Unbeknownst to them, the other participants were actors planted by the researcher and instructed to deliver scripted answers to certain questions.

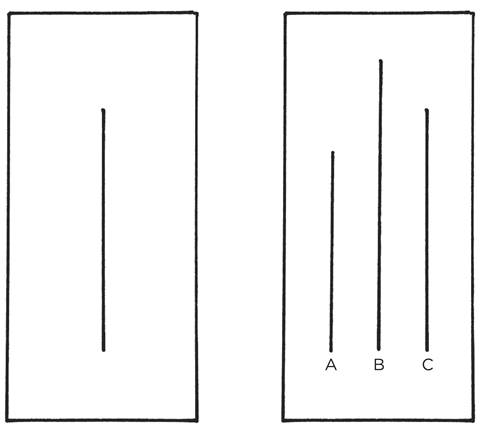

The group would be shown one card with a line on it and then a second card with a series of lines. Each person was asked to select the line on the second card that was similar in length to the line on the first card. It was a very simple task. Here is an example of two cards used in the experiment:

CONFORMING TO SOCIAL NORMS

FIGURE 10: This is a representation of two cards used by Solomon Asch in his famous social conformity experiments. The length of the line on the first card (left) is obviously the same as line C, but when a group of actors claimed it was a different length the research subjects would often change their minds and go with the crowd rather than believe their own eyes.

The experiment always began the same. First, there would be some easy trials where everyone agreed on the correct line. After a few rounds, the participants were shown a test that was just as obvious as the previous ones, except the actors in the room would select an intentionally incorrect answer. For example, they would respond “A” to the comparison shown in Figure 10. Everyone would agree that the lines were the same even though they were clearly different.

The subject, who was unaware of the ruse, would immediately become bewildered. Their eyes would open wide. They would laugh nervously to themselves. They would double-check the reactions of other participants. Their agitation would grow as one person after another delivered the same incorrect response. Soon, the subject began to doubt their own eyes. Eventually, they delivered the answer they knew in their heart to be incorrect.

Asch ran this experiment many times and in many different ways. What he discovered was that as the number of actors increased, so did the conformity of the subject. If it was just the subject and one actor, then there was no effect on the person’s choice. They just assumed they were in the room with a dummy. When two actors were in the room with the subject, there was still little impact. But as the number of people increased to three actors and four and all the way to eight, the subject became more likely to second-guess themselves. By the end of the experiment, nearly 75 percent of the subjects had agreed with the group answer even though it was obviously incorrect.

Whenever we are unsure how to act, we look to the group to guide our behavior. We are constantly scanning our environment and wondering, “What is everyone else doing?” We check reviews on Amazon or Yelp or TripAdvisor because we want to imitate the “best” buying, eating, and travel habits. It’s usually a smart strategy. There is evidence in numbers.

But there can be a downside.

The normal behavior of the tribe often overpowers the desired behavior of the individual. For example, one study found that when a chimpanzee learns an effective way to crack nuts open as a member of one group and then switches to a new group that uses a less effective strategy, it will avoid using the superior nut cracking method just to blend in with the rest of the chimps.

Humans are similar. There is tremendous internal pressure to comply with the norms of the group. The reward of being accepted is often greater than the reward of winning an argument, looking smart, or finding truth. Most days, we’d rather be wrong with the crowd than be right by ourselves.

The human mind knows how to get along with others. It wants to get along with others. This is our natural mode. You can override it— you can choose to ignore the group or to stop caring what other people think—but it takes work. Running against the grain of your culture requires extra effort.

When changing your habits means challenging the tribe, change is unattractive. When changing your habits means fitting in with the tribe, change is very attractive.

3. Imitating the Powerful

Humans everywhere pursue power, prestige, and status. We want pins and medallions on our jackets. We want President or Partner in our titles. We want to be acknowledged, recognized, and praised. This tendency can seem vain, but overall, it’s a smart move. Historically, a person with greater power and status has access to more resources, worries less about survival, and proves to be a more attractive mate.

We are drawn to behaviors that earn us respect, approval, admiration, and status. We want to be the one in the gym who can do muscle-ups or the musician who can play the hardest chord progressions or the parent with the most accomplished children because these things separate us from the crowd. Once we fit in, we start looking for ways to stand out.

This is one reason we care so much about the habits of highly effective people. We try to copy the behavior of successful people because we desire success ourselves. Many of our daily habits are imitations of people we admire. You replicate the marketing strategies of the most successful firms in your industry. You make a recipe from your favorite baker. You borrow the storytelling strategies of your favorite writer. You mimic the communication style of your boss. We imitate people we envy.

High-status people enjoy the approval, respect, and praise of others. And that means if a behavior can get us approval, respect, and praise, we find it attractive.

We are also motivated to avoid behaviors that would lower our status. We trim our hedges and mow our lawn because we don’t want to be the slob of the neighborhood. When our mother comes to visit, we clean up the house because we don’t want to be judged. We are continually wondering “What will others think of me?” and altering our behavior based on the answer.

The Polgar sisters—the chess prodigies mentioned at the beginning of this chapter—are evidence of the powerful and lasting impact social influences can have on our behavior. The sisters practiced chess for many hours each day and continued this remarkable effort for decades. But these habits and behaviors maintained their attractiveness, in part, because they were valued by their culture. From the praise of their parents to the achievement of different status markers like becoming a grandmaster, they had many reasons to continue their effort.

Chapter Summary

The culture we live in determines which behaviors are attractive to us.

The culture we live in determines which behaviors are attractive to us.

We tend to adopt habits that are praised and approved of by our culture because we have a strong desire to fit in and belong to the tribe.

We tend to adopt habits that are praised and approved of by our culture because we have a strong desire to fit in and belong to the tribe.

We tend to imitate the habits of three social groups: the close (family and friends), the many (the tribe), and the powerful (those with status and prestige).

We tend to imitate the habits of three social groups: the close (family and friends), the many (the tribe), and the powerful (those with status and prestige).

One of the most effective things you can do to build better habits is to join a culture where (1) your desired behavior is the normal behavior and (2) you already have something in common with the group.

One of the most effective things you can do to build better habits is to join a culture where (1) your desired behavior is the normal behavior and (2) you already have something in common with the group.

The normal behavior of the tribe often overpowers the desired behavior of the individual. Most days, we’d rather be wrong with the crowd than be right by ourselves.

The normal behavior of the tribe often overpowers the desired behavior of the individual. Most days, we’d rather be wrong with the crowd than be right by ourselves.

If a behavior can get us approval, respect, and praise, we find it attractive.

If a behavior can get us approval, respect, and praise, we find it attractive.

10

How to Find and Fix the Causes of Your Bad Habits

| I |

N LATE 2012, I was sitting in an old apartment just a few blocks from

Istanbul’s most famous street, Istiklal Caddesi. I was in the middle of a four-day trip to Turkey and my guide, Mike, was relaxing in a wornout armchair a few feet away.

Mike wasn’t really a guide. He was just a guy from Maine who had been living in Turkey for five years, but he offered to show me around while I was visiting the country and I took him up on it. On this particular night, I had been invited to dinner with him and a handful of his Turkish friends.

There were seven of us, and I was the only one who hadn’t, at some point, smoked at least one pack of cigarettes per day. I asked one of the Turks how he got started. “Friends,” he said. “It always starts with your friends. One friend smokes, then you try it.”

What was truly fascinating was that half of the people in the room had managed to quit smoking. Mike had been smoke-free for a few years at that point, and he swore up and down that he broke the habit because of a book called Allen Carr’s Easy Way to Stop Smoking.

“It frees you from the mental burden of smoking,” he said. “It tells you: ‘Stop lying to yourself. You know you don’t actually want to smoke. You know you don’t really enjoy this.’ It helps you feel like you’re not the victim anymore. You start to realize that you don’t need to smoke.”

I had never tried a cigarette, but I took a look at the book afterward out of curiosity. The author employs an interesting strategy to help smokers eliminate their cravings. He systematically reframes each cue associated with smoking and gives it a new meaning.

He says things like:

You think you are quitting something, but you’re not quitting anything because cigarettes do nothing for you.

You think you are quitting something, but you’re not quitting anything because cigarettes do nothing for you.

You think smoking is something you need to do to be social, but it’s not. You can be social without smoking at all.

You think smoking is something you need to do to be social, but it’s not. You can be social without smoking at all.

You think smoking is about relieving stress, but it’s not. Smoking does not relieve your nerves, it destroys them.

You think smoking is about relieving stress, but it’s not. Smoking does not relieve your nerves, it destroys them.

Over and over, he repeats these phrases and others like them. “Get it clearly into your mind,” he says. “You are losing nothing and you are making marvelous positive gains not only in health, energy and money but also in confidence, self-respect, freedom and, most important of all, in the length and quality of your future life.”

By the time you get to the end of the book, smoking seems like the most ridiculous thing in the world to do. And if you no longer expect smoking to bring you any benefits, you have no reason to smoke. It is an inversion of the 2nd Law of Behavior Change: make it unattractive.

Now, I know this idea might sound overly simplistic. Just change your mind and you can quit smoking. But stick with me for a minute.

WHERE CRAVINGS COME FROM

Every behavior has a surface level craving and a deeper, underlying motive. I often have a craving that goes something like this: “I want to eat tacos.” If you were to ask me why I want to eat tacos, I wouldn’t say, “Because I need food to survive.” But the truth is, somewhere deep down, I am motivated to eat tacos because I have to eat to survive. The underlying motive is to obtain food and water even if my specific craving is for a taco.

Some of our underlying motives include:*

Conserve energy

Conserve energy

Obtain food and water

Find love and reproduce

Find love and reproduce

Connect and bond with others

Win social acceptance and approval

Reduce uncertainty

Achieve status and prestige

A craving is just a specific manifestation of a deeper underlying motive. Your brain did not evolve with a desire to smoke cigarettes or to check Instagram or to play video games. At a deep level, you simply want to reduce uncertainty and relieve anxiety, to win social acceptance and approval, or to achieve status.

Look at nearly any product that is habit-forming and you’ll see that it does not create a new motivation, but rather latches onto the underlying motives of human nature.

Find love and reproduce = using Tinder

Find love and reproduce = using Tinder

Connect and bond with others = browsing Facebook

Win social acceptance and approval = posting on Instagram

Reduce uncertainty = searching on Google

Achieve status and prestige = playing video games

Your habits are modern-day solutions to ancient desires. New versions of old vices. The underlying motives behind human behavior remain the same. The specific habits we perform differ based on the period of history.

Here’s the powerful part: there are many different ways to address the same underlying motive. One person might learn to reduce stress by smoking a cigarette. Another person learns to ease their anxiety by going for a run. Your current habits are not necessarily the best way to solve the problems you face; they are just the methods you learned to use. Once you associate a solution with the problem you need to solve, you keep coming back to it.

Habits are all about associations. These associations determine whether we predict a habit to be worth repeating or not. As we covered in our discussion of the 1st Law, your brain is continually absorbing information and noticing cues in the environment. Every time you perceive a cue, your brain runs a simulation and makes a prediction about what to do in the next moment.

Cue: You notice that the stove is hot.

Prediction: If I touch it I’ll get burned, so I should avoid touching it.

Cue: You see that the traffic light turned green.

Prediction: If I step on the gas, I’ll make it safely through the intersection and get closer to my destination, so I should step on the gas.

You see a cue, categorize it based on past experience, and determine the appropriate response.

This all happens in an instant, but it plays a crucial role in your habits because every action is preceded by a prediction. Life feels reactive, but it is actually predictive. All day long, you are making your best guess of how to act given what you’ve just seen and what has worked for you in the past. You are endlessly predicting what will happen in the next moment.

Our behavior is heavily dependent on these predictions. Put another way, our behavior is heavily dependent on how we interpret the events that happen to us, not necessarily the objective reality of the events themselves. Two people can look at the same cigarette, and one feels the urge to smoke while the other is repulsed by the smell. The same cue can spark a good habit or a bad habit depending on your prediction. The cause of your habits is actually the prediction that precedes them.

These predictions lead to feelings, which is how we typically describe a craving—a feeling, a desire, an urge. Feelings and emotions transform the cues we perceive and the predictions we make into a signal that we can apply. They help explain what we are currently sensing. For instance, whether or not you realize it, you are noticing how warm or cold you feel right now. If the temperature drops by one degree, you probably won’t do anything. If the temperature drops ten degrees, however, you’ll feel cold and put on another layer of clothing. Feeling cold was the signal that prompted you to act. You have been sensing the cues the entire time, but it is only when you predict that you would be better off in a different state that you take action.

A craving is the sense that something is missing. It is the desire to change your internal state. When the temperature falls, there is a gap between what your body is currently sensing and what it wants to be sensing. This gap between your current state and your desired state provides a reason to act.

Desire is the difference between where you are now and where you want to be in the future. Even the tiniest action is tinged with the motivation to feel differently than you do in the moment. When you binge-eat or light up or browse social media, what you really want is not a potato chip or a cigarette or a bunch of likes. What you really want is to feel different.

Our feelings and emotions tell us whether to hold steady in our current state or to make a change. They help us decide the best course of action. Neurologists have discovered that when emotions and feelings are impaired, we actually lose the ability to make decisions. We have no signal of what to pursue and what to avoid. As the neuroscientist Antonio Damasio explains, “It is emotion that allows you to mark things as good, bad, or indifferent.”

To summarize, the specific cravings you feel and habits you perform are really an attempt to address your fundamental underlying motives. Whenever a habit successfully addresses a motive, you develop a craving to do it again. In time, you learn to predict that checking social media will help you feel loved or that watching YouTube will allow you to forget your fears. Habits are attractive when we associate them with positive feelings, and we can use this insight to our advantage rather than to our detriment.

Дата добавления: 2019-09-02; просмотров: 283; Мы поможем в написании вашей работы! |

Мы поможем в написании ваших работ!