Selective inference in the service of coherence

It is clear that inferences are necessary for coherence on any account of text processing. But a text can lead to an infinite number of inferences, and it is therefore important to determine just which inferences are made during reading. By far the simplest approach to this question has been made within a framework that divides inferences into those which are necessary to support the construction of a coherent representation of the text in the mind of the reader (henceforth necessary inferences) and those which are not necessary, but which are mere elaborations (henceforth elaborative inferences). The essence of the distinction is illustrated by the materialism.

(3) No longer able to control his anger, the husband threw the delicate porcelain vase against the wall. It cost him well over one hundred dollars to replace.

In this case, the inference that the vase broke is a plausible inference and must be made in order to realize an important link between the first and the second sentence. The inference is therefore necessary. Note that the inference is not necessary in the logical sense; rather, it is necessary for coherence. This of course raises the question of what is coherence. For the moment, we note that in order to link the two sentences, an explanation for the second is required, and the most plausible explanation is that the vase broke. Also, note that this inference does not need to be drawn until the second sentence is encountered.

Consider a second example.

(4) No longer able to control his anger, the husband threw the delicate porcelain vase against the wall. He had been feeling angry for weeks, but had refused to seek help.

Here, any inference that the vase broke would not be obviously useful for cohesion. Rather, the second sentence links to the previous one by providing an explanation and elaboration of it. If the inference that the vase broke had indeed been made, it would be merely elaborative. The contrast pair illustrates the distinction between forward and backward inferences. A forward inference is one which is made before the text requires it in order to establish a cohesive link. It is therefore elaborative at the time it is made. A backward inference is one which is drawn to link a previous text fragment with a later one. This distinction has been used as the foundation of an account of which inferences will and will not be made during reading; Only inferences necessary for a coherent interpretation will be made, that is, necessary inferences.

|

|

|

SEMINARV

Tasks:

1. Read the text “Second Language Acquisition” and give definitions of the terms in bold.

2. Compare the processes of first and second language acquisition.

3. Explain approaches to second language acquisition.

4. Prepare 5 more questionson the text to check the understanding of it by your groupmates.

SECOND LANGUAGE ACQUISITION*

Language teachers were once swayed by an argument that the most natural way of acquiring a second language was to emulate the process of first language acquisition. However, modern practice reflects a realisation that the two situations are very different. Compared with an infant acquiring its first language, an adolescent or adult acquiring a second:

· has less time for learning;

· is cognitively developed – possessing concepts such as causality or aspect;

· is primed by experience to seek for patterns in data and so responds to input analytically;

· already has a first language, which provides a lens through which the second is perceived;

· has access to a language of explanation, and is therefore capable of understanding (even if not applying) theoretical explanations;

· is accustomed to expressing their personality in L1, and may find their limited powers of expression in L2 a chastening experience;

· has pragmatic experience of a range of social circumstances in L1 and extensive world knowledge.

Second language acquisition: approaches

Linguistic.In the linguistic tradition, research and analysis are usually based on the assumption that the acquisition of our first language is supported by an innately acquired Universal Grammar (UG). In this context, six different positions can be adopted in relation to second language (L2) acquisition:

· The L2 learner retains access to the same UG as was available for L1.

· UG supports L1 acquisition only, and is then lost. The process of L2 acquisition is therefore very different.

· UG supports L1 acquisition only, but L2 acquisition is able to model itself upon residual traces of our experience of acquiring L1.

· UG survives until early adolescence and then decays. There is thus a critical period for second language acquisition.

|

|

|

· Universal principles are retained and continue to guide L2 acquisition. However, the user’s parameters are adjusted to L1 values and therefore need to be re-set to L2 values.

· Universal linguistic criteria (perhaps based on markedness) determine which linguistic concepts are the easiest to acquire and which are the most difficult.

One research approach is theory-driven: with researchers applying L1 linguistic theory (usually Chomskyan) to second language learning and use. Researchers often ask subjects to make L2 grammaticality judgements, which are said to tap in to their competence. A second approach is observational, with researchers obtaining longitudinal evidence of the order in which particular areas of L2 syntax are acquired and the variants which the learner employs at different stages. The data is then compared with patterns of L1 acquisition and interpreted in a framework of grammatical theory and of concepts such as parameter-switching.

Cognitive. A theoretical assumption is adopted that language is part of general cognition. It is therefore valid to trace parallels between the techniques adopted by a second language learner and those employed in acquiring other types of expertise. Cognitivist accounts of second language acquisition (SLA) cover both acquisition (how learners construct a representation of L2) and use (how they employ their knowledge of L2 in order to communicate).

There has been discussion of the relationship between explicit knowledge gained in the form of L2 instruction and implicit knowledge gained by acquisition in an L2 environment. The former is likely to provide linguistic information in an analysed form, while linguistic information that is acquired naturalistically is often in the form of unanalyzed chunks. A similar contrast exists between circumstances where accuracy is a requirement and the use of L2 may therefore be subject to careful control– and others where fluency is called for and it is desirable to aim for a high degree of automaticity.

If linguistic information is initially acquired in explicit/controlled form, then it has to be reshaped in order to support spontaneous spoken performance in the target language. A case has been put for treating second language acquisition as a form of skill acquisition not unlike learning to drive or becoming an expert chess player.

|

|

|

Much attention in SLA research has been given to transfer, the effect of the native language upon performance in L2. Early accounts of transfer drew upon behaviourist theory. Language use was depicted as habitual behaviour, with the habits of the first language having to be replaced by those of the second. Current models treat the issue in terms of the relative cognitive demands made by L2 as against those made by L1. These might reflect the extent to which a grammatical feature is marked in one language but not the other. Or it might reflect differences between languages in the importance attached to linguistic cues such as word order, inflection or animacy.

Another approach considers L2 acquisition in terms of the way in which the learner’s language develops. At any given stage, a learner is said to possess an interlanguage, an interim form of self-expression which is more restricted than the native-speaker target but may be internally consistent. Longitudinal studies have examined changes in interlanguage: for example, the different forms used to express the interrogative or negative. Most learners appear to proceed through similar stages; an explanation is found in the relative difficulty of the cognitive operations involved rather than in constraints imposed by UG.

Some commentators have suggested that SLA involves continual restructuring in which knowledge structures are reorganised in order to accommodate new linguistic insights. The Multi-Dimensional Model sees restructuring as part of a developmental process in which two important cognitive factors determine a learner’s performance. The first is the developmental stage that the learner has reached, development being represented as the gradual removal of limitations upon the linguistic structures that the learner is capable of forming. The second is the extent to which each individual engages in a process of simplification, reducing and over-generalising the L2 grammar so as to make it easy to handle.

|

|

|

Another line of research has concerned itself with the learner as an active participant in the learning process. A non-native speaker’s chief goal in L2 communicative contexts is to extract meaning, but the question arises of whether they also have to specifically ‘notice’ (direct attention to) the form of the words that is used in order to add to their own syntactic repertoire.

A further area of study that is relevant to psycholinguistics considers the way in which second-language learners handle communicative encounters, and the strategies they adopt in order to compensate for their incomplete knowledge of the lexis and grammar of the target language. There has been interest in the communication strategies adopted in spoken production, but rather less is known about the strategies employed in extracting meaning from written or spoken texts.

SEMINAR VI

Tasks:

1. Read the text “Bilingualism”and give definitions of the terms in bold.

2. Name types of bilingualism mentioned in the text.

3. Present the hypotheses of bilingual acquisition.

4. Speak about three aspects of bilingualism that Psycholinguistics takes into account.

5. Prepare 5 more questionson the text to check the understanding of it by your groupmates.

BILINGUALISM*

Bilingualism is the ‘habitual, fluent, correct and accent-free use of two languages’ (Paradis, 1986) – or of more than two languages. However, on this definition, few individuals qualify as complete bilinguals. It often happens that a bilingual is not equally competent in different aspects of the two languages: they might, for example, have a more restricted vocabulary in one than in the other or might exhibit different abilities in respect of speaking, listening, reading and writing. Furthermore, many bilinguals use their languages in ways that are domain-specific: one language might be used in the family and one reserved for educational contexts.

An early account of bilingualism (Weinreich, 1968) proposed three types. In compound bilingualism, conditions in infancy are equally favourable for both languages, and words in both are attached to one central set of real-world concepts. Co-ordinate bilingualism occurs when conditions in infancy favour one language over the other; the consequence is that the infant develops two independent lexical systems, though meanings overlap. Subordinate bilingualism occurs when the second language is acquired some time after the first, and so remains dependent upon it.

These categories have proved difficult to substantiate. However, the stage at which the two languages are acquired remains an important consideration in recent accounts, which often distinguish simultaneous bilingualism (both languages acquired concurrently), early successive or sequential bilingualism (both languages acquired in childhood but one preceding the other) and late bilingualism (the second language acquired after childhood).

Simultaneous bilingualism arises during ‘primary language development’, which commentators regard variously as occurring during the first three or the first five years of life. Exposed to two languages, infants initially mix vocabulary and syntax from both. In naming objects and actions, they often adopt the first word they encounter, regardless of which language it comes from; though in their morphology they may exhibit a preference for the less complex of their languages.

The unitary language hypothesis concludes that these infants start out with undifferentiated language systems. They begin to distinguish between the two sets of data by restricting each language to particular interlocutors, situations or pragmatic intentions. At the next stage of development, the infant distributes its vocabulary between two separate lexical systems, and becomes capable of translating words from one language to the other. However, the same syntactic rules are usually applied to both systems. In a final stage, the languages become differentiated syntactically, and mixing declines.

An alternative separate development hypothesis maintains that the two languages are distinguished from the start by the infant and that the phenomenon of mixing simply shows two incomplete systems operating in parallel.

Simultaneous bilingual acquisition appears to follow a very similar path to monolingual acquisition. There is no evidence that the acquisition process is delayed when more than one language is involved, though early vocabulary levels may be slightly lower in bilingual children. Nor do similarities between the two target languages appear to assist acquisition: an English-French bilingual does not develop language faster than an English-Chinese one.

In successive bilingualism, there is much greater variation between individuals. The time of acquisition of the second language (during the primary period/before puberty/in adulthood) may be a factor; while mastery of the later language may be limited to certain domains. In some cases, the acquisition of the later language is additive, resulting in the use of two systems in parallel. In others, the effect may be subtractive, with the later language replacing the first in some, many or all domains. The acquisition of a second language by an immigrant may even lead to the attrition of the original language if the speaker has to communicate mainly or exclusively with members of the host community.

A distinction is made between adult bilinguals who are balanced and those for whom one language is dominant. A balanced bilingual has been represented (Thiery, 1978) as somebody who is accepted as a native speaker in two linguistic communities at roughly the same social level, has learnt both languages before puberty and has made an active effort to maintain both of them. Fully balanced bilinguals are said to be rare.

Bilinguals may not always be aware of which language is their dominant one, and it has not proved easy to establish dominance. One approach has been to ask individuals which language they are conscious of having spoken first; though many recall acquiring both simultaneously. Another is to ask individuals to express a preference for one of their languages. There may be a relationship between dominance and anxiety, with the dominant language resorted to in times of stress or tiredness. Experimental methods to determine dominance have included rating bilinguals’ language skills across languages, self-rating questionnaires, fluency tests, tests of flexibility (checking the ability to produce synonyms or draw upon a range of senses for a particular word), and dominance tests where bilinguals read aloud cognates which could be from either of their languages. Even where dominance is established, the situation may not remain constant: the relationship between languages may shift as the individual’s linguistic needs and circumstances change.

Psycholinguistic research has especially considered three aspects of bilingualism:

· Storage. Are the two languages stored separately in the user’s mind or together? Possible evidence for separate stores comes from the phenomenon of code-switching where, often prompted by a change of topic, bilinguals shift with ease between their languages. However, it has been noted that code-switching takes place almost exclusively at important syntactic boundaries (the ends of clauses, phrases, sentences) and that these boundaries are often common to both languages.

· Cross-linguistic influence. Is performance in one language affected by the user’s knowledge of the other? Constituents from one language are sometimes introduced into an utterance involving the other in an effect called code-mixing. The transfer can occur at many different linguistic levels: phonological, orthographic, morphological, semantic and phrasal, and can involve structural features such as word order. Cross-linguistic lexical influence is seen in borrowing, where a word is transferred from one language to the other with its pronunciation and morphology adjusted accordingly.

· Costs and benefits. Does being bilingual have positive or negative consequences? The consequences might be linguistic, educational, cultural, affective or cognitive. In terms of linguistic development, a balance theory suggests that the possession of two languages makes increased demands on working memory, and thus leads to some decrement in proficiency in at least one of the languages. There has been little evidence to support this. An alternative view is that there is a language-independent ‘common underlying proficiency’ which controls operations in both languages. Early studies in bilingual contexts such as Wales led to the conclusion that bilingualism had an adverse effect on educational development; but these are now generally discredited. Recent research has tended to stress the positive outcomes of bilingualism: it appears that bilinguals may benefit from more flexible thought processes and from a heightened language awareness.

SEMINARVII

Tasks:

1. Read the text “How good is ‘Good Enough’?” and give definitions of the terms in bold.

2. What factors influence our language processing?

3. Give your own examples of ambiguous clauses.

4. Prepare 5 more questionson the text to check the understanding of it by your groupmates.

HOW GOOD IS “GOOD ENOUGH”?*

Previously linguists have assumed that comprehenders are trying to process the language that they hear or read as fully as possible – that they interpret each word completely and build complete syntactic structures (sometimes even more than one) when they encounter sentences. But, recent work has cast some doubt on just how complete these representations really are.

Suggestive evidence comes from the early 1980s and the Moses illusion (Erickson & Matteson, 1981), named after one of the most commonly cited sentences that exemplifies it. This illusion centers on how people initially respond when asked to say whether certain sentences are true or false, such as:

1. Moses put two of each sort of animal on the Ark

Most people, when they first encounter this sentence, answer that it is true. However, the problem is that it was not Moses, but rather Noah who put animals on the Ark. So, how do people who are fully familiar with the story of Noah and the Ark fail to notice this? Clearly, they are not paying attention to all the details of the question. Other similar effects are found when people are asked questions like, “After an air crash, where should the survivors be buried?” Barton and Sanford (1993) found that half of participants who were asked this question responded with an answer that indicated that they should be buried where their relatives wished them to be buried. These participants failed to notice that survivors are living people.

All of these cases involve some pretty complicated situations. For the Moses illusion and the survivor case, the problem hinges on not paying attention to the meaning of a particular word with respect to the bigger context. But, they also depend on trusting the assumptions of the question or statement, particularly in the survivor question: the question presupposes that survivors should be buried, and so people may sometimes be lulled into going along with this. However, the larger point that the responses to these types of sentences make is intriguing: if there are times when people are not fully processing language, when are these times? Essentially, when else are people not fully processing language?

This is not a trivial issue – until recently it was taken as established and assumed by most theories of language processing that people process language as fully as possible, in real time. The debates in language processing have really centered on what kinds of information or cues get used during processing (and when they get used), not whether people are not actually processing language fully. Thus, if it really is the case that people are not always processing language fully, but rather relying on shallow processing strategies to create “good enough” representations of what they are reading or hearing, then we will need to reconsider almost every theory of how language is processed in real time.

The researchers thus ran two further experiments using a special class of verbs that are well known to require a reflexive interpretation in that there is no object given. What does this mean? These verbs (called reflexive absolute transitive, or RAT, verbs) generally deal with actions related to personal hygiene, such as wash, bathe, shave, and dress. If someone says“Mary bathed” then we interpret the unsaid object as a reflexive (herself). So, Mary bathed means Mary bathed herself. If there is an object given, then the subject does the action on that verb: Mary bathed the baby means that Mary did not bath herself, but gave a bath to a baby. These verbs are useful here because if there is no object provided in the sentence, people should give the reflexive interpretation. So, in “While Anna dressed the baby that was small and cute spit up on the bed,” Anna dressed herself and the baby spat up. They compared these types of verbs with verbs like before, in which the object is optional, but does not have a reflexive interpretation. However, even for these RAT verbs, participants gave incorrect “yes” answers to questions like “Did Anna dress the baby” 65.6% of the time. The optionally transitive verbs were even worse–with 75% incorrect answers.

These are intriguing results – could it be that people were really not completely correcting their initial mistakes while reading?It appears so. Of course, this opens up a whole new issue – are people completely interpreting what they read the first time?

It is plausible that people may process less fully when in a challenging linguistic environment. This possibility was addressed by Ferreira (2003). She tested people’s ability to assign roles to the referents in very simple sentences. For example, if we have a sentence like “The mouse ate the cheese” we know that the mouse did the eating and it was the cheese that was eaten. In linguistic terms, the verb eat assigns two roles – an agent role (to the subject, mouse) and a theme or patient role (to the object, cheese). Ferreira tested for whether people were able to accurately assign roles in these simple sentences by having the participants listen to the sentences and then respond verbally to a prompt word that asked to them to say who/what was the “acted-on” thing in the sentence or what was the “do-er” in the sentence. So, if you heard the sentence above and then saw “Do-er” the correct answer would be for you to say “mouse.” Ferreira coded accuracy and also looked at how long it took people to respond. She was particularly interested in whether people would be less accurate for relatively simple, unambiguous sentences that nonetheless had the order of the agent/patient reversed. In the first experiment, she compared active and passive sentences. The passive version of our earlier sentence would be “The cheese was eaten by the mouse.” She also looked at sentences like these that were nonreversible (e.g., cheese cannot eat mice), sentences that were reversible but implausible if reversed, and sentences in which either referent could be the agent or patient/theme. She gave these sentences in both active and passive versions, and both active and passive tested assigning the nouns to both roles. Examples of these sentences in active and passive are as follows:

2.Nonreversible, Plausible: The mouse ate the cheese/The cheese was eaten by the mouse.

3. Nonreversible, Implausible: The cheese ate the mouse/The mouse was eaten by the cheese.

4. Reversible, Plausible: The dog bit the man/The man was bitten by the dog.

5. Reversible, Implausible: The man bit the dog/The dog was bitten by the man.

6. Symmetrical, Version 1: The woman visited the man/The man was visited by the woman.

7. Symmetrical, Version 2: The man visited the woman/The woman was visited by the man.

Ferreira found that while overall accuracy was high, as one might expect, there were still some interesting patterns in the data, as well as some conditions in particular that were surprisingly low. For all three sentence types, passives took longer to answer and were answered incorrectly more than actives.

From a certain perspective, passives are more complicated than active sentences and so perhaps it is the case that passives are more difficult simply because they are more complicated.

Ferreira argues that comprehenders do not necessary fully process language as they encounter it, but instead rely on heuristics to provide a “good enough” representation. In English, it is so often the case that the noun before the verb is the agent of the verb and that any noun following the verb is not the agent, that English speakers can simply assign agent status to the first noun.

The degree to which people bother to process language fully could be under strategic control. This does not mean that we consciously decide to process or not process fully (though it could). Instead, perhaps we only process language as fully as necessary for the needs of the current communicative situation (Ferreira, Bailey, & Ferraro, 2002).

Further evidence in support of good enough hypothesis comes from Swets, Desmet, Clifton, and Ferreira (2008), who tested specifically whether task demands could influence depth of processing. They focused on a previous finding concerning the attachment of ambiguous clauses, such as in (8):

8.The maid of the princess who scratched herself in public was terribly humiliated.

The sentence is fully ambiguous with respect to who did the scratching: it could be the maid or the princess.

Previous work (Traxler, Pickering, & Clifton, 1998; van Gompel,Pickering, & Traxler, 2001; van Gompel, Pickering, Pearson, & Liversedge, 2005) found that with sentences like these, readers actually took a shorter amount of time to read the ambiguous sentence compared with the unambiguous versions. The details of the various accounts of this effect are not important for our present purposes, but they assume, in line with accounts of other phenomena, that readers attach the ambiguous phrase to rest of the sentence when they encounter it. But, perhaps readers don’t actually do this – perhaps they do not try to interpret who scratched themselves unless they have to. Swets et al. (2008) wanted to test this hypothesis: that task demands (e.g., knowing that attachment was required or not required to correctly answer questions about the sentences) would influence whether readers actually did bother to interpret (or attach) phrases like “who scratched herself” to the maid or princess. That is, would readers underspecify the representation of the sentence if there was no reason to fully interpret it? They had people read the same sets of sentences, but for some readers all of the questions required a full interpretation of the sentence (e.g., Did the princess scratch in public?) while for other readers the questions were more superficial (e.g., Was anyone humiliated?). Swets et al. (2008) found that the pattern of reading did in fact change depending on the type of questions asked. These results suggest that readers may only interpret sentences as fully as necessary for the task, and supports the idea that we may have underspecified or “good enough” representations of language unless it is necessary to create a more detailed interpretation of a sentence.Why have “shallow” or underspecified processing? Sanford (2002) suggested that a system with finite resources should be able to allocate those resources flexibly – that is, just as in other systems (e.g., like vision) we can’t pay attention to everything all the time, and so we process fully only what we need to.

This is the information structure of a sentence and linguists have long been interested in both how languages encode information structure and how information structure interacts with meaning (Lambrecht, 1994). Recently, psycholinguists have been interested, too, in how information structure influences language processing.

Swets et al. show that task is an influence – knowing that you need to know a particular piece of information.

So we’ve seen that we process language less fullythan previously thought, but that this processing depth appearsto be dynamic – we can process language more completely whenthe task requires it, or if our attention to drawn to a particularpart of the sentence by linguistic, pragmatic, or even typographicalcues.

SEMINARVIII

Tasks:

1. Read the text “Language and the Brain”and give definitions of the terms in bold.

2. Give a light overview of brain anatomy.

3. What brain areas are especiallyimportant for language?

4. Desribe aphasias presented in the article.

5. Prepare 5 more questionson the text to check the understanding of it by your groupmates.

LANGUAGE AND THE BRAIN*

Let’s start with a quick and light overview of brain anatomy. First, the main part of the brain that is relevant for our purposes is the cerebrum or neocortex, a thin layer of tissue that forms the outermost surface of the brain. In human brains, this part has a very characteristic bumpy appearance, with lots of peaks and troughs. This part of the brain is responsible for all kinds of fundamental aspects of cognition, motor movement, and sensation. For example, the cerebrum contains primary motor cortex, which is responsible for intentional body movements, and visual cortex, which is responsible for processing information from the eyes and allowing us to recognize the identity, location, and movement of objects. The cerebrum is divided into four lobes and each of these lobes in turn has regions that are known to be important for particular functions. The most important lobes for language are the temporal lobe (near the ear) and the frontal lobe (at the front of the brain). Language function appears to be heavily dependent on certain areas within these lobes, but there are also areas deep within the brain (called subcortical areas) that are involved as well.

Further, the brain is divided into two halves, or hemispheres. These two hemispheres are not exactly mirror images of each other in terms of the functions that they support– instead many higher-level cognitive functions are lateralized, meaning that parts of the right hemisphere and left hemisphere specialize and take on functions that the other hemisphere does not.

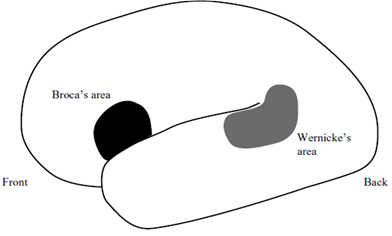

There are two areas in particular that appear to be especiallyimportant for language: an area toward the front of thebrain in the frontal lobe that includes Broca’s area and an areamore or less beneath and behind the ear toward the back of thetemporal lobe called Wernicke’s area. See Figure 1 for a schematicview of their positions in the cortex.

Figure 1Key language areas in the brain.

Classically, Broca’s area has been associated with speech production and Wernicke’s area with auditory comprehension of speech sounds. This is in part due to the constellation of impairments that appear in either the production or comprehension of language (or indeed both) when patients suffer brain damage in these particular areas. A major source of data on the organization of language in the brain comes from studying patients with aphasia, a language disorder caused by damage to the brain.

There are many kinds of aphasias, including Broca’s aphasia – which is caused by damage to Broca’s area as well as to some adjacent brain areas, particularly toward the front of the brain – and Wernicke’s aphasia, which is caused by damage to Wernicke’s area. Broca’s aphasia is characterized by difficulty with language production – with effortful, slow speech, and the striking absence of function words like prepositions, determiners, conjunctions, and grammatical inflections. So, the majority of speech in this type of aphasia is composed of nouns and verbs, produced without a fluent connection between them. Despite their often severe problems with language expression, patients with Broca’s aphasia do appear to have largely intact comprehension skills and the content that they do produce is on topic and the intended meaning is often very clear. This kind of aphasia contrasts sharply with the pattern of language loss seen when there is damage to the back of the temporal lobe (i.e., Wernicke’s aphasia).

Wernicke’s aphasia is, in many ways, the opposite of Broca’s – patients with this aphasia speak fluently and have no trouble with function words. However, the content of the speech is often not meaningful and may even contain word-like strings of sounds that are not actually words (aphasia researchers call these neologisms). Or, they may produce novel ways to refer to things, such as calling an egg “hen-fruit.” In terms of comprehension, they often show clear signs of auditory comprehension difficulties and they commonly have great difficulties repeating spoken words.

Many researches confirm that in Broca’s aphasia one key deficit is in understanding grammatical structures that involve noncanonical word ordering (sentences in which words are out of their usual order), particularly displacing grammatical or logical objects to earlier positions.

Wernicke’s aphasia has a very different pattern of deficits from Broca’s aphasia. In terms of comprehension, Wernicke’s patients generally show clearer deficits than in Broca’s aphasia, with many patients showing signs of difficulty in understanding even very straightforward sentences with all words in their usual places.

Broca’s and Wernicke’s aphasia are not the only types of aphasia. In fact there are several others, including resulting deficits from damage to the connection between Broca’s and Wernicke’s areas (i.e., conduction aphasias) as well as damage to connections to association areas from these areas (i.e., transcortical aphasias). Disordered language also arises not only from acute brain injuries but also from degenerative brain disorders like Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal dementia. One specific form of frontotemporal dementia is semantic dementia (SD). As the name suggests, the key deficit in this disorder is a progressive decrease in functioning semantic knowledge (Snowden, Goulding, & Neary, 1989). This manifests initially as having difficulties in dealing with the meanings of words –both in production and comprehension contexts. For example, patients will often produce what are called semantic “paraphasias” when they are asked to name pictures, in which they provide a (somewhat) related word instead of the intended or target word (such as calling an apple a “ball”). Indeed, naming difficulties are a key feature of SD and have been shown to reflect a deteriorating system of semantic knowledge – in particular, there is evidence that as SD progresses, patients lose knowledge that allows them to specify between similar concepts – so that a cat and an elephant may both be simply “animal” (Reilly & Peelle, 2008).

At the same time, patients with SD may produce fairly fluent discourse in terms of speech rate and may not even show any significant impairment to a casual observer under typical conversational circumstances. However, a more careful look at their discourse shows that, consistent with their increasing deficit in semantic knowledge, SD patients produce fewer lowfrequency words, and that this pattern gets stronger as the disease progresses. The overall level of meaningful content also declines with severity, while there is greater use of more generic terms (e.g., thing, animal) and highly frequent functional words (like “the” and “this”). On the other hand, phonology remains largely intact even until relatively advanced stages of the disease.

The fact that deficits in semantic knowledge can manifest with other deficits brings us nicely to another topic to consider when thinking about language and the brain: what other cognitive functions are important for language, and so might affect language ability when disrupted? Working memory is one such function, and it has been widely studied both in its own right as well as in the context of language processing. The other function is executive function, which is less well studied in the context of language, but has been increasingly identified as important to higher level language functions.

In general terms, working memory is a short of mental scratch pad – a space in which information is temporarily stored and operations on that information are carried out. One influential model of working memory (e.g., Baddeley, 1992) is principally composed of three parts: a visuospatial sketch pad (temporarily storing visual information), a central executive (directing attention), and a phonological loop (in which phonological information is held). In this model, the central executive and thephonological loop play a critical role in language, with the central executive involved in semantic integration and the phonological loop involved in phonological processing. This is not the only view of working memory; indeed, there are many theories about how working memory works and how it relates language.

ГЛОССАРИЙ

Ассоциативное поле (associativefield) –совокупность ассоциативных представлений, так или иначе связанных с данным словом.

Афазия (aphasia) – нарушение речи, возникающее при локальных поражениях коры левого полушария (у правшей) и представляющее собой системное расстройство различных форм речевой деятельности.

Бихевиоризм (behaviourism)– одно из ведущих направлений в американской психологии конца XIX – начала XX вв., наука о поведении. В основе бихевиоризма лежит понимание поведения человека как совокупности двигательных и вербальных реакций на воздействие внешней среды.

Вербальное мышление (verbalthinking)– вид мышления, в котором язык выступает как материальная опора для оперирования абстрактными понятиями.

Внутренняя речь (innerspeech)– важный универсальный механизм умственной деятельности человека, проявляющийся как промежуточный этап между мыслью и звучащей речью (при речепорождении) и между громкой речью и ментальным образом (при речевосприятии) и обеспечивающий переход симультанно существующей мысли в синтаксически расчлененную речь и наоборот.

Восприятие речи(speechperception) –один из сложных процессов речевой деятельности. Оно включает в себя восприятие звукового состава слова, грамматических форм, интонации и других средств языка, выражающих определенное содержание мысли.

Высказывание (utterance)– грамматически правильное повествовательное предложение, взятое вместе с выражаемым им смыслом.

Гендер (gender)– социальный пол, определяющий поведение человека в обществе и то, как это поведение воспринимается.

Гештальт-психология(Gestalt psychology)– одно из влиятельных направлений в психологии первой половиныXX в. Представители этого направления исходили из предположения, что сложные психологические феномены нельзя разложить на простые ментальные компоненты (структурализм) или цепи стимул – реакция (бихевиоризм). Они доказывали, что адекватное объяснение интеллектуального поведения требует ссылки на внутренние состояния психики и врожденные сложноорганизованные когнитивные структуры, которые формируют наш перцептивный опыт и знание о мире.

Двуязычие (bilingualism) – владение двумя языками с разной степенью совершенства, использование двух языковых систем в речевых процессах как одноязычных, так и предполагающих быстрый переход с одного языка на другой.

Декодирование(decoding) – процесс предметного опознания, совершаемый индивидом на основе анализа и синтеза воспринятой информации.

Детская речь (baby language)– особый этап онтогенетического развития речи детей дошкольного возраста.

Долговременная память (long-termmemory)– часть памяти когнитивной системы, предназначенная для длительного хранения информации.

Затекст(background)– отсылка к реальным событиям или явлениям, упоминаемым в тексте.

Знак (sign)– материальный предмет, воспроизводящий свойства, отношения некоторого другого предмета. Различают языковые и неязыковые знаки.

Значение(meaning)–смысл, то, что данное явление, понятие, предмет значит, обозначает.

Коннотативное значение(connotativemeaning)– эмоционально-оценочное дополнение к основному (денотативному и сигнификативному) значению.

Контекст(context)– законченный отрывок письменной или устной речи (текста), общий смысл которого позволяет уточнить значение входящих в него отдельных слов, предложений, и т. п.

Концепт (concept)– базовая когнитивная сущность, связывающая смысл со словом, позволяющая говорить об объекте, уровнях общности и выполняющая функцию категоризации.

Кодирование (encoding)– преобразование формы представления информации с целью ее передачи или хранения.

Невербальное мышление (nonverbalthinking) – вид мышления, включающий практическое и образное мышление.

Нейролингвистика (neurolinguistics) – междисциплинарная область исследования, которая изучает языковые процессы в мозгу человека, а также различные виды речевых расстройств.

Образ мира(theimageoftheworld) –целостная, многоуровневая система представлений человека о мире, других людях, о себе и своей деятельности.

Объект науки (objectofscience)– совокупность индивидуальных объектов, которые она изучает.

Онтогенез (ontogeny)– процесс индивидуального развития организма и его психической организации от рождения до конца жизни.

Подтекст(subtext)– скрытый, отличный от прямого значения высказывания смысл, который восстанавливается на основе контекста с учетом ситуации.

Порождение речи (speechproduction)– один из двух главных процессов речевой деятельности, который заключается в планировании и реализации речи в звуках или графических знаках; это совокупность действий перехода от речевого намерения к звучащему или письменному тексту, доступному для восприятия.

Предикативность(predicativity)–выражение языковыми средствами отношения содержания высказываемого к действительности как основа предложения.

Предмет науки (objectofscience)–абстрактная система объектов или система некоторых абстрактных объектов.

Пресуппозиция (presupposition) – те знания, которые, по мнению говорящего, известны слушающему и являются условием успешного понимания высказывания.

Проекция текста (textprojection)–продукт процесса смыслового восприятия текста реципиентом, в той или иной мере приближающийся к авторскому варианту проекции текста

Психолингвистика (psycholinguistics)– наука, описывающая и объясняющая функционирование языка как психического феномена при обязательном включении индивида в социокультурное взаимодействие.

Речевая деятельность– активный когнитивно-языковой процесс порождения и восприятия речи, который реализуется посредством исполнения интеллектуальных процедур.

Речь (parole) – реализация языка в триадеСоссюра язык – речь – речевая деятельность.

Семантика(semantics)–раздел лингвистики, изучающий смысловое значение единиц языка.

Семантическое расстояние(semanticdifference)–степень сходства между словами, ко торые имеют схожее значение.

Смысл(sense)–внутреннее, логическое содержание (слова, речи, явления), постигаемое разумом.

Текст(text)– законченное, целостное в содержательном и структурном отношении речевое произведение: продукт порождения (производства) речи, отчужденный от субъекта речи (говорящего) и, в свою очередь, являющийся основным объектом ее восприятия и понимания.

Трансформационная грамматика(transformativegrammar)– одна из теорий описания естественного языка, основанная на предположении, что весь диапазон предложений любого языка может быть описан путем осуществления определенных изменений, или трансформаций, над неким набором базовых предложений.

Эксперимент(experiment)– метод познания, при помощи крого в контролируемых и управляемых условиях исследуются явления действительности.

Язык (languevs. рarole) – система единиц и правил их комбинирования.

Языковая система(languagesystem) – множество элементов языка, связанных друг с другом теми или иными отношениями, образующее определенное единство и целостность.

Языковой материал(languagematerial) – все тексты, написанные на данном языке и продолжающие существовать в этом языке.

Языковое сознание(languageconsciousness) – особенности культуры и общественной жизни данного человеческого коллектива, определявшие его психическое своеобразие и отразившиеся в специфических чертах данного языка.

ПРИМЕРНАЯ ТЕМАТИКА РЕФЕРАТОВ

1. Л.С. Выготский – основоположник отечественной психо-лингвистики.

2. «Человечение языка» в концепции И.А. Бодуэна де Куртенэ.

3. Антропоцентрическая программа лингвистики В. фон Гумбольдта.

4. Предпосылки для возникновения психолингвистики в работах отечественных ученых.

5. Особенности становления и развития психолингвистики в разных странах в 50–60-х гг.

6. Современные направления психолингвистики.

7. Психологическая теория деятельности (А.Н.Леонтьев).

8. Языковое сознание и речевое мышление.

9. Знак в речевой деятельности: когнитивное vs. дискурсивное.

10. Моделирование процессов порождения и восприятия речи.

11. Проблемы онтогенеза речи в учении Ж. Пиаже и Л.С. Выготского.

12. Психосемантические проблемы значения.

13. Психолингвистические методы исследования ментального лексикона.

14. Механизмы опознавания слов и поиска их в памяти.

15. Экспериментальное изучение лексики.

16. Психолингвистический аспект текста.

17. Языковые правила и их усвоение детьми.

18. Смешные детские слова и причины их появления.

19. «Нянькин» язык – речь взрослых, разговаривающих с детьми.

20. Типы оговорок в устной речи.

21. Психолингвистические особенности рекламных текстов.

22. Психолингвистические особенности политических текстов.

23. Проявление культурных различий в ассоциативном эксперименте.

24. Теория языковой личности.

25. Подъязык субкультур (хиппи, панки, новые русские и др.).

26. Перевод как вид речевой деятельности.

27. Виды переводческих трансформаций.

28. Ошибки в речи иностранцев.

29. Мужской и женский язык в разговорной речи.

30. Языковые средства описания эмоций и психических состояний.

31. Ложь в речи и способы ее распознавания.

32. Идентификация личности по речи.

33. Способы речевого воздействия и манипуляции.

ПРИМЕРНЫЙ ПЕРЕЧЕНЬ ВОПРОСОВ

К ЗАЧЕТУ И ЭКЗАМЕНУ

1. Психолингвистика как один из возможных ваpиантов теоpетического языкознания.

2. Основные проблемы психолингвистики.

3. Источники психолингвистической мысли до оформления психолингвистики в самостоятельную науку.

4. Основные периоды в истории становления психолингвистики.

5. Аспекты языковых явлений, которые представляют интерес для лингвистики, психолингвистики и психологии.

6. Язык, речь, речевая деятельность.

7. Языковая картина мира. Соотношение категорий языкового сознания и речевого мышления.

8. Особенности процесса овладения значением слова у ребенка.

9. Общие закономерности производства и восприятия речи.

10. Роль эксперимента в психолингвистике.

11. Методы экспериментального исследования, применяемые в психолингвистике

12. Текст как объект психолингвистики.

13. Основные проблемы этнопсихолингвистики.

14. Теория лакун. Способы заполнения лакун.

15. Особенности овладения лексикой неродного языка в условиях учебного двуязычия.

16. Естественный и искусственный билингвизм. Рецептивный, репродуктивный и продуктивный билингвизм.

17. Ошибки при изучении иностранного языка, понятие интерференции.

18. Культурный шок. Лингвистический шок.

19. Сферы применения результатов психолингвистических исследований.

20. Язык и гендер. Основные особенности речевого стиля мужчин и женщин.

ЛИТЕРАТУРА

1. Белянин, В.П. Психолингвистика / В.П. Белянин. – М. : Флинта: Московский психолого-соц. ин-т, 2003. – 232 с.

2. Василевич, А.П. Исследование лексики в психолингвистическом эксперименте / А.П. Василевич. – М. : Наука, 1987. – 140 с.

3. Вежбицкая, А. Язык. Культура. Познание / А. Вежбицкая. – М. : Русские словари, 1996. – 412 с.

4. Выготский, Л.С. Мышление и речь / Л.С. Выготский. – М. : Лабиринт, 1999. – 352 с.

5. Глухов, В.П. Основы психолингвистики : учеб. пособие для студентов педвузов / В.П. Глухов. – М. : ACT: Астрель, 2005. – 351 с.

6. Глухов В., Ковшиков В. Психолингвистика. Теория речевой деятельности. М. : Изд-во АСТ, 2007. – 318 с.

7. Гумбольдт, В. фон. Избранные труды по языкознанию / В. фон Гумбольдт. – М. : Прогресс, 1984. – 400 с.

8. Красных, В.В.Основы психолингвистики и теории коммуникации. Лекционный курс / В.В. Красных. – М. : Гнозис, 2001. – 270 с.

9. Леонтьев, А.А. Основы психолингвистики / А.А. Леонтьев. – СПб : Смысл, 2003. – 285 с.

10. Лурия, А.Р. Язык и сознание / А.Р. Лурия. – М. : Изд-во Московского университета, 1979. – 309 с.

11. Петренко, В.Ф. Основы психосемантики / В.Ф. Петренко.–СПб. : Питер, 1997. – 480 с.

12. Потапов, В.В. Попытки пересмотра гендерного признака в английском языке / В.В. Потапов // Гендер как интрига познания: сборник статей.– М. : Рудомино, 2000. – С. 78–86.

13. Фрумкина, Р.М. Психолингвистика / Р.М. Фрумкина. – М. : ACADEMIA, 2001. – 316 с.

14. Хомский, Н. Язык и мышление / Н. Хомский. – М. : Изд. МГУ, 1972 – 123 с.

15. Cowles, H. Wind Psycholinguistics 101 / H. Wind Cowles. – New York : Springer Publishing Company, LLC, 2011. – 199 p.

16. Fernández, Eva M. Fundamentals of Psycholinguistics / Eva M. Fernández, H.S. Cairns. – Singapore : A John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., Publication, 2011. – 316 p.

17. Field, J. Psycholinguistics. The Key Concepts / John Field. – London : Routledge, 2004. – 366 p.

18. Handbook of Psycholinguistics. – San Diego : Academic Press Inc., 1994. – 1174 p.

19. Warren, P. Introducing Psycholinguistics / Paul Warren. – Cambridge : Cambridge University Press, 2013. – 273 p.

СОДЕРЖАНИЕ

Предисловие........................................................................................... 4

Примерный тематический план......................................................... 5

Лекционный материал......................................................................... 8

1. Психолингвистика как наука о речевой деятельности.............. 8

2. История возникновения и развития психолингвистики.......... 13

3. Психологизм языкознания....................................................... 17

4. Психолингвистический анализ процессов порождения

и восприятия речи................................................................................. 21

5. Методы психолингвистических исследований........................ 25

6. Текст как объект психолингвистики........................................ 37

7. Проблемы этнопсихолингвистики........................................... 42

8. Прикладные аспекты психолингвистики................................. 47

Задания к семинарским занятиям.................................................... 52

СеминарITheSpeaker: ProducingSpeech........................................ 52

Семинар IIThe Hearer: Speech Perception and Lexical Access....... 56

СеминарIIIFirst Language Acquisition........................................... 60

СеминарIVSelective Processing in Text Understanding................. 63

СеминарVSecond Language Acquisition........................................ 66

СеминарVIBilingualism.................................................................. 69

СеминарVIIHow good is ‘Good Enough’?.................................... 72

СеминарVIIILanguage and the Brain............................................. 76

Глоссарий............................................................................................. 80

Примерная тематика рефератов....................................................... 84

Примерный перечень вопросов к зачету и экзамену..................... 85

Литература........................................................................................... 86

*Для специальности «Современные иностранные (английский, немецкий) языки (преподавание) со специализацией Компьютерная лингвистика» предусмотрено 2 часа семинарских занятий на изучение данной темы.

*Использован материал из книги [6, с. 43–47].

*Использован материал из книги [6, с. 20–23].

*Использован материал из книги [5, с. 151–154].

*Использован материал из книги [1, с. 64–67].

* Использован материал из книги [1, с. 126–147].

*Использован материал из книги [10, с. 235–251].

*Использован материал из книги [10, с. 162–167].

*Использован материал из книги [12, с. 78–86].

*Использован материал из книги [16, с. 134–151].

*Использован материал из книги [16, с. 188–192].

*Использован материал из книги [17, с. 143–146].

*Использован материал из книги [18, с. 699–702].

*Использован материал из книги [17, с. 256–259].

*Использован материал из книги [17, с. 31–35].

*Использован материал из книги [15, с. 175–184].

*Использован материал из книги [15, с. 94–102].

Дата добавления: 2018-06-01; просмотров: 325; Мы поможем в написании вашей работы! |

Мы поможем в написании ваших работ!