ЗАДАНИЯ К СЕМИНАРСКИМ ЗАНЯТИЯМ

SEMINARI

Tasks:

1. Readthetext “TheSpeaker: ProducingSpeech” andmakeaplanofit.

2. What factors influence the speed of conversational speech?

3. Prepare 5 more questionson the text to check the understanding of it by your groupmates.

4. Study the diagram. Make sure you can explain the process of producing a sentence.

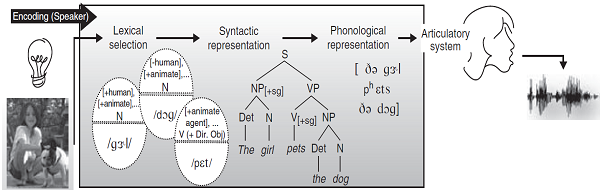

Figure 1. Diagram of some processing operations, ordered left to right, performed by the speaker when producing the sentence The girl pets the dog.

THE SPEAKER: PRODUCING SPEECH*

The processes that underlie the production and comprehension of speech are information processing activities. The speaker’s job is to encode an idea into an utterance. The utterance carries information the hearer will use to decode the speech signal, by building the linguistic representations that will lead to recovering the intended message.

Encoding and decoding are essentially mirror images of one another. The speaker, on the one hand, knows what she intends to say; her task is to formulate the message into a set of words with a structural organization appropriate to convey that meaning, then to transform the structured message into intelligible speech. The hearer, on the other hand, must reconstruct the intended meaning from the speech produced by the speaker, starting with the information available in the signal.

A Model for Language Production

The production of a sentence begins with the speaker’s intention to communicate an idea or some item of information. This has been referred to by Levelt (1989) as a preverbal message, because at this point the idea has not yet been cast into a linguistic form. Turning an idea into a linguistic representation involves mental operations that require consulting both the lexicon and the grammar shared by the speaker and hearer. Eventually, the mental representation must be transformed into a speech signal that will be produced fluently, at an appropriate rate, with a suitable prosody. There are a number of steps to this process, each associated with a distinct type of linguistic analysis and each carrying its own particular type of information. Figure 1 summarizes, from left to right, the processing operations performed by the speaker.

Production begins with an idea for a message (the light bulb on the far left) triggering a process of lexical selection. The capsule-like figures represent lexical items for the words girl, dog, and pet, activated based on the intended meaning for the message; these include basic lexical semantic and morphosyntactic information (top half) and phonological form information (bottom half). The tree diagram in the center represents the sentence’s syntactic form. The phonetic transcription to the right represents the sentence’s eventual phonological form, sent on to the articulatory system, which produces the corresponding speech signal.

|

|

|

The different representations are accessed and built very rapidly and with some degree of overlap.

The first step is to create a representation of a sentence meaning that will convey the speaker’s intended message. This semantic representation triggers a lexical search for the words that can convey this meaning. (In Figure 1, the words girl, dog, and pet are activated.) The meaning of a sentence is a function of both its words and their structural organization (The girl pets the dog does not mean the same thing as The dog pets the girl), so another encoding stage involves assigning syntactic structure to the words retrieved from the lexicon. This process places the words into hierarchically organized constituents.

Morphosyntactic rules add morphemes to satisfy grammatical requirements – for example, the requirement that a verb and its subject must agree in number. A phonological representation can then be created, “spelling out” the words as phonemes. Phonological and morphophonological rules then apply to produce a final string of phonological elements.

This phonological representation will specify the way the sentence is to be uttered, including its prosodic characteristics. The final representation incorporates all the phonetic detail necessary for the actual production of the sentence. In this representation phonological segments are arranged in a linear sequence, one after the other, as if they were waiting in the wings of a theater preparing to enter the stage.

This representation is translated into instructions to the vocal apparatus from the motor control areas of the brain, and then neural signals are sent out to the muscles of the lips, tongue, larynx, mandible, and respiratory system to produce the actual speech signal.

|

|

|

Accessing the lexicon

As mentioned above, the process of language production begins with an idea that is encoded into a semantic representation. This sets in motion a process called lexical retrieval. Remember that the lexicon is a dictionary of all the words a speaker knows. A lexical entry carries information about the meaning of the word, its grammatical class, the syntactic structures into which it can enter, and the sounds it contains (its phonemic representation). A word can be retrieved using two different kinds of information: meaning or sound. The speaker retrieves words based on the meaning to be communicated and has the task of selecting a word that will be appropriate for the desired message. The word must also be of the appropriate grammatical class (noun, verb, etc.) and must be compatible with the structure that is being constructed.

It is most certainly not the case that the structure is constructed before the words are selected, nor are all the words selected before the structure is constructed. In fact, the words and the structure are so closely related that the two processes take place practically simultaneously. Ultimately, the speaker must retrieve a lexical item that will convey the correct meaning and fit the intended structure.

This means that a speaker must enter the lexicon via information about meaning, grammatical class, and structure, only later to retrieve the phonological form of the required word. The hearer’s task, which will be discussed in detail in the next chapter, is the mirror image of the speaker’s. The hearer must process information about the sound of the word and enter his lexicon to discover its form class, structural requirements, and meaning.

Important psycholinguistic questions concern the organization of the lexicon and how it is accessed for both production and comprehension. The speed of conversational speech varies by many factors, including age (younger people speak faster than older people), sex (men speak faster than women), nativeness (native speakers are faster than second language speakers), topic (familiar topics are talked about faster than unfamiliar ones), and utterance length (longer utterances have shorter segment durations than shorter ones); on average, though, people produce 100 to 300 words per minute (Yuan, Liberman, and Cieri 2006), which, at the slower end, is between 1 and 5 words (or 10 to 15 phonetic elements) per second. (Notice that this includes the time it takes to build syntactic and phonological representations and to move the articulators, not just time actually spent in lexical retrieval.) Clearly, the process of accessing words is extremely rapid.

|

|

|

Levelt (1989) refers to the creation of sentence structure during sentence planning as grammatical encoding. For this the speaker must consult the internalized grammar to construct structures that will convey the intended meaning.

Building complex structure

A major goal of grammatical encoding is to create a syntactic structure that will convey the meaning the speaker intends. This requires accessing the speaker’s grammar.

The phenomenon of syntactic priming provides further insight into the mechanisms of production planning. Bock (1986) and Bock and Griffin (2000) described an effect they referred to as syntactic persistence, by which a particular sentence form has a higher probability of occurrence if the speaker has recently heard a sentence of that form. For example, if you call your local supermarket and ask What time do you close?, the answer is likely to be something like Seven, but if you ask At what time do you close?, the response is likely to be At seven (Levelt and Kelter 1982). Speakers (and hearers) automatically adapt themselves to the language around them, and as a consequence align their utterances interactively to those produced by their interlocutors; this process of interactive alignment has the useful consequence of simplifying both production and comprehension (Syntactic priming has been used to study a number of aspects of production.

Summary: Sentence planning

Sentence planning is the link between the idea the speaker wishes to convey and the linguistic representation that expresses that idea. It must include words organized into an appropriate syntactic structure, as sentence meaning depends upon lexical items and their structural organization. From speech errors we have evidence for the psycholinguistic representation of words and their phonological forms, the representation of morphemes, and levels of sentence planning. Experiments that elicit various types of sentences offer evidence that clauses are planning units, and that multiple factors influence the resources recruited in sentence production.

|

|

|

The sentence planning process ends with a sentence represented phonologically (at both the segmental and suprasegmental level), to which phonological and morphophonological rules have applied to create a detailed phonetic representation of the sentence, which now needs to be transformed into an actual signal, an utterance. This is the topic of the next section.

Дата добавления: 2018-06-01; просмотров: 426; Мы поможем в написании вашей работы! |

Мы поможем в написании ваших работ!