Fig 9 Coefficient of lift versus the effective angle of attack.

Typically, the lift begins to decrease at an angle of attack of about 15 degrees. The forces necessary to bend the air to such a steep angle are greater than the viscosity of the air will support, and the air begins to separate from the wing. This separation of the airflow from the top of the wing is a stall.

The wing as air "scoop"

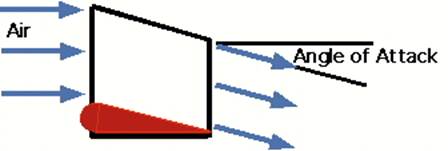

We now would like to introduce a new mental image of a wing. One is used to thinking of a wing as a thin blade that slices though the air and develops lift somewhat by magic. The new image that we would like you to adopt is that of the wing as a scoop diverting a certain amount of air from the horizontal to roughly the angle of attack, as depicted in figure 10. The scoop can be pictured as an invisible structure put on the wing at the factory. The length of the scoop is equal to the length of the wing and the height is somewhat related to the chord length (distance from the leading edge of the wing to the trailing edge). The amount of air intercepted by this scoop is proportional to the speed of the plane and the density of the air, and nothing else.

Fig 10 The wing as a scoop.

As stated before, the lift of a wing is proportional to the amount of air diverted down times the vertical velocity of that air. As a plane increases speed, the scoop diverts more air. Since the load on the wing, which is the weight of the plane, does not increase the vertical speed of the diverted air must be decreased proportionately. Thus, the angle of attack is reduced to maintain a constant lift. When the plane goes higher, the air becomes less dense so the scoop diverts less air for the same speed. Thus, to compensate the angle of attack must be increased. The concepts of this section will be used to understand lift in a way not possible with the popular explanation.

Lift requires power

When a plane passes overhead the formerly still air ends up with a downward velocity. Thus, the air is left in motion after the plane leaves. The air has been given energy. Power is energy, or work, per time. So, lift must require power. This power is supplied by the airplane’s engine (or by gravity and thermals for a sailplane).

How much power will we need to fly? The power needed for lift is the work (energy) per unit time and so is proportional to the amount of air diverted down times the velocity squared of that diverted air. We have already stated that the lift of a wing is proportional to the amount of air diverted down times the downward velocity of that air. Thus, the power needed to lift the airplane is proportional to the load (or weight) times the vertical velocity of the air. If the speed of the plane is doubled the amount of air diverted down doubles. Thus the angle of attack must be reduced to give a vertical velocity that is half the original to give the same lift. The power required for lift has been cut in half. This shows that the power required for lift becomes less as the airplane's speed increases. In fact, we have shown that this power to create lift is proportional to one over the speed of the plane.

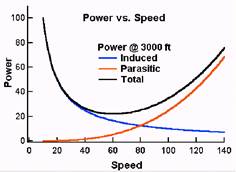

But, we all know that to go faster (in cruise) we must apply more power. So there must be more to power than the power required for lift. The power associated with lift, described above, is often called the "induced" power. Power is also needed to overcome what is called "parasitic" drag, which is the drag associated with moving the wheels, struts, antenna, etc. through the air. The energy the airplane imparts to an air molecule on impact is proportional to the speed squared. The number of molecules struck per time is proportional to the speed. Thus the parasitic power required to overcome parasitic drag increases as the speed cubed.

Figure 11 shows the power curves for induced power, parasitic power, and total power which is the sum of induced power and parasitic power. Again, the induced power goes as one over the speed and the parasitic power goes as the speed cubed. At low speed the power requirements of flight are dominated by the induced power. The slower one flies the less air is diverted and thus the angle of attack must be increased to maintain lift. Pilots practice flying on the "backside of the power curve" so that they recognize that the angle of attack and the power required to stay in the air at very low speeds are considerable.

Дата добавления: 2019-07-15; просмотров: 167; Мы поможем в написании вашей работы! |

Мы поможем в написании ваших работ!