The Kyoto Protocol: Questions and Answers

As Russia decides to back the Kyoto protocol, BBC News Online looks at the agreement which many say is the best hope for curbing the gas emissions thought partly responsible for the warming of the planet.

What is the Kyoto Protocol?The Kyoto Protocol is an international agreement setting targets for industrialised countries to cut their greenhouse gas emissions. These gases are considered at least partly responsible for global warming — the rise in global temperature which may have catastrophic consequences for life on Earth. The protocol was established in 1997, based on principles set out in a framework agreement signed in 1992.

What are the targets?Industrialised countries have committed to cut their combined emissions to 5 % below 1990 levels by 2008—2012. Each country that signed the protocol agreed to its own specific target, EU countries are expected to cut their present emissions by 8 % and Japan by 5 %. Some countries with low emissions were permitted to increase them. Russia initially wavered over signing the protocol, amid speculation that it was jockeying for more favourable terms. But the country's cabinet agreed to back Kyoto in September 2004.

Why has Russia decided to back the treaty now?The deciding factor appears to be not the economic cost, but the political benefits for Russia. In particular, there has been talk of stronger European Union support for Russia's bid to join the World Trade Organization, when it ratifies the protocol. But fears still persist in Russia that Kyoto could badly affect the country's economic growth.

Have the targets been achieved?Industrialised countries cut their overall emissions by about 3 % from 1990 to 2000. But this was largely because a sharp decrease in emissions from the collapsing economies of former Soviet countries masked an 8 % rise among rich countries. The UN says industrialised countries are now well off target for the end of the decade and predicts emissions 10 % above 1990 levels by 2010. Only four EU countries are on track to meet their own targets.

Is Kyoto in good health?Before Russia's backing, many feared Kyoto was on its last legs. But Moscow's decision has breathed new life into the protocol. The agreement stipulates that for it to become binding in international law, it must be ratified by the countries who together are responsible for at least 55 % of 1990 global greenhouse gas emissions. The treaty suffered a massive blow in 2001 when the US, responsible for about quarter of the world's emissions, pulled out. The additional uncertainty over Russia's position was seen as another nail in the coffin, but observers are now hopeful the 55 % threshold can be reached.

Why did theUS pull out?US President George W. Bush pulled out of the Kyoto Protocol in 2001, saying implementing it would gravely damage the US economy. His administration dubbed the treaty "fatally flawed", partly because it does not require developing countries to commit to emissions reductions. Mr. Bush says he backs emissions reductions through voluntary action and new energy technologies.

How much difference will Kyoto make?Most climate scientists say that the targets set in the Kyoto Protocol are merely scratching the surface of the problem. The agreement aims to reduce emissions from industrialised nations only by around 5 %, whereas the consensus among many climate scientists is that in order to avoid the worst consequences of global warming, emissions cuts in the order of 60 % across the board are needed. This has led to criticisms that the agreement is toothless, as well as being virtually obsolete without US support. But others say its failure would be a disaster as, despite its flaws, it sets out a framework for future negotiations which could take another decade to rebuild. Kyoto commitments have been signed into law in some countries and in the EU, and will stay in place regardless of the fate of the protocol itself. Without Kyoto, politicians and companies working towards climate-friendly economies would face a much rougher ride.

What about poor countries?The agreement acknowledges that developing countries contribute least to climate change but will quite likely suffer most from its effects. Many have signed it. They do not have to commit to specific targets, but have to report their emissions levels and develop national climate change mitigation programmes, China and India, potential major polluters with huge populations and growing economies, have both ratified the protocol.

What is emissions trading?Emissions trading works by allowing countries to buy and sell their agreed allowances of greenhouse gas emissions. Highly polluting countries can buy unused "credits" from those which are allowed to emit more than they actually do. After much difficult negotiation, countries are now also able to gain credits for activities which boost the environment's capacity to absorb carbon. These include tree planting and soil conservation, and can be carried out in the country itself, or by that country working in a developing country.

Are there alternatives?One approach gaining increasing support is based on the principle that an equal quota of greenhouse gas emissions should be allocated for every person on the planet. The proposal, dubbed "contraction and convergence", states that rich countries should "contract" their emissions with the aim that global emissions "converge" at equal levels based on the amount of pollution scientists think the planet can take. Although many commentators say it is not realistic, its supporters include the United Nations Environment Programme and the European Parliament.

Kyoto— the only Game in Town

Climate change is no longer a matter of argument.There is no previous time in recorded history when the world's temperature has risen so much and so quickly. Even the 400,000 year probes into the ice cap reveal no parallel. We are therefore in entirely uncharted waters. Mankind has been pouring unprecedented amounts of filth into the air ever since the beginning of the industrial revolution. We have a planet that supports vastly more people than ever before and their numbers are still growing fast. Every child has expectations significantly greater than their fathers and mothers. Those expectations, however limited they may seem to the rich, are similarly based upon increased consumption which means more greenhouse gas emissions.

Optimism.What is done can't be undone. W?e have already changed our climate significantly and there is considerably more change on the way, set in train by the gases we have already released. What we can do is to restrict the growth in that change so that we can cope with it. If we allow global warming to grow unrestrictedly, then life on the planet will become increasingly impossible as it threatens the Gulf Stream and other crucial elements that sustain the earth's benign atmosphere. Happily, the world is waking up. Just this month, American States are suing the utilities for their refusal to take global warming seriously. The Chartered Institute of Insurance is warning all its members of the present reality of climate change and its impact upon insurance risk. Optimism is rising that Russia will ratify the Kyoto Protocol so it will come into force — even without the Unites States.

Catalyst.So, why Kyoto? It isn't anything like enough. Its targets for reduction in our greenhouse gases are smaller than we need but it is the first step on the journey and that is always the hardest. Already, Kyoto has meant that one of the world's two great trading powers — the European Union — has made major changes in order to meet its targets for reduction.

The likelihood is that, by 2012 the 15 longstanding members will have cut emissions by 8 %. Given how fast emissions were rising, that is a remarkable

achievement and another example of the huge value of the EU. The decoupling of economic growth from the growth in emissions is crucial and the latest figures show that it has been done. Even without coming into force, Kyoto has been the catalyst for this change.

Rich countries.Its effect even on the US has been remarkable. American business and many of the states are responding to its challenge even though President Bush has behaved with such callous disregard. Without Kyoto, there would have been no such rallying, no widely accepted program, and no effective base upon which to build. Kyoto was a deal between the rich countries. Only then could we expect developing countries to join in the global response. After all, it was the rich world that caused the problem. Yet, already, China is developing in a much cleaner way than was forecast. The Kyoto mechanisms which reward clean technology transfer are, indeed, beginning to have some effect not least through international institutions like the World Bank.

Economic pressure.Of course, America still holds the key. With 4 % of the world's population it produces 25 % of the world's pollution. Yet, it depends on world trade and, as the rest of the world makes its investment decisions in the light of Kyoto, American businesses are losing out to European suppliers working within the Kyoto system. No wonder that it is US business that is pushing Bush to change. Of course, any US president will need a way to climb down, if he is in effect to join in. There will be some new package and a different name. But Kyoto is the only game in town and it will mould and probably save our planet's future.

UNIT 7

OIL and GAS

The oil price shocks

Oil is an important commodity in modem economies. Oil and its derivatives provide fuel for heating, transport, and machinery, and arc basic inputs for the manufacture of industrial petrochemicals and many household products ranging from plastic utensils to polyester clothing. From the beginning of this century until 1973 the use of oil Increased steadily. Over much of this period the price of oil fell in comparison -with the prices of other products. Economic activity was organized on the assumption of cheap and abundant oil.

In 1973 – 74 there was an abrupt change. The main oil-producing nations, mostly located in the Middle East but including also Venezuela and Nigeria, belong to OPEC — the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries. Recognizing that together they produced most of the world's oil, OPEC decided in 1973 to raise the price at which this oil was sold. Although higher prices encourage consumers of oil to try to economize on its use, OPEC countries correctly forecast that cutbacks in the quantity demanded would be small since most other nations were very dependent on oil and had few commodities available as potential substitutes for oil. Thus OPEC countries correctly anticipated that a substantial price increase would lead to only a small reduction in sales. It would be very profitable for OPEC members.

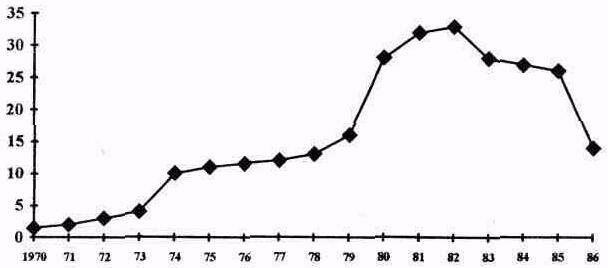

Oil prices are traditionally quoted in US dollars per barrel. Fig. 1 shows the price of oil from 1970 to 1986. Between 1973 and 1974 the price of oil tripled, from $2,90 to $9 per barrel. After a more gradual rise between 1974 and 1978 there was another sharp increase between 1978 and 1980, from $12 to $30 per barrel. The dramatic price increases of 1973 – 79 and 1980 – 82 have become known as the OPEC oil price shocks, not only because they took the rest of the world by surprise but also because of the upheaval they inflicted on the world economy, which had previously been organized on the assumption of cheap oil prices.

People usually respond to prices in this or that way. When the price of some commodity increases, consumers will try to use less of it but producers will want to sell more of it. These responses, guided by prices, are part of the process by which most Western societies determine what, how and for whom to produce.Consider first how the economy produces goods and services. When, as in the 1970s, the price of oil increases six-fold, every firm will try to reduce its use of oil-based products. Chemical firms will develop artificial substitutes for petroleum inputs to their production processes; airlines will look for more fuel-efficient aircraft; electricity will be produced from more coal-fired generators. In general, higher oil prices make the economy produce in a way that uses less oil.

Oil price ($ per barrel)

Figure 1. The price of oil. 1970 – 86

How does the oil price increase affect what is being produced? Finns and households reduce their use of oil-intensive products, which are now more expensive. Households switch to gas-fired central heating and buy smaller cars. Commuters form car-pools or move closer to the city. High prices not only choke off the demand for oil-related commodities; they also encourage consumers to purchase substitute commodities. Higher demand for these commodities bids up their price and encourages their production. Designers produce smaller cars, architects contemplate solar energy, and research laboratories develop alternatives to petroleum in chemical production. Throughout the economy, what is being produced reflects a shift away from expensive oil-using products towards less oil-intensive substitutes. The for whom question in this example has a clear answer. OPEC revenues from oil sales increased from $35 billion in 1973 to nearly $300 billion in 1980. Much of this increased revenue was spent on goods produced in the industrialized Western nations. In contrast, oil-importing nations had to give up more of their own production in exchange for the oil imports that they required. In terms of goods as a whole, the rise in oil prices raised the buying power of OPEC and reduced the buying power of oil-importing countries such as Germany and Japan. The world economy was producing more for OPEC and less for Germany and Japan. Although it is the most important single answer to the 'for whom' question, the economy is an intricate, interconnected system and a disturbance anywhere ripples throughout the entire economy,

In answering the 'what' and 'how' questions, we have seen that some activities expanded and others contracted following the oil price shocks. Expanding industries may have to pay higher wages to attract the extra labour that they require. For example, in the British economy coal miners were able to use the renewed demand for coal to secure large wage Increases. The opposite effects may have been expected if the 1986 oil price slump had persisted.

The OPEC oil price shocks example illustrates how society allocates scarce resources between competing uses.

A scarce resource is one for which the demand at a zero price would exceed the available supply. We can think of oil as having become more scarce in economic terms when its price rose.

Kazakhstan has the Caspian Sea region's largest recoverable crude oil reserves, and, according to the 2008 BP Statistical Energy Survey, had proved oil reserves of 39.828 billion barrels at the end of 2007 or 3.21 % of the world's reserves. According to the 2008 BP Statistical Energy Survey, Kazakhstan produced an average of 1490.3 thousand barrels of crude oil per day in 2007 and consumed an average of 218.53 thousand barrels of oil a day.

Kazakhstan sits near the northeast portion of the Caspian Sea and claims most of the Sea's biggest known oil fields. The Ministry of oil and gas, the Ministry of coal and power and the Ministry of geology have all been absorbed into the now operating Ministry of Energy, Industry and Trade.

KazMunaiGaz (formerly Kazakhoil) is the major player in the country's oil sector. Kazakhoil was set up in March 1997 following abolishment of the Munaigas state - owned company and its 34 subsidiaries responsible, until then, both for oil and gas. The functions of KazMunaiGaz are implemented either directly or through its participation to other companies. In most of those companies, 18 in number, KazMunaiGaz is the major shareholder with employees and/or private investors holding minority stakes.

The Tengiz field is located in the swamplands along the northeast shores of the Caspian Sea and is the largest source of oil production in the country. Existing production from this field is expected to double in the next decade. The Kashagan field, the largest oil field outside the Middle East and the fifth largest in the world (in terms of reserves), is located off the northern shore of the Caspian Sea, near the city of Atyrau. It is expected that this field will add an additional 1 million bbl/d in the next decade.

Kaztransoil is the product of two major transportation associations brought together, again during the 1997 sector restructuring. Kaztransoil, thus controls about 6300 kms of pipelines for crude oil and another 1100 kms for oil products. Its assets also include oil storage facilities, pumping stations, collection points, rail loading stations and loading piers for Caspian vessels.

According to the 2008 BP Statistical Energy Survey, Kazakhstan had 2007 proved natural gas reserves of 1.9 trillion cubic metres. The country had 2007 natural gas production of 27.25 billion cubic metres and consumption of 19.77 billion cubic metres, making it a net gas exporter.

UNIT 8

Дата добавления: 2018-02-18; просмотров: 418; Мы поможем в написании вашей работы! |

Мы поможем в написании ваших работ!