Monopredicative - Potypredicative Syntactic Units

Second, we take into consideration the volume characteristics of the predication in sentences, 'sentence representatives', and sentencoids. A distinction is drawn between monopredicative and polypredicative sentences, 'sentences representatives', and sentencoids. Monopredicative syntactic units comprise one primary predication; polypredicative syntactic units include more than one primary predication.

Declarative - Interrogative - Imperative — Exclamative Monopredicative Syntactic Units

Monopredicative sentences (and 'sentence representatives') are further classified into declarative, interrogative, imperative, and excJamative. Traditional grammar calls it a functional classification. Declarative sentences are said to make statements; interrogative sentences are said to ask questions; imperative sentences are said to make requests and give orders; exclamative sentences are said to express strong feelings. It would be well and good if it were always

234

the case. Unfortunately, it is not so. The so-called declarative sentences not only make statements but also ask questions, give orders, and express strong feelings. Cf.:

The new room is better? - Yes, sir (J. Fowles). In future you'll keep away from my wife. It's an order

(H. tines).

You're killing me! (W.C. Williams).

The so-called interrogative sentences not only ask questions but also make statements and requests and express strong feelings.

Cf.:

How can I climb that? (P.H. Mathews). <It implies / can Y

climb it.>

Will you come in? (J. Galsworthy). <It implies Come in,

please!>

Now, isn't he a terrible fellow! (J. Joyce). <It implies He is a terrible fellow!>

The so-called imperative sentences not only make requests and give orders but also make statements and express strong feelings. Cf.:

Spare the rod and spoil the child (Proverb). <It implies If you spare the rod, you will spoil the child. >

Don't be so stupid! (M. Swan). <It expresses annoyance>

Exclamative sentences comprising an emphatic do, does, did or opening with what and how seem to be monofunctional. Cf:

I never did love him! (R. Lardner).

What eyes he's got! (A.M. Burrage).

How melancholy it was! (J. Joyce).

The classification of monopredicative two-member sentences into declarative, interrogative, imperative, and exclamative was only conceived as functional. In practice, it was carried out on a structural basis, namely the order of subject and predicate in relation to each other [H. Sweet; D. Biber et al.; G.G. Potcheptsov].

|

|

|

In declarative sentences, the subject precedes the predicate, e.g.:

My mother died soon after (D. Robins).

In declarative 'sentence representatives', the subject comes before the operator standing for the predicate, e.g.:

Who'll run the business while I'm away? - I will (J. Collins).

235

In interrogative sentences and 'sentence representatives', the auxiliary part of the predicate precedes the subject. The notional part of the predicate in interrogative sentences follows the subject. In 'sentence representatives', the notional part of the predicate is never used. Cf.:

Do you have a car? (S. Sheldon),

We could get a double room. - Could we? - Oh, yeah. (K. Burke).

Where did she get my address? (J. Carey).

We can't be in the forest, anyway. — Why can't we? (S. Hill).

In imperative sentences and 'sentence representatives', there is usually no subject. Cf.:

Give me the dictionary (E.S. Gardner).

Perhaps I should fry again?- Don't (J. Osborne).

Exclamative sentences begin with what or how, followed by the word the speaker wants to emphasize, and continue with the 'subject-predicate' pattern, e.g.:

What a pleasant surprise it would have been! (P. Abrahams).

How beautifully you sing! (M. Swan).

'Sentence representatives' have no specific exclamative structure.

Since most sentencoids lack the 'subject-predicate' pattern, their classification into declarative, interrogative, imperative, and exclamative is purely functional. Cf.:

Where are you going to stay? - With my people (J. Galsworthy) - declarative sentencoid.

I've decided to write a little statement for the Echo... - The college paper? - The college paper (J. O'Hara) - interrogative sentencoid.

Home! Go home\ (J. London) - imperative sentencoid.

Last night at that banquet I thought France was saved. Such speeches! Such songs! And so many swords upraised! (U. Sinclair) — exclamative sentencoids.

Positive ~ Negative Syntactic Units

All the monopredicative syntactic units can be positive and negative. The question arises if negation can be regarded as a structural characteristic of predicative syntactic units. We think it

|

|

|

236

can, but on two conditions. First, if it denies or rejects the proposition as a whole. Second, if it has constant grammatical means of its expression. English grammarians draw a distinction between two kinds of negation: local negation and clausal negation. The scope of local negation is usually restricted to a single word that is not a verb. Cf:

No one answered him (W, Golding).

And now she had nobody to protect her (J. Joyce).

They never talk (J. Thurber).

You never talk anything but nonsense. - Nobody ever does (O. Wilde).

What happened? - Nothing (J. Collins).

In all these cases, the propositions as a whole are positive. In other words, local negation cannot be regarded as a structural characteristic of a monopredicative syntactic unit. It is lexical, not grammatical.

With clausal negation, the whole proposition is denied. Clausal negation has constant grammatical means of its expression: the negator not or its contracted form n 't is added after the operator, e.g.:

/ haven't made up my mind yet (I. Shaw).

Ann isn't a doctor (V. Evans).

Oh, that is nonsense. - It isn't (O. Wilde).

If there is no auxiliary verb and the main verb is not the copula be, the auxiliary verb do has to be inserted as dummy operator. Cf:

I know (W.S. Maugham). ~* I don't know (H.E. Bates).

You promised me.—•* I didn't promise (J.D. Salinger).

Go to sleep (J. Irving). —» Don't go to sleep (K. Mansfield).

Since sentencoids usually lack the predicate-verb, the scope of clausal negation in them is restricted to sentencoids with dependent explicit predication, e.g.:

Why hasn't he come to-night? - Because he wasn't asked (D.H. Lawrence).

As clausal negation, which is attracted to the predicate-verb, denies the proposition as a whole and has constant grammatical means of its expression, it constitutes a structural characteristic of monopredicative syntactic units. In contrast to local negation that is lexical, clausal negation is grammatical. So, positive and negative sentences, 'sentence representatives', and sentencoids with clausal

237

negation can be regarded as two different structural types of monopredicative syntactic units.

|

|

|

English monopredicative syntactic units can comprise only one negation: either clausal or local, e.g.:

She didn't reply (J. Collins) - one clausal negation.

I never heard of it (S. Sheldon) - one local negation.

In Russian monopredicative syntactic units, clausal negation can go hand in hand with several local negations. Cf.:

Nobody ever tells me anything (M. Bond) - one local negation.

HuKmo HUKOzda nunezo Mne ne paccK03bieaem, - One clausal and three local negations.

11. SENTENCE MODELS Drawbacks of the Model of Pans of the Sentence

Monopredicative two-member sentences are analyzed in terms of subject, predicate, object, attribute, adverbial, etc. The traditional model of parts of the sentence distinguishes between principal parts of the sentence (subject, predicate) and secondary parts of the sentence (object, adverbial, attribute, etc.). Secondary parts of the sentence are said to depend on principal parts. It would be well and good if the notion of dependence figured only in the opposition of principal and secondary parts. However, many linguists are of opinion that the predicate also depends on the subject. If the predicate does depend on the subject, then it is not clear why they refer it to principal, not to secondary parts of the sentence.

What is more, it is very difficult to differentiate secondary-parts of the sentence on the basis of the traditional model of parts of the sentence.

But the main drawback of the traditional model of parts of the sentence, according to G.G. Potcheptsov, lies in the fact that, although the so-called parts of the sentence are singled out on the basis of the sentence, linguists generally study them irrespective of the sentence, taking into consideration only the mutual relations of these or those parts. In other words, the study of parts of the sentence is displaced into the sphere of word combination.

Distributional Model

Since the model of parts of the sentence has a number of weak points, linguists began to look for new models. In 1914, with the publication of L. Bloomfiled's Introduction to the Study of Language, there appeared a new theory of descriptive grammar, which put on a firm basis the inductive rather than the deductive approach to language analysis. L. Bloomfield and his adherents set out to describe language as it exists, without being concerned with questions of correct and incorrect usage. In doing so, they directed their attention to the formal features of language.

|

|

|

The shift of American linguists' attention from meaning to form at the beginning of the 20 century was quite natural. In the first place, descriptive linguistics developed from the necessity of studying half-known and unknown languages of the Indian tribes. They had no writing, and therefore the first step of work was to be keen observation and rigid registration of linguistic forms. In the second place, the languages of the Indian tribes have little in common with the Indo-European languages; they are languages devoid of morphological forms of separate words. That's why descriptive linguists could not analyze sentences in traditional terms.

The generally accepted method of linguistic description became that of distribution. The distribution of an element is the sum total of all environments in which it occurs. The distribution is defined by means of substitution. Thus, Zand Fare included in the same element/* if the distribution of X is in some sense the same as the distribution of Y, e.g. the words door, window, table, bed, etc. can be included in one class with the word fire because they can occur in the same environment. Cf.:

She was sitting close to the fire (W. Faulkner),

She was sitting close to the door.

She was sitting close to the window.

She was sitting close to the table.

She was sitting close to the bed.

The distributional method is not a new idea in the history of English grammar. But traditional grammar was guided by this method only in practice, whereas structural linguistics has given

238

239

recognition to the distributional method within the theory of grammar.

One of the representatives of structural linguistics is Ch. Fries. He challenges the conventional logical approach to the grammatical analysis of a sentence, declaring that in the study of sentence structure the use of meaning is unscientific. True, Ch. Fries draws a distinction between two kinds of meaning: lexical and structural. The term 'lexical meaning' is assigned to the dictionary definitions of words; 'structural meaning' - to those signals that show grammatical function. Lexical meanings in grammar, he writes, are redundant; structural meanings are fundamental and necessary. An English sentence, in his opinion, is not a group of words as such - i.e. a group of lexical units - but rather a structural pattern made up of classes and groups of words which are properly identified by formal markers and by their position in the pattern. For instance, the English sentence Then he spoke to me (A. Maltz) has the following distributional model (DM): Then he spoke to me. 4 la 2-d F lb,

where 4 is a word of Class 4 (traditionally - an adverb); la and lb are words of Class 1 (traditionally - nouns), having different referents; 2-d is a word of Class 2 (traditionally - a verb) in a past tense form; F is a word of Group F (traditionally - a preposition).

As opposed to the traditional model of parts of the sentence, the distributional model of Ch. Fries is purely formal. So, one might be led to believe that it meets the requirements of structural sentence analysis. However, if one goes deeper into it, he will see that things are not as easy as that. Since the main structural characteristic of a sentence is the presence of predication, structural sentence analysis should deal with defining the role of sentence components in realizing predication. Ch. Fries does nothing of the kind. He regards the sentence as a linear sequence of words with no reference to their participation in the realization of predication.

The linear model can generate only the simplest sentence structures. Even this it sometimes cannot do properly as it does not indicate the groupings inside the sentence and the syntactic relations between them. No wonder that the distributional model of Ch. Fries cannot explain the difference between such sentences as:

The police shot the man in the red cap. The police shot the man in the right arm.

| A |

la 2-d A 1D F A 3 I1

According to Ch. Fries, these sentences are built on the same model (A T 2-d A lb F A 3 lc). However, even at first sight it is evident that the sentences are not identical: the first means that the police shot a man who had a red cap on; the second - that the police injured the man's right arm.

In the case of more complex sentence structures, the linear distributional model turns out ineffective. Thus, it fails to generate passive constructions, negative, interrogative, and polypredicative sentences. What is more, the linear distributional model wholly disregards the functional nature of the singled out sentence components. And it must be taken into consideration because the sentence is a communicative syntactic unit.

Model of Immediate Constituents

The model of immediate constituents (ICM) represents the sentence not as a linear sequence of words, but as a hierarchy of two-part constructions on a series of levels. The largest immediate constituents of the simple sentence The warm sun excited the little girl (J. Cheever) are the noun phrase (NP) - the warm sun and the verb phrase (VP) - excited the little girl. The boundary between mem goes between the word of Class 1 (N) - sun and the word of Class 2 (V) -excited. Each part, in turn, is subject to further analysis. The noun phrase the warm sun has two immediate constituents: the determiner the and the noun phrase warm sun. The noun phrase warm sun consists of the word of Class 1 sun and the word of Class 3 warm.

The verb phrase excited the little girl also comprises two immediate constituents: the word of Class 2 excited and the noun phrase the little girl. The noun phrase the little girl is analyzed into the determiner the and the noun phrase little girl. Finally, in the noun phrase little girl the word of Class 1 girl is separated from the word of Class 3 little.

240

241

| excited the little girl |

| he little girl little girl |

|

|

|

|

So, the above-mentioned sentence will look like this in the immediate constituents model:

The warm sun excited the little girl

| Layer 4 Layer 3 Laver 2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |||

|

| ||||||||||||

|

|

| |||||||||||

| Laver 1 |

| |||||||||||

T

the

ANP V warm sun excited

Adj N

warm sun

The ultimate constituents (UCs) of a sentence are words. Some linguists suggest that the analysis into immediate constituents should not stop on the level of words, but go on till we reach the level of morphemes. If we accepted this conception, we would be bound to say that the sentence The warm sun excited the little girl has five layers because the word of Class 2 (V) - excited is derivative and can be broken up into the root excit- and the suffix -ed.

However, as R.S. Wells rightly points out, the immediate constituents of such a syntactic unit as a sentence should be independent of each other in their distribution, and bound morphemes lack syntactic independence.

The immediate constituents model helps not only analyze but also generate sentences. The generation of a sentence can be represented in the form of a 'derivation tree'. The derivation tree is drawn as two branches forking out from the sign S (sentence). Each branch has nodes in it from which smaller branches fork out. Each node corresponds to a phrase; the two forking branches correspond to the immediate constituents of the phrase. In other words, the generation of a sentence first involves classes and groups of words. Concrete lexical elements are chosen on the lowest level. The generation of a sentence always proceeds with the change of one element at the application of each rule.

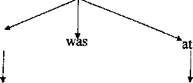

The diagram below is a derivation tree for generating simple sentences with a transitive verb:

Fig. 2.

The immediate constituents model is more powerful than the distributional model. It has certain advantages both in analyzing and generating sentences because it indicates the groupings of the immediate constituents and the order in which the generation of a sentence must proceed.

At the same time, it is not devoid of drawbacks either. Just like the distributional model, the immediate constituents model fails to elucidate the role of ultimate constituents in realizing predication. At first sight, the largest immediate constituents of a sentence - the noun phrase and the verb phrase - represent the nominal and the verbal components of predication respectively. On closer inspection, it becomes evident that the notions of 'noun phrase' and 'verb phrase' are much wider, for in addition to the nominal and verbal components proper they comprise various modifiers. In other words, the immediate constituents model does not draw a distinction between the predicative basis of a sentence and its expansion, to say nothing of differentiating the expansion according to its modifying the predication as a whole or part of it.

The model of immediate constituents has a limited sphere of application: it deals only with isolated simple sentences. The nature of polypredicative sentences and the interrelations between active -passive, declarative - interrogative, and affirmative - negative constructions remain obscure.

But even the analysis of isolated simple sentences in the immediate constituents model leaves much to be desired. First, it

242

243

| 2) structurally identical but semantically different units of the |

does not answer the question how to treat homogeneous parts. Some linguists look upon them as constituting one immediate constituent. Others are of opinion that homogeneous parts should be further subdivided. Second, it fails to solve the problem of function words (prepositions, conjunctions, etc.). Some single them out into a separate immediate constituent; others treat them together with this or that notional word.

And last but not least, studying isolated sentences and underestimating the criterion of semantics, the immediate constituents model appears ineffective in bringing to the fore the points of difference between:

1) free and phraseological units, e.g. He showed the white feather (A.B. kvhhh) both as a phraseological unit and as a free word combination has the same tree:

He showed the white feather

| He |

showed the white feather

| showed |

the white feather

| the" |

| Fig. 3. |

white feather

white feather

| John is eager to please John is easy to please (N.F. Irtenyeva) |

|

|

type:

| John |

|

|

is eagerJea§y) to please

is eaggr (easy) to

eager (easy) to please

is

Fig. 4.

According to the model of immediate constituents, these sentences are identical. But they are different. In the first sentence, 'John is eager to please', John is the agent: he is eager to please somebody. In the second sentence, 'John is easy to please', John is not the agent, but the recipient of the action: it is easy for people to please John.

Dependency Tree

Dependency grammar (DG) also presents the generation of a sentence in the form of a sentence tree, but the dependency tree (DT) is constructed on a different principle from the derivation tree in immediate constituents grammar. The derivation tree does not draw a distinction between governors and dependents. In the dependency tree, according to D.G. Hayes, the relation between every pair of minimal syntactic units, by which words are meant, is that of direct dependency. Cf.:

244

245

ICG

DG

/ talked to Jo (W. Trevor) I _______ - ------------ talked

large glasses (L.E. Reeve)

large glasses (L.E. Reeve)

to

The establishment of certain hierarchies inside the sentence is, no doubt, a considerable contribution of dependency grammar to the theory of linguistics.

The thing that raises doubts here is the validity of regarding the verb as the only root of all dependency trees, e.g.:

Jack spoke loudly (W. Golding) spoke

Jo

Fig. 7.

One-member imperative sentences have one root, e.g.: Put the thing on the table (J.R. Baker) put

Jack

loudly

•^

thing

1

the

The verb does play an important role in realizing predication, the main structural characteristic of the sentence, because the predicative meanings of modality and tense find their expression in the verb.

But in addition to modality and tense, predication comprises person characteristics. In inflected languages, the verb admits of person distinctions. So, in inflected languages the verb can be looked upon as syntactically central unit. In analytical English, things are different. It would not be an exaggeration to say that the English verb lacks person characteristics (the only exception in the domain of regular verbs is the inflection -s of the third person singular in the sphere of the present tense). In analytical languages, person characteristics generally find their expression in the nominal component of predication, i.e. in analytical languages there are usually two syntactically central units, and dependency trees in them should have two roots: nominal and verbal, e.g.:

246

the

Fig. 8.

Then, there arises the problem of the nature of the verbal root. The representatives of dependency grammar think that the verbal root is constituted by the notional verb, e.g.:

247

| table |

One morning a new man -was sitting at this table (J. Collier)

------------------- sitting

|

|

|

|

| new |

| morning |

| one |

man-

table

One morning a new man was sitting at this table (J. Collier)

----------------- wasjiitting

|

|

|

|

| new |

| a mornin |

| one |

man-

I this

this

Fig. 9.

It really is, when we deal with a synthetic form of the verb (see Fig. 6,7,8), But when the predicate-verb is in an analytical form, all the predicative categories (modality, tense, and sometimes person) are rendered by the auxiliary verb. In this case, we are hardly justified in restricting the verbal root of the dependency tree to the notional verb. The conception of the French scholar L. Tesniere, who widens the notion of the verbal root by including into it the predicate-verb as a whole, seems more convincing. Cf:

Fig. 10.

Don't be cross with your sweetheart (F.S. Fitzgerald)

don't be cross

with

1

sweetheart

^r

your

Fig. 11.

248

249

The merit of the dependency tree lies in the fact that it defines the most important sentence element. However, it fails to elucidate the role of other sentence components in realizing predication because it wholly disregards the functional criterion indispensable for the analysis of such a communicative phenomenon as the sentence. The singled out minimal syntactic units do build up a hierarchy of several levels, but the levels are formal and hence -functionally heterogeneous. Thus, in Fig. 6, the second level includes such heterogeneous units as the nominal component of predication Jack and the adverbial loudly, which modifies the verbal component of predication spoke.

Transformational Model

As opposed to the distributional model, the immediate constituents model, and the dependency tree, which deal with isolated sentences, the transformational model (TM) of Z.S. Harris and N. Chomsky discloses the existing relations between various sentence types (e.g. positive - negative, declarative - interrogative, etc.). Transformational analysis begins with the assumption that certain sentences are basic or kernel and other sentences are derived from them by means of transformational rules. The fundamental aim in the linguistic analysis of a language is to find a set of transformational rules (that make up the grammar of the language) by which all the grammatical, and only grammatical, sentences of the language can be generated.

But what are the criteria for determining what is grammatical and what is not? The notion 'grammatical', writes P.A. Gaeng, cannot be identified with 'meaningful' because a grammatical sentence can be meaningless, e.g.:

Oysters living on the moon don't whistle (P.A. Gaeng).

'Grammatical', surely, is not a synonym of'authentic', since a grammatical sentence can be a lie, e.g.:

My grandfather was President of the United States.

250

'Grammatical' does not mean 'capable of being said' as anything is capable of being said, e.g.:

Fry don 't stickle never Harold seeming (P.A. Gaeng).

'Grammatical' means simply 'corresponding to the grammar'. The native speaker of a language has a set of rules in his mind, an internal grammar, so to speak, which enables him to judge whether a given sentence is grammatical or not. It is this intuitive knowledge of the language as a system that enables the native speaker to produce and understand sentences which he may have never said or heard before. So, structuralists rely on their own intuition as speakers of English in distinguishing between grammatical and ungrammatical constructions.

All kernel sentences contain two main parts: a noun phrase (NP) and a verb phrase (VP): S -> NP -r VP. This formula, according to P. Roberts, means not only that a kernel consists of a NP and a VP, but that the NP comes first and the VP second; in other words, all kernel sentences are declarative. Kernels are few in number. Z.S. Harris mentions 7 types of kernel sentences in the English language.

NV: He paused (J. Joyce).

NVN: She left the room (A. Christie).

NVPN: Barbara looked at Peter (E, Blyton).

N is N: Tony is a student (V. Evans).

N is A: Susan is American (V. Evans).

N is PN: She is from London (V. Evans).

N is D: Their secret is out (Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English).

R.B. Lees thinks that the basic structures may be reduced to two: NV and N is N/A.

All the other sentences of the language are obtained by applying one or more transformations to kernel sentences. Kernel sentences, as basic structures, are characterized by a high frequency of occurrence. Transformed sentences are naturally more rare.

Transformations should be performed in accordance with certain rules. The generation of negative sentences, for instance, goes through two stages. First, the kernel declarative sentence is made emphatic either by introducing the accented function word do before the verb if it is in the present or past indefinite or by stressing the copular verb be, proper, or modal auxiliary, Cf:

251

The door opened (E. Blyton). —» The door did open.

He's afraid of his sister (J. Irving). -^ He is afraid of his sister.

His fingers were trembling (M Quin). —> His fingers were trembling.

We must see them (L Collier). —* We must see them.

Then the emphatic sentence is transformed into negative by inserting the negation not (or its contracted variant n't} after the stressed do, be, modal, or proper auxiliary. Cf.:

The door did open. —> The door did not (didn 't) open.

He is afraid of his sister. —> He is not (isn't) afraid of his sister.

We must see them. —» We must not (mustn 't) see them.

His fingers were trembling. —> His fingers were not (weren't) trembling.

Negative sentences are formed directly from kernel declarative sentences:

1) with the help of negative substitutes, e.g.:

Every one can leave. —> No one can leave (E. Hemingway);

2) by introducing negative words, such as never, nowhere,

etc., e.g.:

He touches wine (D. Parker). —»• He never touches wine (D. Parker).

The generation of general questions also goes through two stages.

1. The kernel declarative sentence is changed into emphatic,

e.g.:

He likes cucumbers (D. Parker). -* He does like cucumbers.

2. The function word does changes positions with the noun

phrase, the resulting structure comes to be pronounced with a rising

tone; a general question comes into existence:

He does like cucumbers. —* Does he like cucumbers'?

Special questions generally make a third stage necessary when some component of a general question is substituted by an interrogative word, e.g.:

Does he like cucumbers? —»- What does he like!

Special questions to the subject and its attribute are derived directly from kernel declarative sentences by substituting the subject or its attribute for an interrogative word, e.g.:

252

The people said nothing (J. Aldridge). —» Who said nothing1?

The fat boy thought for a moment (W. Golding). —»• What boy thought for a moment?

The intonation contour of the transformed special question is the same as that of the kernel declarative sentence.

The procedure of the passive transformation is as follows:

1) the second noun phrase is placed before the verb,

2) the verb is expanded according to the formula of the passive

voice be + -en,

3) the first noun phrase with the preposition by at the head is

put after the verb (the third step is optional), e.g.:

/ sent some beautiful roses (R. Lardner), —» Some beautiful roses were sent (by me).

The transformational model is also effective in producing complex sentences. Thus, two sentences can be joined into a complex sentence by w/2-relativizers or subordinates. Cf.:

This is the place. They met last in this place. —» This is the place where they last met (N.F. Irtenyeva et ah).

He did not come. He was ill. -~*• He did not come because he •was ill (N.F. Irtenyeva et al.)-

So, as an inter-sentence model, the transformational model is the most powerful among those discussed above, although it is not devoid of weak points either. For instance, it does not help analyze impersonal sentences, sentences of the kind / am prettier than her (M. Swan), sentences with homogeneous parts, and sentences with non-finite forms of the verb.

As an intra-sentence model, it has certain advantages, too. Thus, it is only the transformational model that helps explain the difference between John is eager to please, where John is the agent of the action, and John is easy to please, where John is the recipient of the action. Cf.:

John is eager to please. —» John eagerly pleases everybody.

John is easy to please. —> It easily pleases John.

However, being primarily formal, the transformational model cannot be consistent in classifying sentence components according to their role in realizing predication. The so-called kernel sentences do remind one of the predicative basis of a sentence. On closer inspection, however, it becomes evident that the two notions are by no means identical because Z.S. Harris's list of kernel sentences

253

comprises not only the predicative basis proper but also its expansion (e.g.: NVN, NVPN). As for the expansion of the predicative basis, it is treated indiscriminately in the transformational model, although it does present a rather heterogeneous phenomenon.

There is a very ramified (with many branches) set of nominalizing transformations in English. Nominalizing transformations nominalize a sentence, i.e. change it to a form that can appear in one of the NP (noun phrase) positions of another sentence and keep the same relations between their form classes that characterize the sentences from which they are derived. Cf:

The seagull shrieked —» the shriekfing) of the seagull (N.F. Irtenyeva et al.) - actor — action.

The man has a son —* the man's son (N.F. Irtenyeva et al.) — possession.

The question arises why native speakers of English frequently use N-transforms. The first reason is that no lexicon can be large enough to contain names for all the things about which at some time or other we shall speak and for which we must have distinct names. The second reason for using N-transforms is that they make English sentences more compact as compared with complex sentences.

The transformation of nominal izati on is mostly applied to kernel sentences. The study of nominalized kernel sentences has shown that the main procedures applied at the syntactic level are the following:

1) deletion of be, have and of the verbs of the same groups,

such as contain, consist, lie, stretch, etc.;

2) the introduction of prepositions (mostly, the preposition of}

between the two noun phrases;

3) permutation of the noun phrases. Cf.:

The information is of some value —> the information of some value (N.F. Irtenyeva et al.).

The room has three windows —+ the room with three windows (N.F. Irtenyeva et al.).

The table has three legs —> the legs of the table (N.F. Irtenyeva et al.).

At the morphemic level, the following procedures are used:

1) the derivation of a noun from the verb or adjective,

254

2) the transformation of a finite verb into an mg-form with a

possessive subject or embedding it between the determiner and the

noun,

3) the transformation of a finite verb into an infinitive

preceded by 'for + noun' as subject. Cf.:

He manages the bank —* the manager of the bank (N.F. Irtenyeva etal).

The bird sings —* the bird's singing; the singing bird; for the bird to sing <is natural> (N.F. Irtenyeva et al.).

Passive transforms can be also nominalized. The operations applied are: 1) deletion of be, 2) embedding of Participle II between the determiner and the noun, e.g.:

The bear was killed —* the killed bear (N.F. Irtenyeva et al.).

Three degrees of nominalizatiort can be distinguished.

1. The slightest degree of nominalization, when the only trait

of nominalization is the capability of a finite clause to stand in the

NP position, e.g.

How you manage on your income is a puzzle to me (The New

Webster's Grammar Guide).

2. The low degree of nominalization, when the N-transform,

capable of standing in the NP position, is a non-finite form of the

verb, e.g.:

/ suggested going home (A.S. Hornby, A.P. Cowie,

A.C. Gimson),

3. The highest degree of nominalization, when the nominal

structure has no verb, finite or non-finite, e.g.:

The girl is pretty —*• the pretty girl (N.F. Irtenyeva et al.).

Structural Sentence Patterns

The structural sentence patterns, singled out by N.Y, Shvedova in the sixties of the 20th century, comprise only the predicative minimum of a sentence. Cf.:

n! - Vf — Jlec uiyMum (PyccKas rpaMMarHKa).

ni - Ni -™ Bpam - yvumeJib (PyccKaa rpaMMaTHKa).

n! - Adj! n(WH_ .j, — Pe6enoK yMHw.it (PyccKaa rpaMMaiHKa)3.

3 N stands for a noun, Vf - for a finite verb, Adj - for an adjective, the icdex, stands for the nominative case (the first case in the case paradigm).

255

Starting on the assumption that the sentence is a unit of communication, first and foremost, T.P. Lomtev, D.N. Shmelev and many others question the validity of a purely formal approach to the definition of a structural sentence pattern. They say that a structural sentence pattern must be not only formally but also communicatively sufficient to realize a certain situation.

In the opinion of V.A. Beloshapkova, the two interpretations of structural sentence patterns supplement each other, representing, as it were, two different levels of abstraction: a higher level of abstraction in the case of orientation on the predicative minimum and a lower level of abstraction in the case of orientation on the communicative minimum. Accordingly, she suggests that a distinction should be drawn between minimal and expanded structural sentence patterns.

The differentiation of the predicative basis of a sentence and its expansion is, no doubt, a considerable step forward in sentence analysis. Of great importance are also the syntactic (word order) and morphological characteristics of all the sentence components.

However, since every practical grammar devotes special sections to the ways of expressing parts of the sentence, with the sole difference that it does this in words, not in symbols, we shall perform sentence analysis in the traditional terms of parts of the sentence.

Дата добавления: 2018-09-22; просмотров: 1289; Мы поможем в написании вашей работы! |

Мы поможем в написании ваших работ!