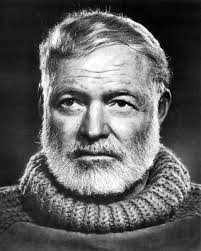

An American author and journalist

Hemingway is noted for economical and understated style, which he himself characterized as the iceberg theory: the facts float above water; the supporting structure and symbolism operate out of sight. His iceberg theory of omission is the foundation on which he builds. The syntax, which lacks subordinating conjunctions, creates static sentences. The photographic "snapshot" style creates a collage of images. Many types of internal punctuation (colons, semicolons, dashes, parentheses) are omitted in favor of short declarative sentences. The sentences build on each other, as events build to create a sense of the whole. Multiple strands exist in one story; an "embedded text" bridges to a different angle. He also uses other cinematic techniques of "cutting" quickly from one scene to the next; or of "splicing" a scene into another. Intentional omissions allow the reader to fill the gap, as though responding to instructions from the author, and create three-dimensional prose. In his literature, and in his personal writing, Hemingway habitually used the word "and" in place of commas. This use of polysyndeton may serve to convey immediacy. Hemingway's polysyndetonic sentence — or in later works his use of subordinate clauses — uses conjunctions to juxtapose startling visions and images.

Hemingway is noted for economical and understated style, which he himself characterized as the iceberg theory: the facts float above water; the supporting structure and symbolism operate out of sight. His iceberg theory of omission is the foundation on which he builds. The syntax, which lacks subordinating conjunctions, creates static sentences. The photographic "snapshot" style creates a collage of images. Many types of internal punctuation (colons, semicolons, dashes, parentheses) are omitted in favor of short declarative sentences. The sentences build on each other, as events build to create a sense of the whole. Multiple strands exist in one story; an "embedded text" bridges to a different angle. He also uses other cinematic techniques of "cutting" quickly from one scene to the next; or of "splicing" a scene into another. Intentional omissions allow the reader to fill the gap, as though responding to instructions from the author, and create three-dimensional prose. In his literature, and in his personal writing, Hemingway habitually used the word "and" in place of commas. This use of polysyndeton may serve to convey immediacy. Hemingway's polysyndetonic sentence — or in later works his use of subordinate clauses — uses conjunctions to juxtapose startling visions and images.

The leitmotif of most Hemingway’s literary work is the domineering feeling of the ‘lost generation’ which is incorporated in the emptiness and broken consciousness, solitude and misunderstanding. The man is inseparable from the mankind, he is responsible for everyone and everyone is responsible for the tragedy of a single person.

Summary of main features:

1) iceberg theory;

2) simple language;

3) unvarnished descriptions;

4) school-like grammar;

5) short, declarative sentences;

6) symbols;

7) repetitions;

Artificial dialogues.

Cat in the Rain

There were only two Americans stopping at the hotel. They did not know any of the people they passed on the stairs on their way to and from their room. Their room was on the second floor facing the sea. It also faced the public garden and the war monument. There were big palms and green benches in the public garden. In the good weather there was always an artist with his easel. Artists liked the way the palms grew and the bright colors of the hotels facing the gardens and the sea. Italians came from a long way off to look up at the war monument. It was made of bronze and glistened in the rain. It was raining. The rain dripped from the palm trees. Water stood in pools on the gravel paths. The sea broke in a long line in the rain and slipped back down the beach to come up and break again in a long line in the rain. The motor cars were gone from the square by the war monument. Across the square in the doorway of the cafe a waiter stood looking out at the empty square.

|

|

|

The American wife stood at the window looking out. Outside right under their window a cat was crouched under one of the dripping green tables. The cat was trying to make herself so compact that she would not be dripped on.

"I'm going down and get that kitty," the American wife said.

"I'll do it," her husband offered from the bed.

"No, I'll get it. The poor kitty out trying to keep dry under a table."

The husband went on reading, lying propped

up with the two pillows at the foot of the bed.

"Don't get wet," he said.

The wife went downstairs and the hotel owner stood up and bowed to her as she passed the office. His desk was at the far end of the office. He was an old man and very tall.

"Il piove,[1]" the wife said. She liked the hotel-keeper.

"Si, si, Signora, brutto tempo.[2] It's very bad weather."

He stood behind his desk in the far end of the dim room. The wife liked him. She liked the deadly serious way he received any complaints. She liked his dignity. She liked the way he wanted to serve her. She liked the way he felt about being a hotel-keeper. She liked his old, heavy face and big hands.

Liking him she opened the door and looked out. It was raining harder. A man in a rubber cape was crossing the empty square to the cafe. The cat would be around to the right. Perhaps she could go along under the eaves. As she stood in the doorway an umbrella opened behind her. It was the maid who looked after their room.

"You must not get wet," she smiled, speaking Italian. Of course, the hotel-keeper had sent her. With the maid holding the umbrella over her, she walked along the gravel path until she was under their window. The table was there, washed bright green in the rain, but the cat was gone. She was suddenly disappointed. The maid looked up at her.

|

|

|

"Ha perduto qualque cosa, Signora?[3]"

"There was a cat," said the American girl.

"A cat?"

"Si, il gatto."

"A cat?" the maid laughed. "A cat in the rain?"

"Yes," she said, "under the table." Then, "Oh, 1 wanted it so much. I wanted a kitty."

When she talked English the maid's face lightened.

"Come, Signora," she said. "We must get back inside. You will be wet."

''I suppose so," said the American girl.

They went back along the gravel path and passed in the door. The maid stayed outside to close the umbrella. As the American girl passed the office, the padrone bowed from his desk. Something felt very small and tight inside the girl. The padrone made her feel very small and at the same time really important. She had a momentary feeling of being of supreme importance. She went on up the stairs. She opened the door of the room. George was on the bed, reading.

"Did you get the cat?" he asked, putting the book down.

"It was gone."

"Wonder where it went to," he said, resting his eyes from reading.

She sat down on the bed.

"I wanted it so much," she said. "I don't know why I wanted it so much. I wanted that poor kitty. It isn't any fun to be a poor kitty out in the rain."

George was reading again.

She went over and sat in front of the mirror of the dressing table looking at herself with the hand glass. She studied her profile, first one side and then the other. Then she studied the back of her head and her neck.

"Don't you think it would be a good idea if I let my hair grow out?" she asked, looking at her profile again.

George looked up and saw the back of her neck, clipped close like a boy's.

"I like it the way it is."

"I get so tired of it," she said. "I get so tired of looking like a boy."

George shifted his position in the bed. He hadn't looked away from her since she started to speak.

|

|

|

"You look pretty darn nice,""' he said.

She laid the mirror down on the dresser and went over to the window and looked out. It was getting dark.

"I want to pull my hair back tight and smooth and make a big knot at the back that I can feel," she said. "I want to have a kitty to sit on my lap and purr when 1 stroke her."

"Yeah?" George said from the bed.

"And I want to eat at a table with my own silver and I want candles. And I want it to be spring and I want to brush my hair out in front of a mirror and I want a kitty and I want some new clothes."

"Oh, shut up and get something to read," George said. He was reading again.

His wife was looking out of the window. It was quite dark now and still raining in the palm trees.

"Anyway, I want a cat," she said, "I want a cat. I want a cat now. If I can't have long hair or any fun, I can have a cat".

George was not listening. He was reading his book. His wife looked out of the window where the light had come on in the square.

Someone knocked at the door.

"Avanti," George said. He looked up from his book.

In the doorway stood the maid. She held a big tortoise-shell cat pressed tight against her and swung down against her body.

"Excuse me," she said, "the padrone asked me to bring this for the Signora."

A Canary for One

The train passed very quickly a long, red stone house with a garden and four thick palm-trees with tables under them in the shade. On the other side was the sea. Then there was a cutting through red stone and clay, and the sea was only occasionally and far below against rocks.

«I bought him in Palermo» the American lady said. «We only had an hour ashore and it was Sunday morning. The man wanted to be paid in dollars and I gave him a dollar and a half. He really sings very beautifully».

It was very hot in the train and it was very hot in the lit salon compartment. There was no breeze came through the open window. The American lady pulled the window-blind down and there was no more sea, even occasionally. On the other side there was glass, then the corridor, then an open window, and outside the window were dusty trees and an oiled road and flat fields of grapes, with gray-stone hills behind them.

|

|

|

There was smoke from many tall chimneys — coming into Marseilles, and the train slowed down and followed one track through many others into the station. The train stayed twenty-five minutes in the station at Marseilles and the American lady bought a copy of The Daily Mail and a half-bottle of Evian water. She walked a little way along the station platform, but she stayed near the steps of the car because at Cannes, where it stopped for twelve minutes, the train had left with no signal of departure and she had gotten on only just in time. The American lady was a little deaf and she was afraid that perhaps signals of departure were given and that she did not hear them.

The train left the station in Marseilles and there was not only the switch-yards and the factory smoke but, looking back, the town of Marseilles and the harbor with stone hills behind it and the last of the sun on the water. As it was getting dark the train passed a farmhouse burning in a field. Motor-cars were stopped along the road and bedding and things from inside the farmhouse were spread in the field. Many people were watching the house burn. After it was dark the train was in Avignon. People got on and off. At the news-stand Frenchmen, returning to Paris, bought that day’s French papers. On the station platform were negro soldiers. They wore brown uniforms and were tall and their faces shone, close under the electric light. Their faces were very black and they were too tall to stare. The train left Avignon station with the negroes standing there. A short white sergeant was with them.

Inside the lit salon compartment the porter had pulled down the three beds from inside the wall and prepared them for sleeping. In the night the American lady lay without sleeping because the train was a rapide and went very fast and she was afraid of the speed in the night. The American lady’s bed was the one next to the window. The canary from Palermo, a cloth spread over his cage, was out of the draft in the corridor that went into the compartment wash-room. There was a blue light outside the compartment, and all night the train went very fast and the American lady lay awake and waited for a wreck.

In the morning the train was near Paris, and after the American lady had come out from the wash-room, looking very wholesome and middle-aged and American in spite of not having slept, and had taken the cloth off the birdcage and hung the cage in the sun, she went back to the restaurant-car for breakfast. When she came back to the lit salon compartment again, the beds had been pushed back into the wall and made into seats, the canary was shaking his feathers in the sunlight that came through the open window, and the train was much nearer Paris.

«He loves the sun,» the American lady said. «He’ll sing now in a little while.»

The canary shook his feathers and pecked into them. «I’ve always loved birds,» the American lady said. «I’m taking him home to my little girl. There — he’s singing now.»

The canary chirped and the feathers on his throats stood out, then he dropped his bill and pecked into his feathers again. The train crossed a river and passed through a very carefully tended forest. The train passed through many outside of Paris towns. There were tram-cars in the towns and big advertisements for the Belle Jardiniere and Dubonnet and Pernod on the walls toward the train. All that the train passed through looked as though it were before breakfast. For several minutes I had not listened to the American lady, who was talking to my wife.

«Is your husband American too?» asked the lady.

«Yes» said my wife. «We’re both Americans».

«I thought you were English».

«Oh, no».

«Perhaps that was because I wore braces,» I said. I had started to say suspenders and changed it to braces in the mouth, to keep my English character. The American lady did not hear. She was really quite deaf; she read lips, and I had not looked toward her. I had looked out of the window. She went on talking to my wife.

«I’m so glad you’re Americans. American men make the best husbands,» the American lady was saying. «That was why we left the Continent, you know. My daughter fell in love with a man in Vevey.» She stopped. «They were simply madly in love.» She stopped again. «I took her away, of course.»

«Did she get over it?» asked my wife.

«I don’t think so,» said the American lady. «She wouldn’t eat anything and she wouldn’t sleep at all. I’ve tried so very hard, but she doesn’t seem to take an interest in anything. She doesn’t care about things. I couldn’t have her marrying a foreigner.» She paused. «Some one, a very good friend, told me once, ‘No foreigner can make an American girl a good husband.’»

«No», said my wife, «I suppose not.» The American lady admired my wife’s travelling-coat, and it turned out that the American lady had bought her own clothes for twenty years now from the same maison de couture in the Rue Saint Honore. They had her measurements, and a vendeuse who knew her and her tastes picked the dresses out for her and they were sent to America. They came to the post-office near where she lived up-town in New York, and the duty was never exorbitant because they opened the dresses there in the post-office to appraise them and they were always very simple-looking and with no gold lace nor ornaments that would make the dresses look expensive. Before the present vendeuse, named Therese, there had been another vendeuse, named Amelie. Altogether there had only been these two in the twenty years. It had always been the same couturier. Prices, however, had gone up. The exchange, though, equalized that. They had her daughter’s measurements now too. She was grown up and there was not much chance of their changing now.

The train was now coming into Paris. The fortifications were levelled but grass had not grown. There were many cars standing on tracks — brown wooden restaurant-cars and brown wooden sleeping-cars that would go to Italy at five o’clock that night, if that train still left at five; the cars were marked Paris-Rome, and cars, with seats on the roofs, that went back and forth to the suburbs with, at certain hours, people in all the seats and on the roofs, if that were the way it were still done, and passing were the white walls and many windows of houses. Nothing had eaten any breakfast.

«Americans make the best husbands,» the American lady said to my wife. I was getting down the bags. «American men are the only men in the world to marry.»

«How long ago did you leave Vevey?» asked my wife.

«Two years ago this fall. It’s her, you know, that I’m taking the canary to.»

«Was the man your daughter was in love with a Swiss?»

«Yes,» said the American lady. «He was from a very good family in Vevey. He was going to be an engineer. They met there in Vevey. They used to go on long walks together.»

«I know Vevey,» said my wife. «We were there on our honeymoon.»

«Were you really? That must have been lovely. I had no idea, of course, that she’d fall in love with him.»

«It was a very lovely place,» said my wife.

«Yes,» said the American lady. «Isn’t it lovely? Where did you stop there?»

«We stayed at the Trois Couronnes,» said my wife.

«It’s such a fine old hotel,» said the American lady.

«Yes,» said my wife. «We had a very fine room and in the fall the country was lovely.»

«Were you there in the fall?»

«Yes,» said my wife.

We were passing three cars that had been in a wreck. They were splintered open and the roofs sagged in.

«Look,» I said. «There’s been a wreck.»

The American lady looked and saw the last car. «I was afraid of just that all night,» she said. «I have terrific presentiments about things sometimes. I’ll never travel on a rapide again at night. There must be other comfortable trains that don’t go so fast.»

Then the train was in the dark of the Gare de Lyons, and then stopped and porters came up to the windows. I handed bags through the windows, and we were out on the dim longness of the platform, and the American lady put herself in charge of one of three men from Cook’s who said: «Just a moment, madame, and I’ll look for your name.»

The porter brought a truck and piled on the baggage, and my wife said good-by and I said good-by to the American lady, whose name had been found by the man from Cook’s on a typewritten page in a sheaf of typewritten pages which he replaced in his pocket.

We followed the porter with the truck down the long cement platform beside the train. At the end was a gate and a man took the tickets.

We were returning to Paris to set up separate residences.

A Clean, Well-Lighted Place

It was very late and everyone had left the cafe except an old man who sat in the shadow the leaves of the tree made against the electric light. In the day time the street was dusty, but at night the dew settled the dust and the old man liked to sit late because he was deaf and now at night it was quiet and he felt the difference. The two waiters inside the cafe knew that the old man was a little drunk, and while he was a good client they knew that if he became too drunk he would leave without paying, so they kept watch on him.

"Last week he tried to commit suicide," one waiter said.

"Why?"

"He was in despair."

"What about?"

"Nothing."

"How do you know it was nothing?"

"He has plenty of money."

They sat together at a table that was close against the wall near the door of the cafe and looked at the terrace where the tableswere all empty except where the old man sat in the shadow of the leaves of the tree that moved slightly in the wind. A girl and a soldier went by in the street. The street light shone on the brass number on his collar. The girl wore no head covering and hurried beside him.

"The guard will pick him up," one waiter said.

"What does it matter if he gets what he's after?"

"He had better get off the street now. The guard will get him. They went by five minutes ago."

The old man sitting in the shadow rapped on his saucer with his glass. The younger waiter went over to him.

"What do you want?"

The old man looked at him. "Another brandy," he said.

"You'll be drunk," the waiter said. The old man looked at him. The waiter went away.

"He'll stay all night," he said to his colleague. "I'm sleepy now. I never get into bed before three o'clock. He should have killed himself last week."

The waiter took the brandy bottle and another saucer from the counter inside the cafe and marched out to the old man's table. He put down the saucer and poured the glass full of brandy.

"You should have killed yourself last week," he said to the deaf man. The old man motioned with his finger. "A little more," he said. The waiter poured on into the glass so that the brandy slopped over and ran down the stem into the top saucer of the pile. "Thank you," the old man said. The waiter took the bottle back inside the cafe. He sat down at the table with his colleague again.

"He's drunk now," he said.

"He's drunk every night."

"What did he want to kill himself for?"

"How should I know."

"How did he do it?"

"He hung himself with a rope."

"Who cut him down?"

"His niece."

"Why did they do it?"

"Fear for his soul."

"How much money has he got?" "He's got plenty."

"He must be eighty years old."

"Anyway I should say he was eighty."

"I wish he would go home. I never get to bed before three o'clock. What kind of hour is that to go to bed?"

"He stays up because he likes it."

"He's lonely. I'm not lonely. I have a wife waiting in bed for me."

"He had a wife once too."

"A wife would be no good to him now."

"You can't tell. He might be better with a wife."

"His niece looks after him. You said she cut him down."

"I know." "I wouldn't want to be that old. An old man is a nasty thing."

"Not always. This old man is clean. He drinks without spilling.Even now, drunk. Look at him."

"I don't want to look at him. I wish he would go home. He has no regard for those who must work."

The old man looked from his glass across the square, then over at the waiters.

"Another brandy," he said, pointing to his glass. The waiter who was in a hurry came over.

"Finished," he said, speaking with that omission of syntax stupid people employ when talking to drunken people or foreigners. "No more tonight. Close now."

"Another," said the old man.

"No. Finished." The waiter wiped the edge of the table with a towel and shook his head.

The old man stood up, slowly counted the saucers, took a leather coin purse from his pocket and paid for the drinks, leaving half a peseta tip. The waiter watched him go down the street, a very old man walking unsteadily but with dignity.

"Why didn't you let him stay and drink?" the unhurried waiter asked. They were putting up the shutters. "It is not half-past two."

"I want to go home to bed."

"What is an hour?"

"More to me than to him."

"An hour is the same."

"You talk like an old man yourself. He can buy a bottle and drink at home."

"It's not the same."

"No, it is not," agreed the waiter with a wife. He did not wish to be unjust. He was only in a hurry.

"And you? You have no fear of going home before your usual hour?"

"Are you trying to insult me?"

"No, hombre, only to make a joke."

"No," the waiter who was in a hurry said, rising from pulling down the metal shutters. "I have confidence. I am all confidence."

"You have youth, confidence, and a job," the older waiter said. "You have everything."

"And what do you lack?"

"Everything but work."

"You have everything I have."

"No. I have never had confidence and I am not young."

"Come on. Stop talking nonsense and lock up."

"I am of those who like to stay late at the cafe," the older waiter said.

"With all those who do not want to go to bed. With all those who need a light for the night."

"I want to go home and into bed."

"We are of two different kinds," the older waiter said. He was now dressed to go home. "It is not only a question of youth and confidence although those things are very beautiful. Each night I am reluctant to close up because there may be some one who needs the cafe."

"Hombre, there are bodegas open all night long."

"You do not understand. This is a clean and pleasant cafe. It is well lighted. The light is very good and also, now, there are shadows of the leaves."

"Good night," said the younger waiter.

"Good night," the other said. Turning off the electric light he continued the conversation with himself, It was the light of course but it is necessary that the place be clean and pleasant. You do not want music. Certainly you do not want music. Nor can you stand before a bar with dignity although that is all that is provided for these hours. What did he fear? It was not a fear or dread, It was a nothing that he knew too well. It was all a nothing and a man was a nothing too. It was only that and light was all it needed and a certain cleanness and order. Some lived in it and never felt it but he knew it all was nada y pues nada y naday pues nada. Our nada who art in nada, nada be thy name thy kingdom nada thy will be nada in nada as it is in nada. Give us this nada our daily nada and nada us our nada as we nada our nadas and nada us not into nada but deliver us from nada; pues nada. Hail nothing full of nothing, nothing is with thee. He smiled and stood before a bar with a shining steam pressure coffee machine.

"What's yours?" asked the barman.

"Nada."

"Otro loco mas," said the barman and turned away.

"A little cup," said the waiter.

The barman poured it for him.

"The light is very bright and pleasant but the bar is unpolished, "the waiter said.

The barman looked at him but did not answer. It was too late at night for conversation.

"You want another copita?" the barman asked.

"No, thank you," said the waiter and went out. He disliked bars and bodegas. A clean, well-lighted cafe was a very different thing. Now, without thinking further, he would go home to his room. He would lie in the bed and finally, with daylight, he would go to sleep. After all, he said to himself, it's probably only insomnia. Many must have it.

Hills Like White Elephants

The hills across the valley of the Ebro were long and white. On this side there was no shade and no trees and the station was between two lines of rails in the sun. Close against the side of the station there was the warm shadow of the building and a curtain, made of strings of bamboo beads, hung across the open door into the bar, to keep out flies. The American and the girl with him sat at a table in the shade, outside the building. It was very hot and the express from Barcelona would come in forty minutes. It stopped at this junction for two minutes and went to Madrid. ‘What should we drink?’ the girl asked. She had taken off her hat and put it on the table. ‘It’s pretty hot,’ the man said. ‘Let’s drink beer.’ ‘Dos cervezas,’ the man said into the curtain. ‘Big ones?’ a woman asked from the doorway. ‘Yes. Two big ones.’ The woman brought two glasses of beer and two felt pads. She put the felt pads and the beer glass on the table and looked at the man and the girl. The girl was looking off at the line of hills. They were white in the sun and the country was brown and dry. ‘They look like white elephants,’ she said. ‘I’ve never seen one,’ the man drank his beer. ‘No, you wouldn’t have.’ ‘I might have,’ the man said. ‘Just because you say I wouldn’t have doesn’t prove anything.’ The girl looked at the bead curtain. ‘They’ve painted something on it,’ she said. ‘What does it say?’ ‘Anis del Toro. It’s a drink.’ ‘Could we try it?’ The man called ‘Listen’ through the curtain. The woman came out from the bar. ‘Four reales.’ ‘We want two Anis del Toro.’ ‘With water?’

‘Do you want it with water?’ ‘I don’t know,’ the girl said. ‘Is it good with water?’ ‘It’s all right.’ ‘You want them with water?’ asked the woman. ‘Yes, with water.’ ‘It tastes like liquorice,’ the girl said and put the glass down. ‘That’s the way with everything.’ ‘Yes,’ said the girl. ‘Everything tastes of liquorice. Especially all the things you’ve waited so long for, like absinthe.’ ‘Oh, cut it out.’ ‘You started it,’ the girl said. ‘I was being amused. I was having a fine time.’ ‘Well, let’s try and have a fine time.’ ‘All right. I was trying. I said the mountains looked like white elephants. Wasn’t that bright?’ ‘That was bright.’ ‘I wanted to try this new drink. That’s all we do, isn’t it – look at things and try new drinks?’ ‘I guess so.’ The girl looked across at the hills. ‘They’re lovely hills,’ she said. ‘They don’t really look like white elephants. I just meant the colouring of their skin through the trees.’ ‘Should we have another drink?’ ‘All right.’ The warm wind blew the bead curtain against the table. ‘The beer’s nice and cool,’ the man said. ‘It’s lovely,’ the girl said. ‘It’s really an awfully simple operation, Jig,’ the man said. ‘It’s not really an operation at all.’ The girl looked at the ground the table legs rested on. ‘I know you wouldn’t mind it, Jig. It’s really not anything. It’s just to let the air in.’ The girl did not say anything. ‘I’ll go with you and I’ll stay with you all the time. They just let the air in and then it’s all perfectly natural.’ ‘Then what will we do afterwards?’ ‘We’ll be fine afterwards. Just like we were before.’ ‘What makes you think so?’

‘That’s the only thing that bothers us. It’s the only thing that’s made us unhappy.’ The girl looked at the bead curtain, put her hand out and took hold of two of the strings of beads. ‘And you think then we’ll be all right and be happy.’ ‘I know we will. You don’t have to be afraid. I’ve known lots of people that have done it.’ ‘So have I,’ said the girl. ‘And afterwards they were all so happy.’ ‘Well,’ the man said, ‘if you don’t want to you don’t have to. I wouldn’t have you do it if you didn’t want to. But I know it’s perfectly simple.’ ‘And you really want to?’ ‘I think it’s the best thing to do. But I don’t want you to do it if you don’t really want to.’ ‘And if I do it you’ll be happy and things will be like they were and you’ll love me?’ ‘I love you now. You know I love you.’ ‘I know. But if I do it, then it will be nice again if I say things are like white elephants, and you’ll like it?’ ‘I’ll love it. I love it now but I just can’t think about it. You know how I get when I worry.’ ‘If I do it you won’t ever worry?’ ‘I won’t worry about that because it’s perfectly simple.’ ‘Then I’ll do it. Because I don’t care about me.’ ‘What do you mean?’ ‘I don’t care about me.’ ‘Well, I care about you.’ ‘Oh, yes. But I don’t care about me. And I’ll do it and then everything will be fine.’ ‘I don’t want you to do it if you feel that way.’ The girl stood up and walked to the end of the station. Across, on the other side, were fields of grain and trees along the banks of the Ebro. Far away, beyond the river, were mountains. The shadow of a cloud moved across the field of grain and she saw the river through the trees. ‘And we could have all this,’ she said. ‘And we could have everything and every day we make it more impossible.’ ‘What did you say?’ ‘I said we could have everything.’ ‘We can have everything.’ ‘No, we can’t.’ ‘We can have the whole world.’ ‘No, we can’t.’ ‘We can go everywhere.’

‘No, we can’t. It isn’t ours any more.’ ‘It’s ours.’ ‘No, it isn’t. And once they take it away, you never get it back.’ ‘But they haven’t taken it away.’ ‘We’ll wait and see.’ ‘Come on back in the shade,’ he said. ‘You mustn’t feel that way.’ ‘I don’t feel any way,’ the girl said. ‘I just know things.’ ‘I don’t want you to do anything that you don’t want to do -’ ‘Nor that isn’t good for me,’ she said. ‘I know. Could we have another beer?’ ‘All right. But you’ve got to realize – ‘ ‘I realize,’ the girl said. ‘Can’t we maybe stop talking?’ They sat down at the table and the girl looked across at the hills on the dry side of the valley and the man looked at her and at the table. ‘You’ve got to realize,’ he said, ‘ that I don’t want you to do it if you don’t want to. I’m perfectly willing to go through with it if it means anything to you.’ ‘Doesn’t it mean anything to you? We could get along.’ ‘Of course it does. But I don’t want anybody but you. I don’t want anyone else. And I know it’s perfectly simple.’ ‘Yes, you know it’s perfectly simple.’ ‘It’s all right for you to say that, but I do know it.’ ‘Would you do something for me now?’ ‘I’d do anything for you.’ ‘Would you please please please please please please please stop talking?’ He did not say anything but looked at the bags against the wall of the station. There were labels on them from all the hotels where they had spent nights. ‘But I don’t want you to,’ he said, ‘I don’t care anything about it.’ ‘I’ll scream,’ the girl said. The woman came out through the curtains with two glasses of beer and put them down on the damp felt pads. ‘The train comes in five minutes,’ she said. ‘What did she say?’ asked the girl. ‘That the train is coming in five minutes.’ The girl smiled brightly at the woman, to thank her. ‘I’d better take the bags over to the other side of the station,’ the man said. She smiled at him. ‘All right. Then come back and we’ll finish the beer.’

He picked up the two heavy bags and carried them around the station to the other tracks. He looked up the tracks but could not see the train. Coming back, he walked through the bar-room, where people waiting for the train were drinking. He drank an Anis at the bar and looked at the people. They were all waiting reasonably for the train. He went out through the bead curtain. She was sitting at the table and smiled at him. ‘Do you feel better?’ he asked. ‘I feel fine,’ shesaid. ‘There’s nothing wrong with me. I feel fine.

The Killers

The door of Henry’s lunch-room opened and two men came in. They sat down at the counter.

‘What’s yours?’ George asked them.

‘I don’t know,’ one of the men said. ‘What do you want to eat, Al?’

‘I don’t know,’ said Al. ‘I don’t know what I want to eat.’

Outside it was getting dark. The street light came on outside the window. The two men at the counter read the menu. From the other end of the counter Nick Adams watched them. He had been talking to George when they came in.

‘I’ll have a roast pork tenderloin with apple sauce and mashed potatoes,' the first man said.

‘It isn’t ready yet.’

‘What the hell do you put it on the card for?’

‘That’s the dinner,’ George explained. ‘You can get that at six o'clock.’

George looked at the clock on the wall behind the counter.

‘It’s five o'clock’

‘The clock says twenty minutes past five,’ the second man said.

‘It’s twenty minutes fast.’

‘Oh, to hell with the clock,’ the first man said. ‘What have you got to eat?’

‘I can give you any kind of sandwiches,’ George said. ‘You can have ham and eggs, bacon and eggs, liver and bacon, or a steak.’

‘Give me chicken croquettes with green peas and cream sauce and mashed potatoes.’

‘That’s the dinner.’

‘Everything we want’s the dinner, eh? That’s the way you work it.’

‘I can give you ham and eggs, bacon and eggs, liver –’

‘I’ll take ham and eggs,’ the man called Al Said. He wore a derby hat and a black overcoat buttoned across the chest. His face was small and white and he had tight lips. He wore a silk muffler and gloves.

‘Give me bacon and eggs,’ said the other man. He was about the same size as Al. Their faces were different, but they were dressed like twins. Both wore overcoats too tight for them. They sat leaning forward, their elbows on the counter.

‘Got anything to drink?’ Al asked.

‘Silver beer, bevo, ginger-ale,’ George said.

‘I mean you got anything to drink?’

‘Just those I said.’

‘This is a hot town,’ said the other. ‘What do they call it?’

‘Summit,’

‘Ever hear of it?’ Al asked his friend.

‘No,’ said the friend.

‘What do you do here nights?’ Al asked.

‘They eat the dinner,’ his friend said. ‘They all come here and eat the big dinner.’

‘That’s right.’ George said.

‘So you think that’s right?’ Al asked George.

‘Sure.’

‘You’re a pretty bright boy, aren’t you?’

‘Sure,’ Said George.

‘Well, you’re not,’ said the other little man. ‘Is he, Al?’

‘He’s dumb,’ said Al. He turned to Nick. ‘What’s your name?’

‘Adams.’

‘Another Bright boy,’ Al said. ‘Ain’t he a bright boy, Max?’

‘The town’s full of bright boys,’ Max said.

George put down two platters, one of ham and eggs, the other of bacon and eggs, on the counter. He set down two side dishes of fried potatoes and closed the wicket into the kitchen.

‘Which is yours?’ he asked Al.

‘Don’t you remember?’

‘Ham and eggs,’

‘Just a bright boy,’ Max said. He leaned forward and took the ham and eggs. Both men ate with their gloves on. George watched them eat.

‘What are you looking at?’ Max looked at George.

‘Nothing.’

‘The hell you were. You were looking at me.’

‘Maybe the boy meant it for a joke, Max,’ Al said.

George laughed.

‘You don’t have to laugh,’ Max said to him. ‘You don’t have to laugh at all, see?’

‘All Right,’ said George.

‘So he think it's all right,’ Max turned to Al. ’He thinks it's all right. That’s a good one.’

‘Oh, he’s a thinker,’ Al said. They went on eating.

‘What’s the bright boy’s name down the counter?’ Al asked Max.

‘Hey, bright boy,’ Max said to Nick. ‘You go around on the other side of the counter with your boy friend.’

‘What’s the idea?’ Nick asked.

‘You better go around, bright boy,’ Al said. Nick went around behind the counter.

‘What’s the idea?’ George asked.

‘None of your damn business,’ Al said. ‘Who’s out in the kitchen?’

‘The nigger.’

‘What do you mean the nigger?’

‘The nigger that cooks.’

‘Tell him to come in,’

‘What’s the idea?’

‘Tell him to come in,’

‘Where do you think you are?’

‘We know damn well where we are,’ the man called Max said. ‘Do we look silly?’

‘You talk silly,’ Al said to him. ‘What the hell do you argue with this kid for? Listen,’ he said to George, ‘tell the nigger to come out here.’

‘What are you going to do to him?’

‘Nothing. Use your head, bright boy. What would we do to a nigger?’

George opened the slip that opened back into the kitchen. ‘Sam,’ he called. ‘Come in here a minute.’

The door of the kitchen opened and the nigger came in. ‘What was it?’ he asked. The two men at the counter took a look at him.

‘All right, nigger. You stand right there,’ Al said.

Sam, the nigger, standing in his apron, looked at the two men sitting at the counter. ‘Yes, sir,’ he said. Al got down from his stool.

‘I’m going back to the kitchen with the nigger and bright boy,’ he said. ‘Go back to the kitchen, nigger. You go with him, bright boy.’ The little man walked after Nick and Sam, the cook, back into the kitchen. The door shut after them. The man called Max sat at the counter opposite George. He didn’t look at George but looked in the mirror that ran along back of the counter. Henry’s had been made over from a saloon into a lunch-counter.

‘Well, bright boy,’ Max said, looking into the mirror, ‘why don’t you say something?’

‘What’s it all about?’

‘Hey, Al,’ Max called, ‘bright boy wants to know what it’s all about.’

‘Why don’t you tell him?’ Al’s voice came from the kitchen.

‘What do you think it’s all about?’

‘I don’t know.’

‘What do you think?’

Max looked into the mirror all the time he was talking.

‘I wouldn’t say.’

‘Hey Al, bright boy says he wouldn’t say what he thinks it’s all about.’

‘I can hear you, all right,’ Al said from the kitchen. He had propped open the slit that dishes passed through into the kitchen with a catsup bottle. ‘Listen, bright boy,’ he said from the kitchen to George. ‘Stand a little further along the bar. You move a little to the left, Max.’ He was like a photographer arranging for a group picture.

‘Talk to me, bright boy,’ Max said. ‘What do you think’s going to happen?’

George did not say anything.

‘I'll tell you,’ Max said. ‘We’re going to kill a Swede. Do you know a big Swede named Ole Anderson?

‘Yes.’

‘He comes in here to eat every night, don't he?’

‘Sometimes he comes here.’

‘He comes here at six o’clock, don’t he?

‘If he comes.’

‘We know all that, bright boy,’ Max said. ‘Talk about something else. Ever go to the movies?’

‘Once in a while.’

‘You ought to go to the movies more. The movies are fine for a bright boy like you.’

‘What are you going to kill Ole Anderson for? What did he ever do to you?’

‘He never had a chance to do anything to us. He never even seen us.’

‘What are you going to kill him for, then?’ George asked.

‘We’re killing him for a friend. Just to oblige a friend, bright boy.’

‘Shut up,’ said Al from the kitchen. ‘You talk too goddam much.’

‘Well, I got to keep bright boy amused. Don’t I, bright boy?’

‘You talk too damn much,’ Al said ‘The nigger and my bright boy are amused by themselves. I got them tied up like a couple of girl friends in the convent.’

‘I suppose you were in a convent.’

‘You never know.’

‘You were in a kosher convent. That’s where you were.’

George looked up at the clock.

‘If anybody comes in you tell them the cook is off, and if they keep after it, you tell them you’ll go back and cook yourself. Do you get that, bright boy?’

‘Al right,’ George said. ‘What you going to do with us afterward?’

‘That’ll depend,’ Max said. ‘That’s one of those things you never know at the time.’

George looked up at the clock. It was a quarter past six. The door from the street opened. A street-car motorman came in.

‘Hello, George,’ he said. ‘Can I get supper?’

‘Sam’s gone out,’ George said. ‘He’ll be back in about half an hour.’

‘I’d better go up the street,’ the motorman said. George looked at the clock. It was twenty minutes past six.

‘That was nice, bright boy,’ Max said ‘You’re a regular little gentleman.’

‘He knew I’d blow his head off,’ Al said from the kitchen.

‘No.’ said Max. ‘It ain’t that. Bright boy is nice. He’s a nice boy. I like him.’

At six-fifty-five George said: ‘He’s not coming.’

Two other people had been in the lunch-room. Once George had gone out to the kitchen and made a ham-and-eggs sandwich ‘to go’ that a man wanted to take with him. Inside the kitchen he saw Al, his derby hat tilted back, sitting on a stool beside the wicket with the muzzle of a sawed-off shotgun resting on the ledge. Nick and the cook were back to back in the corner, a towel tied in each of their mouths. George had cooked the sandwich, wrapped it up in oiled paper, put it in a bag, brought it in, and the man had paid for it and gone out.

‘Bright boy can do everything,’ Max said. ‘He can cook and everything. You’d make some girl a nice wife, bright boy.’

‘Yes?’ George said. ‘Your friend. Ole Anderson, isn’t going to come.’

‘We’ll give him ten minutes,’ Max said.

Max watched the mirror and the clock. The hands of the clock marked seven o’clock, and then five minutes past seven.

‘Come on, Al,’ said Max. ‘We better go. He's not coming.’

‘Better give him five minutes,’ Al said from the kitchen.

In the five minutes a man came in, and George explained that the cook was sick.

‘Why the hell don’t you get another cook?’ the man asked. ‘Aren’t you running a lunch-counter?’ He went out.

‘Come on Al,’ Max said.

‘What about the two bright boys and the nigger?’

‘They’re all right.’

‘You think so?’

‘Sure. We’re through with it.’

‘I don’t like it,’ said Al. ‘It’s sloppy. You talk too much.’

‘Oh, what the hell,’ said Max. ‘We got to keep amused, haven’t we?’

‘You talk too much, all the same,’ Al said. He came out from the kitchen. The cut-off barrels of the shotgun made a slight bulge under the waist of his too tight-fitting overcoat. He straightened his coat with his gloved hands.

‘So long, bright boy,’ he said to George. ‘You got a lot of luck.’

‘That’s the truth,’ Max said. ‘You ought to play the race, bright boy.’

The two of them went out of the door. George watched them, through the window, pass under the arc-light and cross the street. In their overcoats and derby hats they looked like a vaudeville team. George went back through the swinging-door into the kitchen and untied Nick and the cook.

‘I don’t want any more of that,’ said Sam, the cook. ‘I don’t want any more of that.’

Nick stood up. He had never had a towel in his mouth before.

‘Say,’ he said. ‘What the hell?’ He was trying to swagger it off.

‘They were going to kill Ole Anderson,’ George said. ‘They were going to shoot him when he came in to eat.

‘Ole Anderson?’

‘Sure.’

The cook felt the corners of his mouth with his thumbs.

‘They all gone?’ he asked.

‘Yeah,’ said George. ‘They’re gone now.’

‘I don’t like it,’ said the cook. ‘I don’t like any of it at all.’

‘Listen,’ George said to Nick. ‘You better go see Ole Anderson.’

‘All right.’

‘You better not have anything to do with it at all,’ Sam, the cook, said. ‘You better stay way out of it.’

‘Don’t go if you don’t want to,’ George said.

‘Mixing up in this ain’t going to get you anywhere,’ the cook said. ‘You stay out of it.’

‘I’ll go see him,’ Nick said to George. ‘Where does he live?’

The cook turned away.

‘Little boys always know what they want to do,’ he said.

‘He lives up at Hirsch’s rooming-house,’ George aid to Nick.

‘I’ll go up there.’

Outside, the arc-light shone through the bare branches of a tree. Nick walked up the street beside the car-tracks and turned at the next arc-light down a side-street. Three houses up the street was Hirsch’s rooming-house. Nick walked up the two steps and pushed the bell. A woman came to the door.

‘Is Ole Anderson here?’

‘Do you want to see him?’

‘Yes, if he’s in.’

Nick followed the woman up a flight of stairs and back to the end of the corridor. She knocked on the door.

‘Who is it?’

‘It's Nick Adams.’

‘Come in.’

Nick opened the door and went into the room. Ole Anderson was lying on the bed with all his clothes on. He had been a heavyweight prize-fighter and he was too long for the bed. He lay with his head on two pillows. He did not look at Nick.

‘What was it?’

‘I was up at Henry’s,’ Nick said, ’and two fellows came in and tied up me and the cook, and they said they were going to kill you.’

It sounded silly when he said it. Ole Anderson said nothing.

‘They put us out in the kitchen,’ Nick went on. ‘They were going to shoot you when you came in to supper.’

Ole Anderson looked at the wall and did not say anything.

‘George thought I’d better come and tell you about it.’

‘There isn’t anything I can do about it,’ Ole Anderson said.

‘I’ll tell you what they were like.’

‘I don’t want to know what they were like,’ Ole Anderson said. He looked at the wall. ‘Thanks for coming to tell me about it.’

‘That’s all right.’

Nick looked at the big man lying on the bed.

‘Don’t you want me to go and see the police?’

‘No,’ Ole Anderson said. ‘That wouldn’t do any good.’

‘Isn’t there something I could do?’

‘No. There ain’t anything to do.’

‘Maybe it was just a bluff.’

‘No, it ain’t just a bluff.’

Ole Anderson rolled over towards the wall.

‘The only thing is,’ he said, talking towards the wall, ‘I just can’t make up my mind to go out. I been in here all day.’

‘Couldn’t you get out of town?’

‘No,’ Ole Anderson said. ‘I’m through with all that running around.’

He looked at the wall.

‘There ain’t anything to do now.’

‘Couldn’t you fix it up some way?'

‘No. I got in wrong.’ He talked in the same flat voice. ‘There ain’t anything to do. After a while I’ll make up my mind to go out.’

‘I better go back and see George,’ Nick said.

‘So long,’ said Ole Anderson. He did not look towards Nick. ‘Thanks for coming around.’

Nick went out. As he shut the door he saw Ole Anderson with all his clothes on, lying on the bed looking at the wall.

‘He’s been in his room all day,’ the landlady said downstairs. ‘I guess he don’t feel well. I said to him: ‘‘Mr. Anderson, you ought to go out and take a walk on a nice fall day like this,’’ but he didn’t feel like it.’

‘He doesn’t want to go out.’

‘I’m sorry he don’t feel well,’ the woman said. ‘He’s an awfully nice man. He was in the ring, you know.’

‘I know it.’

‘You’d never know it expect from the way his face is,’ the woman said. They stood talking just inside the street door. ‘He’s just as gentle.’

‘Well, good-night, Mrs. Hirsch,’ Nick said.

‘I’m not Mrs. Hirsch’ the woman said. ‘She owns the place. I just look after it for her, I’m Mrs. Bell.’

‘Well, good-night, Mrs. Bell,’ Nick said.

‘Good-night,’ the woman said.

Nick walked up the dark street to the corner under the arc-light, and then along the car-tracks to Henry’s eating-house. George was inside, back of the counter.

‘Did you see Ole?

‘Yes,’ said Nick. ‘He’s in his room and he won’t go out.’

The cook opened the door from the kitchen when he heard Nick’s voice.

‘I don’t even listen to it,’ he said and shut the door.

‘Did you tell him about it?’ George asked.

‘Sure. I told him, but he knows what it’s all about.’

‘What’s he going to do?’

‘Nothing.’

‘They’ll kill him.’

‘I guess they will.’

‘He must have got mixed up in something in Chicago.’

‘I guess so,’ said Nick.

‘It’s a hell of a thing.’

‘It’s an awful thing,’ Nick said.

They did not say anything. George reached down for a towel and wiped the counter.

‘I wonder what he did?’ Nick said.

‘Double-crossed somebody. That’s what they kill them for.’

‘I’m going to get out of this town,’ Nick said.

‘Yes,’ said George. ‘That’s a good thing to do.’

‘I can’t stand to think about him waiting in the room and knowing he’s going to get it. It’s too damned awful.’

‘Well,’ said George, ‘You better not think about it.’

UP IN MICHIGAN

Jim Gilmore came to Hortons Bay from Canada. He bought the blacksmith shop from old man Horton. Jim was short and dark with big mustaches and big hands. He was a good horseshoer and did not look much like a blacksmith even with his leather apron on. He lived upstairs above the blacksmith shop and took his meals at D.J. Smith's.

Liz Coates worked for Smith's. Mrs. Smith, who was a very large clean woman, said Liz Coates was the neatest girl she'd ever seen. Liz had good legs and always wore clean gingham aprons and Jim noticed that her hair was always neat behind. He liked her face because it was so jolly but he never thought about her.

Liz liked Jim very much. She liked the way he walked over from the shop and often went to the kitchen door to watch for him to start down the road. She liked it about his mustache. She liked it about how white his teeth were when he smiled. She liked it very much that he didn't look like a blacksmith. She liked it how much D.J. Smith and Mrs. Smith liked Jim. One day she found that she liked it the way the hair was black on his arms and how white they were above the tanned line when he washed up in the washbasin outside the house. Liking that made her feel funny.

Hortons Bay, the town, was only five houses on the main road between Boyne City and Charlevoix. There was the general store and post office with a high false front and maybe a wagon hitched out in front, Smith's house, Stroud's house, Fox's house, Horton's house and Van Hoosen's house. The houses were in a big grove of elm trees and the road was very sandy. There was farming country and timber each way up the road. Up the road a ways was the Methodist church and down the road the other direction was the township school. The blacksmith shop was painted red and faced the school.

A steep sandy road ran down the hill to the bay through the timber. From Smith's back door you could look out across the woods that ran down to the lake and across the bay. It was very beautiful in the spring and summer, the sky blue and bright and usually whitecaps on the lake beyond the point from the breeze blowing in from Charlevoix and Lake Michigan. From Smith's back door Liz could see ore barges way out in the lake going toward Boyne City. When she looked at them they didn't seem to be moving at all but if she went in and dried some more dishes and then came out again they would be out of sight beyond the point.

All the time now Liz was thinking about Jim Gilmore. He didn't seem to notice her very much. He talked about the shop to D.J. Smith and about the Republican Party and about James G. Blaine. In the evenings he read The Toledo Blade and the Grand Rapids paper by the lamp in the front room or went out spearing fish in the bay with a jacklight with D.J. Smith. In the fall he and Smith and Charley Wyman took a wagon and tent, grubs, axes, their rifles and two dogs and went on a trip to the pine plains beyond Vanderbilt deer hunting. Liz and Mrs. Smith were cooking for four days for them before they started. Liz wanted to make something special for Jim to take but she didn't finally because she was afraid to ask Mrs. Smith for the eggs and flour and afraid if she bought them Mrs. Smith would catch her cooking. It would have been all right with Mrs. Smith but Liz was afraid.

All the time Jim was gone on the deer hunting trip Liz thought about him. It was awful while he was gone. She couldn't sleep well from thinking about him but she discovered it was fun to think about him too. If she let herself go it was better. The night before they were to come back she didn't sleep at all because it was all mixed up in a dream about not sleeping and really not sleeping. When she saw the wagon coming down the she felt weak and sick sort of inside. She couldn't wait till she saw Jim and it seemed as though everything would be all right when he came. The wagon stopped outside under the big elm and Mrs. Smith and Liz went out. All the men had beards and there were three deer in the back of the wagon, their thin legs sticking stiff over the edge of the wagon box. Mrs. Smith kissed Alonzo and he hugged her. Jim said "Hello, Liz," and grinned. Liz hadn't known just what would happen when Jim got back but she was sure it would be something. Nothing had happened. The men were just home, that was all. Jim pulled the burlap sacks off the deer and Liz looked at them. One was a big buck. It was stiff and hard to lift out of the wagon.

"Did you shoot it, Jim?" Liz asked.

"Yeah. Ain't it a beauty?" Jim got it onto his back to carry it to the smokehouse.

That night Charley Wyman stayed to supper at Smith's. It was too late to get back to Charlevoix. The men washed up and waited in the front room for supper.

"Ain't there something left in that crock, Jimmy?" D.J. Smith asked, and Jim went out to the wagon in the barn and fetched in the jug of whiskey the men had taken hunting with them. It was a four gallon jug and there was quite a little slopped back and forth in the bottom. Jim took a long pull on his way back to the house. It was hard to lift such a big jug up to drink out of it. Some of the whiskey ran down on his shirt front. The two men smiled when Jim came in with the jug. D.J. Smith sent for glasses and Liz brought them. D.J. poured out three big shots.

"Well, here's looking at you, D.J.," said Charley Wyman.

"That damn big buck, Jimmy," said D.J.

"Here's all the ones we missed, D.J.," said Jim, and downed his liquor.

"Tastes good to a man."

"Nothing like it this time of year for what ails you."

"How about another, boys?"

"Here's how, D.J."

"Down the creek, boys."

"Here's to next year."

Jim began to feel great. He loved the taste and the feel of whiskey. He was glad to be back to a comfortable bed and warm food and the shop. He had another drink. The men came in to supper feeling hilarious but acting very respectable. Liz sat at the table after she put on the food and ate with the family. It was a good dinner. The men ate seriously. After supper they went into the front room again and Liz cleaned up with Mrs. Smith. Then Mrs. Smith went upstairs and pretty soon Smith came out and went upstairs too. Jim and Charley were still in the front room. Liz was sitting in the kitchen next to the stove pretending to read a book and thinking about Jim. She didn't want to go to bed yet because she knew Jim would be coming out and she wanted to see him as he went out so she could take the way he looked up to bed with her.

She was thinking about him hard and then Jim came out. His eyes were shining and his hair was a little rumpled. Liz looked down at her book. Jim came over back of her chair and stood there and she could feel him breathing and then he put his arms around her. Her breasts felt plump and firm and the nipples were erect under his hands. Liz was terribly frightened, no one had ever touched her, but she thought, "He's come to me finally. He's really come."

She held herself stiff because she was so frightened and did not know anything else to do and then Jim held her tight against the chair and kissed her. It was such a sharp, aching, hurting feeling that she thought she couldn't stand it. She felt Jim right through the back of the chair and she couldn't stand it and then something clicked inside of her and the feeling was warmer and softer. Jim held her tight hard against the chair and she wanted it now and Jim whispered, "Come on for a walk."

Liz took her coat off the peg on the kitchen wall and they went out the door. Jim had his arm around her and every little way they stopped and pressed against each other and Jim kissed her. There was no moon and they walked ankle-deep in the sandy road through the trees down to the dock and the warehouse on the bay. The water was lapping in the piles and the point was dark across the bay. It was cold but Liz was hot all over from being with Jim. They sat down in the shelter of the warehouse and Jim pulled Liz close to him. She was frightened. One of Jim's hands went inside her dress and stroked over her breast and the other hand was in her lap. She was very frightened and didn't know how he was going to go about things but she snuggled close to him. Then the hand that felt so big in her lap went away and was on her leg and started to move up it.

"Don't, Jim," Liz said. Jim slid the hand further up.

"You musn't, Jim. You musn't." Neither Jim nor Jim's big hand paid any attention to her.

The boards were hard. Jim had her dress up and was trying to do something to her. She was frightened but she wanted it. She had to have it but it frightened her.

"You musn't do it, Jim. You musn't."

"I got to. I'm going to. You know we got to."

"No we haven't, Jim. We ain't got to. Oh, it isn't right. Oh, it's so big and it hurts so. You can't. Oh, Jim. Jim. Oh."

The hemlock planks of the dock were hard and splintery and cold and Jim was heavy on her and he had hurt her. Liz pushed him, she was so uncomfortable and cramped. Jim was asleep. He wouldn't move. She worked out from under him and sat up and straightened her skirt and coat and tried to do something with her hair. Jim was sleeping with his mouth a little open. Liz leaned over and kissed him on the cheek. He was still asleep. She lifted his head a little and shook it. He rolled his head over and swallowed. Liz started to cry. She walked over to the edge of the dock and looked down to the water. There was a mist coming up from the bay. She was cold and miserable and everything felt gone. She walked back to where Jim was lying and shook him once more to make sure. She was crying.

"Jim," she said. "Jim. Please, Jim."

Jim stirred and curled a little tighter. Liz took off her coat and leaned over and covered him with it. She tucked it around him neatly and carefully. Then she walked across the dock and up the steep sandy road to go to bed. A cold mist was coming up through the woods from the bay.

The Old Man at the Bridge

An old man with steel rimmed spectacles and very dusty clothes sat by the side of the road. There was a pontoon bridge across the river and carts, trucks, and men, women and children were crossing it. The mule-drawn carts staggered up the steep bank from the bridge with soldiers helping push against the spokes of the wheels. The trucks ground up and away heading out of it all and the peasants plodded along in the ankle deep dust. But the old man sat there without moving. He was too tired to go any farther.

It was my business to cross the bridge, explore the bridgehead beyond and find out to what point the enemy had advanced. I did this and returned over the bridge. There were not so many carts now and very few people on foot, but the old man was still there.

"Where do you come from?" I asked him.

"From San Carlos," he said, and smiled.

That was his native town and so it gave him pleasure to mention it and he smiled.

"I was taking care of animals," he explained.

"Oh," I said, not quite understanding.

"Yes," he said, "I stayed, you see, taking care of animals. I was the last one to leave the town of San Carlos."

He did not look like a shepherd nor a herdsman and I looked at his black dusty clothes and his gray dusty face and his steel rimmed spectacles and said, "What animals were they?"

"Various animals," he said, and shook his head. "I had to leave them."

I was watching the bridge and the African looking country of the Ebro Delta and wondering how long now it would be before we would see the enemy, and listening all the while for the first noises that would signal that ever mysterious event called contact, and the old man still sat there.

"What animals were they?" I asked.

"There were three animals altogether," he explained. "There were two goats and a cat and then there were four pairs of pigeons."

“And you had to leave them?" I asked.

"Yes. Because of the artillery. The captain told me to go because of the artillery."

"And you have no family?" I asked, watching the far end of the bridge where a few last carts were hurrying down the slope of the bank.

"No," he said, "only the animals I stated. The cat, of course, will be all right. A cat can look out for itself, but I cannot think what will become of the others."

"What politics have you?" I asked.

"I am without politics," he said. "I am seventy-six years old. I have come twelve kilometers now and I think now I can go no further."

"This is not a good place to stop," I said. "If you can make it, there are trucks up the road where it forks for Tortosa."

"I will wait a while," he said, " and then I will go. Where do the trucks go?"

"Towards Barcelona," I told him.

"I know no one in that direction," he said, "but thank you very much. Thank you again very much."

He looked at me very blankly and tiredly, and then said, having to share his worry with someone, "The cat will be all right, I am sure. There is no need to be unquiet about the cat. But the others. Now what do you think about the others?"

"Why they'll probably come through it all right."

"You think so?"

"Why not," I said, watching the far bank where now there were no carts.

"But what will they do under the artillery when I was told to leave because of the artillery?"

"Did you leave the dove cage unlocked?" I asked.

"Yes."

"Then they'll fly."

"Yes, certainly they'll fly. But the others. It's better not to think about the others," he said.

"If you are rested I would go," I urged. "Get up and try to walk now."

"Thank you," he said and got to his feet, swayed from side to side and then sat down backwards in the dust.

"I was taking care of animals," he said dully, but no longer to me. "I was only taking care of animals."

There was nothing to do about him. It was Easter Sunday and the Fascists were advancing toward the Ebro. It was a gray overcast day with a low ceiling so their planes were not up. That and the fact that cats know how to look after themselves was all the good luck that old man would ever have.

In Another Country

In the fall the war was always there, but we did not go to it any more. It was cold in the fall in Milan and the dark came very early. Then the electric lights came on, and it was pleasant along the streets looking in the windows. There was much game hanging outside the shops, and the snow powdered in the fur of the foxes and the wind blew their tails. The deer hung stiff and heavy and empty, and small birds blew in the wind and the wind turned their feathers. It was a cold fall and the wind came down from the mountains.

We were all at the hospital every afternoon, and there were different ways of walking across the town through the dusk to the hospital. Two of the ways were alongside canals, but they were long. Always, though, you crossed a bridge across a canal to enter the hospital. There was a choice of three bridges. On one of them a woman sold roasted chestnuts. It was warm, standing in front of her charcoal fire, and the chestnuts were warm afterward in your pocket. The hospital was very old and very beautiful, and you entered a gate and walked across a courtyard and out a gate on the other side. There were usually funerals starting from the courtyard. Beyond the old hospital were the new brick pavilions, and there we met every afternoon and were all very polite and interested in what was the matter, and sat in the machines that were to make so much difference.

The doctor came up to the machine where I was sitting and said: "What did you like best to do before the war? Did you practice a sport?"

I said: "Yes, football."

"Good," he said. "You will be able to play football again better than ever."

My knee did not bend and the leg dropped straight from the knee to the ankle without a calf, and the machine was to bend the knee and make it move as riding a tricycle. But it did not bend yet, and instead the machine lurched when it came to the bending part. The doctor said:" That will all pass. You are a fortunate young man. You will play football again like a champion."

In the next machine was a major who had a little hand like a baby's. He winked at me when the doctor examined his hand, which was between two leather straps that bounced up and down and flapped the stiff fingers, and said: "And will I too play football, captain-doctor?" He had been a very great fencer, and before the war the greatest fencer in Italy.

The doctor went to his office in a back room and brought a photograph which showed a hand that had been withered almost as small as the major's, before it had taken a machine course, and after was a little larger. The major held the photograph with his good hand and looked at it very carefully. "A wound?" he asked.

"An industrial accident," the doctor said.

"Very interesting, very interesting," the major said, and handed it back to the doctor.

"You have confidence?"

"No," said the major.

There were three boys who came each day who were about the same age I was. They were all three from Milan, and one of them was to be a lawyer, and one was to be a painter, and one had intended to be a soldier, and after we were finished with the machines, sometimes we walked back together to the Café Cova, which was next door to the Scala. We walked the short way through the communist quarter because we were four together. The people hated us because we were officers, and from a wine-shop someone called out, "A basso gli ufficiali![4]" as we passed. Another boy who walked with us sometimes and made us five wore a black silk handkerchief across his face because he had no nose then and his face was to be rebuilt. He had gone out to the front from the military academy and been wounded within an hour after he had gone into the front line for the first time. They rebuilt his face, but he came from a very old family and they could never get the nose exactly right. He went to South America and worked in a bank. But this was a long time ago, and then we did not any of us know how it was going to be afterward. We only knew then that there was always the war, but that we were not going to it any more.

We all had the same medals, except the boy with the black silk bandage across his face, and he had not been at the front long enough to get any medals. The tall boy with a very pale face who was to be a lawyer had been lieutenant of Arditi and had three medals of the sort we each had only one of. He had lived a very long time with death and was a little detached. We were all a little detached, and there was nothing that held us together except that we met every afternoon at the hospital. Although, as we walked to the Cova through the tough part of town, walking in the dark, with light and singing coming out of the wine-shops, and sometimes having to walk into the street when the men and women would crowd together on the sidewalk so that we would have had to jostle them to get by, we felt held together by there being something that had happened that they, the people who disliked us, did not understand.

We ourselves all understood the Cova, where it was rich and warm and not too brightly lighted, and noisy and smoky at certain hours, and there were always girls at the tables and the illustrated papers on a rack on the wall. The girls at the Cova were very patriotic, and I found that the most patriotic people in Italy were the café girls - and I believe they are still patriotic.

The boys at first were very polite about my medals and asked me what I had done to get them. I showed them the papers, which were written in very beautiful language and full of fratellanza and abnegazione[5], but which really said, with the adjectives removed, that I had been given the medals because I was an American. After that their manner changed a little toward me, although I was their friend against outsiders. I was a friend, but I was never really one of them after they had read the citations, because it had been different with them and they had done very different things to get their medals. I had been wounded, it was true; but we all knew that being wounded, after all, was really an accident. I was never ashamed of the ribbons, though, and sometimes, after the cocktail hour, I would imagine myself having done all the things they had done to get their medals; but walking home at night through the empty streets with the cold wind and all the shops closed, trying to keep near the street lights, I knew that Ì would never have done such things, and I was very much afraid to die, and often lay in bed at night by myself, afraid to die and wondering how I would be when back to the front again.

The three with the medals were like hunting-hawks; and I was not a hawk, although I might seem a hawk to those who had never hunted; they, the three, knew better and so we drifted apart. But I stayed good friends with the boy who had been wounded his first day at the front, because he would never know now how he would have turned out; so he could never be accepted either, and I liked him because I thought perhaps he would not have turned out to be a hawk either.

The major, who had been a great fencer, did not believe in bravery, and spent much time while we sat in the machines correcting my grammar. He had complimented me on how I spoke Italian, and we talked together very easily. One day I had said that Italian seemed such an easy language to me that I could not take a great interest in it; everything was so easy to say. "Ah, yes," the major said. "Why, then, do you not take up the use of grammar?" So we took up the use of grammar, and soon Italian was such a difficult language that I was afraid to talk to him until I had the grammar straight in my mind.

The major came very regularly to the hospital. I do not think he ever missed a day, although I am sure he did not believe in the machines. There was a time when none of us believed in the machines, and one day the major said it was all nonsense. The machines were new then and it was we who were to prove them. It was an idiotic idea, he said, "a theory like another". I had not learned my grammar, and he said I was a stupid impossible disgrace, and he was a fool to have bothered with me. He was a small man and he sat straight up in his chair with his right hand thrust into the machine and looked straight ahead at the wall while the straps thumbed up and down with his fingers in them.

"What will you do when the war is over if it is over?" he asked me. "Speak grammatically!"

"I will go to the States."

"Are you married?"

"No, but I hope to be."

"The more a fool you are," he said. He seemed very angry. "A man must not marry."

"Why, Signor Maggiore?"

"Don't call me Signor Maggiore."

"Why must not a man marry?"

"He cannot marry. He cannot marry," he said angrily. "If he is to lose everything, he should not place himself in a position to lose that. He should not place himself in a position to lose. He should find things he cannot lose."

He spoke very angrily and bitterly, and looked straight ahead while he talked. "But why should he necessarily lose it?"

"He'll lose it," the major said. He was looking at the wall. Then he looked down at the machine and jerked his little hand out from between the straps and slapped it hard against his thigh. "He'll lose it," he almost shouted. "Don't argue with me!" Then he called to the attendant who ran the machines. "Come and turn this damned thing off."

He went back into the other room for the light treatment and the massage. Then I heard him ask the doctor if he might use his telephone and he shut the door. When he came back into the room, I was sitting in another machine. He was wearing his cape and had his cap on, and he came directly toward my machine and put his arm on my shoulder.

"I am sorry," he said, and patted me on the shoulder with his good hand. "I would not be rude. My wife has just died. You must forgive me."

"Oh-" I said, feeling sick for him. "I am so sorry."

He stood there biting his lower lip. "It is very difficult," he said. "I cannot resign myself."

He looked straight past me and out through the window. Then he began to cry. "I am utterly unable to resign myself," he said and choked. And then crying, his head up looking at nothing, carrying himself straight and soldierly, with tears on both cheeks and biting his lips, he walked past the machines and out the door.

The doctor told me that the major's wife, who was very young and whom he had not married until he was definitely invalided out of the war, had died of pneumonia. She had been sick only a few days. No one expected her to die. The major did not come to the hospital for three days. Then he came at the usual hour, wearing a black band on the sleeve of his uniform. When he came back, there were large framed photographs around the wall, of all sorts of wounds before and after they had been cured by the machines. In front of the machine the major used were three photographs of hands like his that were completely restored. I do not know where the doctor got them. I always understood we were the first to use the machines. The photographs did not make much difference to the major because he only looked out of the window.

Indian Camp

At the lake shore there was another rowboat drawn up. The two Indians stood waiting.

Nick and his father got in the stern of the boat and the Indians shoved it off and one of them got in to row. Uncle George sat in the stern of the camp rowboat. The young Indian shoved the camp boat off and got in to row Uncle George.

The two boats started off in the dark. Nick heard the oarlocks of the other boat quite a way ahead of them in the mist. The Indians rowed with quick choppy strokes. Nick lay back with his father's arm around him. It was cold on the water. The Indian who was rowing them was working very hard, but the other boat moved further ahead in the mist all the time.

"Where are we going, Dad?" Nick asked.

"Over to the Indian camp. There is an Indian lady very sick."

"Oh," said Nick.

Across the bay they found the other boat beached. Uncle George was smoking a cigar in the dark. The young Indian pulled the boat way up on the beach. Uncle George gave both the Indians cigars.

They walked up from the beach through a meadow that was soaking wet with dew, following the young Indian who carried a lantern. Then they went into the woods and followed a trail that led to the logging road that ran back into the hills. It was much lighter on the logging road as the timber was cut away on both sides. The young Indian stopped and blew out his lantern and they all walled on along the road.

They came around a bend and a dog came out barking. Ahead were the lights of the shanties where the Indian bark-peelers lived. More dogs rushed out at them. The two Indians sent them back to the shanties. In the shanty nearest the road there was a light in the window. An old woman stood in the doorway holding a lamp.

Inside on a wooden bunk lay a young Indian woman. She had been trying to have her baby for two days. All the old women in the camp had been helping her. The men had moved off up the road to sit in the dark and smoke cut of range of the noise she made. She screamed just as Nick and the two Indians followed his father and Uncle George into the shanty. She lay in the lower bunk, very big under a quilt. Her head was turned to one side. In the upper bunk was her husband. He had cut his foot very badly with an ax three days before. He was smoking a pipe. The room smelled very bad.

Nick's father ordered some water to be put on the stove, and while it was heating he spoke to Nick.

"This lady is going to have a baby, Nick," he said.

"I know," said Nick.