The Problem of Phonetic Functional Styles Classification

Correlation between Extralinguistic and Linguistic Variation

It is common knowledge that the type of language we are using changes with the situation in which communication is carried on. A particular social situation makes us respond with an appropriate variety of language. We use one variety of language at home, another with our friends, a third at work, and so on. In other words, there are ‘appropriate’ linguistic ‘manners’ for the different types of situations in which language is used and we are expected to know these manners in our native language.

Varieties of language correlating with social situations are generally termed styles. The distinctive features of styles include language features of various kinds, among which phonetic modifications play the leading role in oral speech. The main circumstances of reality that course phonetic modification in speech are as follows:

· the aim of spontaneity of speech (which may be to instruct, to inform, to narrate, to chat, etc.);

· the extent of spontaneity of speech (unprepared speech, prepared speech);

· the nature of interchange, i.e. the use of a form of speech which may either suggest only listening, or both listening and an exchange of remarks (a lecture, a discussion, a conversation, etc.);

· social and psychological factors, which determine the extent of formality of speech and the attitudes expressed (a friendly conversation with close friends, a quarrel, an official conversation, etc.).

These circumstances, or factors, are termed extra-linguistic factors. Thus, different ways of pronunciation caused by extra-linguistic factors and characterized by definite phonetic features, are called phonetic styles, or styles of pronunciation.

Correlation between extra-linguistic and intra-linguistic variation does not necessarily imply that there are as many varieties of language (styles) as there are extra-linguistic situations. First of all, the factors, or dimensions, constituting an extra-linguistic situation are not equally important, as far as modification of language means is concerned. The greatest influence in this respect is exercised by such factors as the social status of the speakers and their relations to each other, the place of communication and its subject-matter (topic).

Significant variations within each of the given factors (dimensions) are most conveniently described in terms of an opposition: formal/ informal, and there is a strong tendency for identical features (formal or informal) from different dimensions to co-occur: an informal subject-matter tends to be combined with an informal sphere of communication and informal relations between the speakers and vice versa. Accordingly,

|

|

|

the broadest and most widely recognized division of English speech is into f o r m a l and i n f o r m a l s t y l e s.

The formal style covers those varieties of English that we hear from a lecturer, a public speaker, a radio announcer, etc. These types of communication are frequently reduced to monologue, addressed by one person to many, and are often used prepared in advance. They also include official and business talks.

The informal style is used in personal every day communication. This category embraces the most frequent and the most widespread occurrences of spoken English. Most typically informal speech takes the form of a conversation, although monologue is not infrequent either.

According to the degree of formality in one case and familiarity in the other, the two styles can be subdivided as follows:

1. Formal: a) formal-official (public speeches, official talks, etc.)

E.g.: A public speech

Mr. Higgins: I declare the meeting open and call upon the secretary to read the minutes of the last meeting.

Miss Jones: There are the minutes of the meeting of the Committee held at 4 p.m. on Friday 7th October… and the meeting closed at 5.25 p.m.

Mr. Higgins: Is it your wish that I sign these minutes as a correct record?

All: Yes.

b) formal-neutral (a lecturer, a teacher’s explanation, a business talk or an exchange of information between colleagues with variations depending on the status of the partners, a report on one’s work or research before a small group of people, etc.)

E.g. A business talk

– Good morning. Is this Mr. Howard’s office?

– John Howard?

– Yes. I was wondering whether Mr. Howard could see me. My name is Martell.

– Oh, yes, Miss Martell. Mr. Howard has a letter from your manager. He said you’d be writing to make an appointment.

– I decided to come instead. I was rather hoping that perhaps Mr. Howard would be able to see me this morning.

2. Informal:

|

|

|

a) informal-ordinary (a conversation on a train, bus, etc.; an exchange of remarks in a shop, café, post office, railway station, etc.; an everyday talk between friends, neighbours, schoolmates, etc.)

E.g. A talk in a shop

Assistant: You know, madam, I think the next size will be better.

Customer: Yes, it looks like it. But I’ve always taken a 36 hip size before. Have I really started putting on weight?

Assistant: You shouldn’t worry. You can’t trust sizes. Nowadays they seem to vary enormously. I’ll just get you the size above.

b) informal-familiar (everyday conversation between intimate friends, relatives)

E.g. A talk between mother and daughter

– Look, what a lovely bag I’ve bought.

– Not again! Why, you’ve got a collection of them.

– But you’ve no idea how cheap it was. A real bargain.

– Bargain my foot. You know we must save money.

– Getting good value is saving money.

– Oh, come on. Be your age.

This classification is, of course, very tentative and not at all complete. One could also outline further distinctions within each of the above-mentioned varieties. If, for example, we consider a dimension such as the number of people addressed it will be necessary to discriminate between public speeches at a big gathering (such as an open air meeting) and those made at a comparatively small gathering (such as a speech pronounced in a hall). The kind of the audience is also an important factor as far as phonetic modifications of speech are concerned. Thus, a teacher’s explanation meant for adults will differ phonetically as well as lexically and grammatically from that spoken to children.

Oral speech is a very complicated phenomenon, where too many factors are involved. Phonetic styles are related to social setting or circumstances in which language is used. It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a person speaks differently on different occasions (e.g. when chatting with intimate friends or talking to official persons, when delivering a lecture, speaking over the radio or giving a dictation exercise). In other words, the choice of a speech style is determined by the situation. Moreover, the problem of speech typology and phonetic differences conditioned by such extra-linguistic factors as age, sex, personality traits, status, occupation, purpose, social identity (or ‘class dialect’) and the emotional state of the speaker also bear on the issue.

|

|

|

The Problem of Phonetic Functional Styles Classification

Human communication isn’t possible without intonation, because it’s instrumental in conveying the meaning. No sentence can exist without a particular intonation.

Intonation is a language universal. It is a powerful means of communication. It has a great potential for expressing ideas and emotions and it contributes to mutual understanding between people.

Intonation is the music of the language. In English, we use tone to signal emotion, questioning, and parts of the sentence among many other things. It’s important to recognize the meaning behind the tones used in everyday speech, and to be able to use them so that there are no misunderstandings between the speaker and the listener. It is generally true that mistakes in pronunciation of sounds can be overlooked, but mistakes in intonation make a lasting impression.

Intonation is «the melody of speech». It is said to indicate the attitudes and emotions of the speaker, so that one and the same sentence can be pronounced in a happy way, a sad way, an angry way, and so on. It is clear that when we are expressing emotions, we also use different voice qualities, different speaking rates, facial expressions, gestures. We must indicate what type of information is presenting and how it is structured, and at the same time we must keep our listeners’ attention and their participation in the exchange of information.

Intonation plays a central role in stylistic differentiation of oral texts. Stylistically explicable deviations from intonational norms reveal conventional patterns differing from language to language. Adult speakers are both transmitters and receivers of the same range of phonostylistic effects carried by intonation. The intonation system of a language provides a consistently recognizable invariant basis of these effects from person to person. The uses of intonation in this function show that the information so conveyed is, in many cases, impossible to separate from lexical and grammatical meanings expressed by words and constructions in a language (verbal context) and from co-occurring situational information (non-verbal context). The meaning of intonation cannot be judged in isolation.

|

|

|

Thus the primary concern of linguistics is the study of language in use. It’s particularly relevant for the study of intonational functional styles, because we’re interested in how the language units are used in various social situations. An intonational style can be defined as a system of interrelated intonational means which is used in a certain social sphere and serves a definite aim in communication.

The problem of intonational styles classification can hardly be regarded as settled as yet. Several different styles of pronunciation may be distinguished, although no generally accepted classification of styles has been worked out and the peculiarities of different styles have not yet been sufficiently investigated. Most scholars do not argue about the number of styles being five, but disagree about their terminology. Besides, it should be noted that the phonetic style-forming means are the degree of assimilation,

reduction and elision, all of which depend on the degree of carefulness of pronunciation. Each phonetic style is characterized by a specific combination of certain segmental and prosodic features.

The British phonetician D. Jones distinguishes such styles of pronunciation as the rapid familiar style, the slower colloquial style, the natural style used in addressing a fair-sized audience, the acquired style of the stage, and the acquired style used in singing.

T. Kenyon described four principal styles of good spoken English: familiar colloquial, formal colloquial, public-speaking style and public-reading style.

L.V. Shcherba wrote of the need to distinguish a great variety of styles of speech, in accordance with the great variety of different social occasions and situations, but for the sake of simplicity he suggested that only two styles of pronunciation should be distinguished: (1) colloquial style characteristic of people’s quiet talk, and (2) full style, which we use when we want to make our speech especially distinct and, for this purpose, clearly articulate all the syllables of each word.

The other way of classifying phonetic styles is suggested by J.A. Dubovsky who discriminates the following styles: informal ordinary, formal neutral, formal official, informal familiar, declamatory. This division is based on different degrees of formality or rather familiarity between the speaker and the listener.

M. A. Sokolova and other’s approach is slightly different. And it is this very classification of phonostyles that is considered useful for teaching and learning purposes. According to M.A. Sokolova there are five intonational styles singled out mainly according to the purpose of communication. They are as follows:

Ø Informational (Formal) style;

Ø Academic (Scientific) style;

Ø Publicistic style;

Ø Declamatory (Artistic) style;

Ø Conversational (Familiar) style.

As we may see the above-mentioned phonetic styles on the whole correlate with functional styles of the language. They are differentiated on the basis of spheres of discourse. For instance, according to professor I.R. Galperin there are such verbal functional styles of the written language as: (1) belles-lettres style, embracing genres of creative writing; (2) publicistic style, covering such genres as essays, feature article, public speeches; (3) newspaper style, observed in the majority of materials printed in newspapers; (4) scientific prose style, found in articles, brochures, monographs and other scientific, academic publications; (5) the style of official documents.

These styles are the product of the development of the written variety of language. In the case of oral representation of written texts each verbal style is given a phonetic identity. Thus the situational context and the speaker’s purpose determine the choice of an intonational style. The primary situational determinant is the kind of relationship existing between the participants in a communicative transaction.

Intonational styles distinction is based on the assumption that there are types of information present in communication: intellectual information, emotional and

attitudinal (modal) information, volitional and desiderative information. Consequently, there are three types of intonation patterns used in oral communication: a) intonation patterns used for intellectual purposes, b) intonation patterns used for emotional and attitudinal purposes and c) intonation patterns used for volitional and desiderative purposes. All intonational styles include intellectual intonation patterns, because the aim of any kind of intercourse is to communicate or express some intellectual information. The frequency of occurrence and the overall intonational distribution of emotional and volitional patterns shape the distinctive features of each style.

Speech Typology

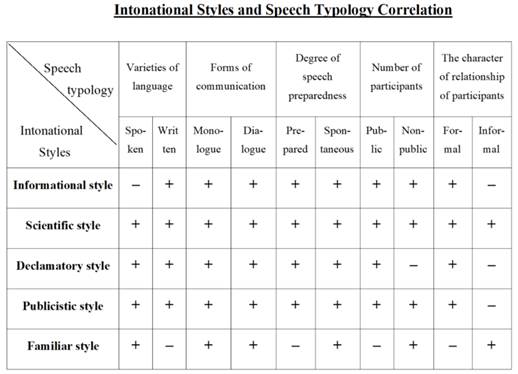

Analysis of most varieties of English speech shows that the intonational styles contrastivity is explicable only within the framework of speech typology, embracing primarily:

a) varieties of language;

b) forms of communication;

c) degree of speech preparedness;

d) the number of participants involved in communication;

e) the character of participants’ relationship.

Language in its full interaction has two varieties – spoken and written. The term ‘spoken’ is used in relation to oral texts produced by unconstrained speaking, while the term ‘written’ is taken to cover both oral representation of written texts (reading) and the kind of English that we sometimes hear in the language of public speakers and orators, or possibly in formal conversation (more especially between strangers).

According to the nature of the participation situation in which the speaker is involved two forms of communication are generally singled out – monologue and dialogue, the former being referred to as a one-sided type of conversation and the latter as a balanced one. Monologue is speaking of one individual; dialogue presupposes the participation of two or more speakers. Monologues are usually more extended and characterized by a greater lexical and grammatical cohesion. They are better organized.

Degree of speech preparedness entails distinction between prepared and spontaneous speech.

As far as the number of participants involved in communication is concerned, speech may be public and non-public.

And, finally, from the character of participants’ relationship viewpoint there are formal and informal types of speech.

Formal type of speech is designed to be intelligible to the general population of speakers of the language, whether or not they live in the same area or country. Its functioning is characterized by intentional approach of the speaker towards the choice of language means suitable for a particular communicative situation and the official, formal, serious, preplanned nature of the latter. There will be a standard or general vocabulary, grammar and syntax that are understood by the vast majority of speakers, so that information is shared with as little misunderstanding as possible.

Informal type of speech, on the contrary, is characterized by the immediacy, spontaneity, informality of the communicative situation. It is not premeditated. Alongside this consideration there exists a strong tendency to treat informal speech

as an individual language system with its independent set of language units and rules of their connection.

Thus, there is a distinct well-defined correlation between intonational styles and speech typology. In describing, for example, the intonation identity of familiar (conversational) style one has to take into account that it occurs in the spoken variety of English, both in one-sided (monologue) and balanced (dialogue) types of conversation, in spontaneous, non-public, informal discourse.

Intonational Styles and Speech Typology Correlation

Speech typology Varieties of language Forms of communication Degree of speech preparedness Number of participants The character of relationship of participants Spo- ken Writ ten Mono-logue Dia-logue Pre-pared Spon-taneous Pub-lic Non-public For-mal Infor-mal

Informational (Formal) Style

Informational (formal) style is characterized by predominant use of intellectual intonation patterns. It occurs in formal discourse where the task set by the sender of the message is to communicate information without giving it any emotional or volitional evaluation. This intonational style is used, for instance, by radio or television announcers when reading weather forecasts, news, or in various official situations. It is considered to be stylistically neutral.

When using informational the speaker is primarily concerned that each sentence type, such as declarative or interrogative, command or request, dependent or independent, is given an unambiguous intonational identity. The sender of the message consciously avoids giving any secondary values to utterances. It might interfere with the listener’s correct decoding the message and with inferring the principal point of information in the sentence. So in most cases the speaker sounds dispassionate.

The characteristic feature of informational style is the use of (Low-Pre-head + ) Falling Head + Low Fall (Low Rise) ( + Tail), normal or slow speed of utterance and regular rhythm. Less frequently the Stepping Head (characterized by an even, unchanged pitch level over each of the stress-groups) may be used instead of the Falling Head. In certain cases the Fall-Rise occurs, with the falling part of the tune indicating the main idea and the rising part making some addition to the main idea.

In informational style intonation never contrasts with lexical and grammatical meanings conveyed by words and constructions. Internal boundaries placement is semantically predictable, that is, an intonation group here always consists of words joined together by sense.

Besides, it is important to note that intonation groups tend to be short; duration of pauses varies from medium to long. Short pauses are rather rare.

Scientific (Academic) Style

In scientific (academic) style both intellectual and volitional intonation patterns are employed. The speaker’s purpose here is not only to prove a hypothesis, to create new concepts, to disclose relations between different phenomena, but also to direct the listener’s attention to the message carried in the semantic component. Although this style tends to be objective and precise, it is not entirely unemotional and devoid of any individuality. Scientific style is frequently used, for example, by university lecturers, schoolteachers, or by scientists in formal or informal discussions.

Attention is focused here on a lecture on a scientific subject and reading aloud a piece of scientific prose, that is to say, the type of speech that occurs in the written variety of language, in one-sided form of communication (monologue), in prepared, public, formal discourse. The lecturer’s purpose is threefold:

(a) he must get the ‘message’ of the lecture across to his audience;

(b) he must attract the attention of the audience and direct it to the ‘message’;

(c) he must establish contact with his audience and maintain it throughout the lecture.

To achieve these goals he appeals to a specific set of intonation means. The most common pre-nuclear pattern (that part of the tune preceding the nucleus) is (Low Pre-Head + ) Stepping Head. The Stepping Head makes the whole intonation group sound weighty and it has a greater persuasive appeal than the Falling Head. Occasionally the High Head may occur as a less emphatic variant of the Stepping Head. This enables the lecturer to sound categorical, judicial, considered and persuasive.

As far as the terminal tone is concerned, both simple and compound tunes occur here. The High Fall and the Fall-Rise are the most conspicuous tunes. They are widely used as means of both logical emphasis and emphasis for contrast. A succession of several high falling tones also makes an utterance expressive enough, they help the lecturer to impress on his audience that he is dealing with something he is quite sure of, something that requires neither argument nor discussion. Thus basic intonation patterns found here are as follows:

(Low Pre-Head + ) (Stepping Head + ) Low Fall ( + Tail)

(Low Pre-Head + ) (Stepping Head + ) High Fall ( + Tail)

(Low Pre-Head + ) (Stepping Head + ) Low Rise ( + Tail)

(Low Pre-Head + ) (High (Medium) Level Head + ) Fall-Rise ( + Tail)

(Low Pre-Head + ) (High (Medium) Level Head + ) Mid-Level ( + Tail)

Variations and contrasts in the speed of utterance are indicative of the degree of importance attached to different parts of the speech flow. Less important parts are pronounced at greater speed than usual, while more important parts are characterized by slower speed. Diminished and increased loudness helps the listeners to perceive a word as being brought out.

Internal boundaries placement is not always semantically predictable. Some pauses, made by the speaker, may be explicable in terms of hesitation phenomena denoting forgetfulness or uncertainty (eg. word searching). The most widely used hesitation phenomena here are repetitions of words and filled pauses, which may be vocalic [ə(з:)], consonantal [m] and mixed [əm(з:m)]. Intentional use of these effects enables the lecturer to obtain a balance between formality and informality and thus to establish a closer contact with his listeners who feel that they are somehow involved in making up the lecture. Moreover, a silent pause at an unexpected point calls the listeners’ attention and may serve the speaker’s aim to bring out some words in an utterance.

In the case of reading aloud scientific prose the most widely used pre-nuclear pattern is also (Low Pre-Head + ) Stepping Head. Sometimes the broken Stepping Head is found, if

an accidental rise occurs on some item of importance. The Stepping Head may be replaced by the so-called heterogeneous head, i.e. a combination of two or several heads. Occasionally the Scandent (Climbing) Head (characterized by an upward pitch movement over the stress-groups) is employed which is an efficient means of making a sentence or an intonation group more emphatic. Final intonation groups are pronounced predominately with the low or the high falling tone. Non-final intonation groups present more possibilities of variations. In addition to the simple tunes found in final intonation groups the following compound tunes are used: the Fall-Rise and the Rise-Fall. But the falling nuclear tone ranks first, the Low Rise or Mid-Level are much less common.

It should be borne in mind that the falling nuclear tone in non-final intonation groups in most cases does not reach the lowest possible pitch level. Compound tunes make the oral representation of a written scientific text more expressive by bringing out the most important items in an utterance. Moreover, they secure greater intonational cohesion between different parts of a text. Thus the following intonation patterns may be added to those listed above:

(Low Pre-Head + ) (Stepping Head + ) Rise-Fall ( + Tail)

(Low Pre-Head + ) (Heterogeneous Head + ) Low Fall ( + Tail)

(Low Pre-Head + ) (Heterogeneous Head + ) High Fall ( + Tail)

(Low Pre-Head + ) (Heterogeneous Head + ) Fall-Rise ( + Tail)

(Low Pre-Head + ) (Sliding Head + ) High Fall + Rise ( + Tail)

(Low Pre-Head + ) (Scandent Head + ) Low Fall (+ Tail)

(Low Pre-Head + ) (Scandent Head + ) High Fall (+ Tail)

The speed of utterance of reading scientific prose fluctuates from normal to accelerated, but it is never too fast. This can be explained by the greater length of words and the greater number of stressed syllables within an intonation group. Variations in speed also depend on the communicative centre. Since a communicative centre is brought out by slowing down the speed of utterance and less important words in the intonation group are pronounced at greater speed, the general speed of utterance is perceived as accelerated.

Reading scientific prose is characterized by contrastive rhythmic patterns. This is predetermined by the correlation of rhythm and speed of utterance. It is generally known that slow speed entails regular rhythm while in accelerated speech rhythm is less regular. Pauses are predominantly short, their placement and internal boundaries are always semantically or syntactically predictable. Hesitation pauses are to be avoided.

The following examples serve as a model of scientific style.

Declamatory Style

In declamatory style the emotional role of intonation increases, thereby intonation patterns used for intellectual, volitional and emotional purposes have an equal share. This style comprises two varieties of oral representation of written literary texts, namely: reading aloud a piece of descriptive prose (the author’s speech) and the author’s reproduction of actual conversation (the speech of characters). The speaker’s aim is to appeal simultaneously to the mind, the will and feelings of the listener by image-bearing devices.

Declamatory style is generally acquired by special training and it is used, for example, in stage speech, classroom recitation, verse speaking or in reading aloud fiction. The intonation of reading descriptive prose has many features in common with that of reading scientific prose. In both styles the same set of intonation means is made use of, but the frequency of their occurrence is different here.

In the pre-nuclear part the Low Pre-Head may be combined with the Stepping Head, the broken Stepping Head, or a descending sequence of syllables interrupted by several falls. It is interesting to note that the Scandent Head is not found in reading descriptive prose, it is confined to scientific prose. The nuclear tone in final intonation groups is generally the Low Fall, or, less frequently, the High Fall. This is due to the fact that both in scientific and descriptive prose the prevailing sentence type is declarative, necessitating the use of the falling tone. The principal nuclear tones in non-final intonation groups are the Low Fall, the High Fall and the Fall-Rise. The simple tunes are more frequent in descriptive texts while the compound tunes are more typical of scientific texts.

When reading aloud a dialogic text it should be borne in mind that the intonation representing speech of the characters is always stylized. As far as the pre-nuclear pattern is concerned, it should be noted that the Low or High Pre-Head may be combined with any variety of descending, ascending or level heads. In the terminal tone both simple and compound tunes are widely used. Special mention should be made of the falling-rising tone which has a greater frequency of occurrence in reading dialogic texts than in actual situation. The overall speed of utterance in reading is normal or reduced as compared with natural speech, and as a result the rhythm is more even and regular. Pauses are either connecting or disjunctive, thereby internal boundaries placement is always semantically or syntactically predictable. Hesitation pauses do not occur, unless they are deliberately used for stylization purposes.

To select an intonation pattern for a particular utterance one has to take into account the author’s suggestion as to how the text should be read (eg. the playwright’s remarks, and stage directions in drama). Moreover, one has to consider the character’s social and educational background, the kind of relationship existing between him and other characters as well as the extra-linguistic context at large.

Publicistic Style

The term ‘publicistic style’ is a very broad label, which covers a variety of types, distinguishable on the basis of the speaker’s occupation, situation and purpose. Publicistic style is characterized by predominance of volitional intonation patterns against the background of intellectual and emotional ones. The general aim of this intonational style is to exert influence on the listener, to convince him that the speaker’s interpretation is the only correct one and to cause him to accept the point of view expressed in the speech. The task is accomplished not merely through logical argumentation but through persuasion and emotional appeal. For this reason publicistic style has features in common with scientific style, on the one hand, and declamatory style, one the other. As distinct from the latter its persuasive and emotional appeal is achieved not by the use of imaginary but in a more direct manner.

Publicistic style is made resort to by political speech-makers, radio and television commentators, participants of press conferences and interviews, counsel and judges in courts of law. It is the type of public speaking dealing with political and social problems (eg. parliamentary debates, speeches at rallies, congresses, meeting and election campaigns).

Any kind of oration imposes some very important constraints on the speaker. Normally, it is the written variety of English that is being used (a speech may be written out in full and rehearsed). The success of a political speech-maker is largely dependent on his ability to manipulate intonation and voice quality. In accordance with his primary desire to convince the listeners of his merits he also has to ensure a well-defined ideas combined with persuasive and emotional appeal.

The intonation adequate for political speeches is characterized by the following regularities. In the pre-nuclear part the main patterns are: (Low Pre-Head +) Stepping Head; (Low Pre-Head +) Falling Head. The heads are often broken due to extensive use of accidental rises to make an utterance more emphatic. The High Level Head is less frequent and the Low Level Head here is indicative of tonal subordination. By tonal subordination we refer to cases when the pitch-level of an intonation group is dependent on its neighbours, semantically and communicatively more important intonation groups being pronounced on a higher pitch-level. The nuclear tone of final intonation groups is generally the Low Fall; the High Fall is much less common. In non-final intonation groups both simple and compound tunes are found, namely, the Low Fall, the Low Rise, the Mid-level and the Fall-Rise. The High Fall and the High Rise are very rarely used for purposes of intra-phrasal coordination. It is interesting to note that the Low Rise and the Mid-level tones are typical of more formal discourse, whereas the Fall-Rise is typical of less formal and more fluent discourse.

The speed of utterance is related to the degree of formality, the convention being that formal speech is usually slow, and less formal situations entail acceleration of speed. Variations in rhythm are few. Pauses and the ensuing internal boundaries are explicable in semantic and syntactic terms. Intonation groups tend to be short and as a result pauses are numerous, ranging from brief to very long. Hesitation pauses are avoided, still silent hesitation pauses occasionally do occur. It is interesting to note that some of the best ripostes during a political speech come at a point when the speaker is trying to gain maximum effect through a rhetorical silence. Moreover, an utterance is often emphasized by means of increased sentence-stress and the glottal stop.

This extract from a political speech may serve as an example of publicistic style.

Дата добавления: 2021-01-20; просмотров: 1008; Мы поможем в написании вашей работы! |

Мы поможем в написании ваших работ!