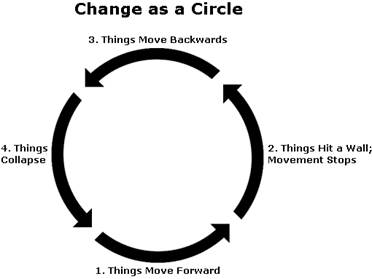

Figure 2 : Change as a Circle

At other times we feel as if we have reached an impasse. A wall has been erected that blocks and stops everything.

Then there are times when the change processes seem to be going backwards. We feel as if what has been achieved is now being undone. We hear language like, “In a single stroke, years of work have been set back.” We experience “swimming against the tide” or “heading upstream.” These metaphors underscore the reality that change—even positive change—includes periods of going backward as much as going forward.

Then there are times when we feel as though we are living through a complete breakdown. Things are not just retrogressing. Instead, they are coming apart, collapsing like a building falling. In the ebb and flow of conflict and peacebuilding we experience these periods as deeply depressing, often accompanied by a phrase such as, “We have to start from ground zero.”

All these experiences, though not always in the same chronological order, are normal parts of the change circle. Understanding change as circular helps us to know and anticipate this. The circle recognizes that no one point in time determines the broader pattern. Rather, change encompasses different sets of patterns and directions as part of the whole.

The circle cautions us at each step: going forward too quickly may not be wise. Meeting an obstacle probably provides a useful reality check. Going backward may create more innovative ways forward. And coming down may create opportunities to build in wholly new ways.

At every step, circular thinking makes a practical appeal: Look. See. Adapt. It reminds us that change, like life, is never static. This is the circle portion of a dynamic process-structure.

The linear quality of change, on the other hand, means that things move from one point to the next. In mathematics, a line is the shortest route between two points. It is straight with no contours or detours. A linear orientation is associated with rational thinking, understanding things purely in terms of logical cause and effect. So how does this relate to that characteristic of change which we have just described as not one-directional or not logical in a pure sense? Recognizing the linear nature of change requires us to think about its overall direction and purpose. It is another—and essential—way of seeing the web of patterns of different factors relating and moving toward making a whole.

|

|

|

A linear view suggests that social forces move in broad directions, not usually visible to the naked eye, rarely obvious in short time frames. A linear perspective asks us to stand back and take a look at the overall direction of social conflict and the change we seek that includes history and future. Specifically, it requires us to look at the pattern of circles, not just the immediate experience.

Change as process-structure

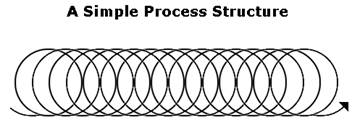

Figure 3 graphically displays a simple process-structure. This picture holds together a web of dynamic circles creating an overall momentum and direction. Some might refer to this as a rotini, a spiral made up of multidirectional internal patterns that create a common overall movement.

Figure 3 : A Simple Process-Structure

In the scientific community, opponents of linear thinking argue that linearity assumes a deterministic view of change which discourages our ability to predict and control outcomes. While this is a useful warning, I do not believe that a lack of control and determinism are incompatible with purpose and orientation. We have to seek “our North,” as the Spanish would say; we must articulate how we think change actually happens and what direction it is going. This is the gift of seeing in a linear fashion: it requires us to articulate how we think things are related, how movement is created, and in what overall direction things are flowing. In other words, a linear approach pushes us to express and test our theories of change that too often lie unexplored and dormant beneath layers of rhetoric and our kneejerk responses and actions. Linear thinking says, “Hey, good intentions are not enough. How exactly is this action creating change? What is changing and in what direction is it going?” The key to creating a platform for transformation in the midst of conflict lies in holding together a healthy dose of both circular and linear perspectives.

Transformational platforms

A transformational approach requires us to build an ongoing and adaptive base at the epicenter of conflict, a “platform.” A platform is like a scaffold-trampoline: it gives a base to stand on and jump from. The platform includes an understanding of the various levels of the conflict (the “big picture”), processes for addressing immediate problems and conflicts, a vision for the future, and a plan for change processes which will move in that direction. From this base it becomes possible to generate processes that create solutions to short-term needs and, at the same time, work on strategic, long-term, constructive change in systems and relationships.

|

|

|

Дата добавления: 2019-02-13; просмотров: 246; Мы поможем в написании вашей работы! |

Мы поможем в написании ваших работ!