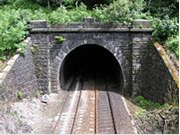

Totley Tunnel on the Manchester to Sheffield line

Dany by: Chernyshova Nastya

From

Teacher: Kestel O. V.

Semey 2009

Content

1. Introduction

2. Dartmoor National park

History

Pre-history

Beardown Man, Dartmoor

The historical period

Myths and literature

Towns

Physical geography

Rivers

3. Peak district national park

History

Early history

Medieval to modern history

Transport

History

Totley Tunnel on the Manchester to Sheffield line

Road network

Public transport

Geography

4. The Broads National Park

History

Geography

5. Queen Elizabeth Park, British Columbia

History

Attractions

6. History of the New Forest

New Forest National Park

Geography

7. Exmoor

History

Geology

Coastline

Flora

Fauna

Places of interest

8. Yorkshire Dales

Yorkshire Dales National Park

Geography

Cave systems

9. Lake District

General geography

Development of tourism

Conclusion

Additional material

Literature

Introduction

The theam of my project work “National parks of Great Britan".

National Parks of Great Britan cover approximately 7% of the country. They did not have any special exotic animals or plants, But such areas as Dartmoor, Peak District, Yorkshire, Valley Noth York, the New Forest and Broads every year attract thousends of tourists. The peculiarity of the British National parks in that it isn’t “dead" area, And quite close to major urban areas, which allowed any activity aimed at restoration of nature, so most of the National psrks are more like the great urban parks or botanical gardens. Many of them - private ownership.

In my project work, I will write about some of them.

Special attention I wiil pay to the study of history, culture and geography.

Dartmoor National park

Dartmoor is an area of moorland in the centre of Devon, England. Protected by National Park status, it covers 368 square miles (953 km2).

The granite upland dates from the Carboniferous period of geological history. The moorland is capped with many exposed granite hilltops (known as tors), providing habitats for Dartmoor wildlife. The highest point is High Willhays, 621 m (2,037 ft) above sea level. The entire area is rich in antiquities and archaeology.

Dartmoor is managed by the Dartmoor National Park Authority whose 26 members are drawn from Devon County Council, local District Councils and Government.

|

|

|

Parts of Dartmoor have been used as a military firing range for over two hundred years. The public enjoy extensive access rights to the rest of Dartmoor, and it is a popular tourist destination. The Park was featured on the TV programme Seven Natural Wonders as the top natural wonder in South West England.

History

Pre-history

The majority of the prehistoric remains on Dartmoor date back to the late Neolithic and early Bronze Age. Indeed, Dartmoor contains the largest concentration of Bronze Age remains in the United Kingdom, which suggests that this was when a larger population moved onto the hills of Dartmoor.

The climate at the time was warmer than today, and much of today’s moorland was covered with trees. The prehistoric settlers began clearing the forest, and established the first farming communities. Fire was the main method of clearing land, creating pasture and swidden types of fire-fallow farmland. Areas less suited for farming, tended to be burned for livestock grazing. Over the centuries these Neolithic practices greatly expanded the upland moors, contributed to the acidification of the soil and the accumulation of peat and bogs.

The nature of the soil, which is highly acidic, means that no organic remains have survived. However, by contrast, the high durability of the natural granite means that their homes and monuments are still to be found in abundance, as are their flint tools. It should be noted that a number of remains were “restored" by enthusiastic Victorians and that, in some cases, they have placed their own interpretation on how an area may have looked.

Beardown Man, Dartmoor

Numerous menhirs (more usually referred to locally as standing stones or longstones), stone circles, kistvaens, cairns and stone rows are to be found on the moor. The most significant sites include:

Beardown Man, near Devil’s Tor - isolated standing stone 3.5 m (11 ft) high, said to have another 1 m (3.3 ft) below ground. grid reference SX596796

Challacombe, near the prehistoric settlement of Grimspound - triple stone row. grid reference SX689807

|

|

|

Drizzlecombe, east of Sheepstor village - stone circles, rows, standing stones, kistvaens and cairns. grid reference SX591669

Grey Wethers, near Postbridge - double circle, aligned almost exactly north south. grid reference SX638831

Laughter Tor, near Two Bridges - standing stone 2.4 m (7.9 ft) high and two double stone rows, one 164 m (540 ft) long. grid reference SX652753

Merrivale, between Princetown and Tavistock - includes a double stone row 182 m (600 ft) long, 1.1 m (3.6 ft) wide, aligned almost exactly east-west), stone circles and a kistvaen. grid reference SX554747

Scorhill, west of Chagford - circle, 26.8 m (88 ft) in circumference, and stone rows. grid reference SX654873

Shovel Down, north of Fernworthy reservoir - double stone row approximately 120 m (390 ft) long. grid reference SX660859

There are also an estimated 5,000 hut circles still surviving today, despite the fact that many have been raided over the centuries by the builders of the traditional dry stone walls. These are the remnants of Bronze Age houses. The smallest are around 1.8 m (6 ft) in diameter, and the largest may be up to five times this size.

Some have L-shaped porches to protect against wind and rain - some particularly good examples are to be found at Grimspound. It is believed that they would have had a conical roof, supported by timbers and covered in turf or thatch.

Many ancient structures, including the hut circles at Grimspound, were reconstructed during the 19th century - most notably by civil engineer and historian Richard Hansford Worth. Some of this work was based more on speculation than archaeological expertise, and has since been criticised for its inaccuracy.

The historical period

The climate worsened over the course of a thousand years from around 1000 BC, so that much of high Dartmoor was largely abandoned by its early inhabitants.

It was not until the early medieval period that the weather again became warmer, and settlers moved back onto the moors. Like their ancient forebears, they also used the natural granite to build their homes, preferring a style known as the longhouse - some of which are still inhabited today, although they have been clearly adapted over the centuries. Many are now being used as farm buildings, while others were abandoned and fell into ruin.

|

|

|

The earliest surviving farms, still in operation today, are known as the Ancient Tenements. Most of these date back to the 14th century and sometimes earlier.

Some way into the moor stands the town of Princetown, the site of the notorious Dartmoor Prison, which was originally built both by, and for, prisoners of war from the Napoleonic Wars. The prison has a (now misplaced) reputation for being escape-proof, both due to the buildings themselves and its physical location.

The Dartmoor landscape is scattered with the marks left by the many generations who have lived and worked there over the centuries - such as the remains of the once mighty Dartmoor tin-mining industry, and farmhouses long since abandoned. Indeed the industrial archaeology of Dartmoor is a subject in its own right.

Myths and literature

Dartmoor abounds with myths and legends. It is reputedly the haunt of pixies, a headless horseman, a mysterious pack of ‘spectral hounds’, and a large black dog. During the Great Thunderstorm of 1638, Dartmoor was even said to have been visited by the Devil.

Many landmarks have ancient legends and ghost stories associated with them, such as Jay’s Grave, the ancient burial site at Childe’s Tomb, the rock pile called Bowerman’s Nose, and the stone crosses that mark mediaeval routes across the moor.

A few stories have emerged in recent decades, such as the ‘hairy hands’, that are said to attack travellers on the B3212 near Two Bridges.

Dartmoor has inspired a number of artists and writers, such as Sir Arthur Conan Doyle in The Hound of the Baskervilles and The Adventure of Silver Blaze, Eden Phillpotts, Beatrice Chase, Agatha Christie and the Reverend Sabine Baring-Gould.

Towns

and villages

Dartmoor has a resident population of about 33,400, which swells considerably during holiday periods with incoming tourists. For a list, expand the Settlements of Dartmoor navigational box at the bottom of this page.

|

|

|

Physical geography

Tors.

Dartmoor is known for its tors - large hills, topped with outcrops of bedrock, which in granite country such as this are usually rounded boulder-like formations. There are over 160 tors on Dartmoor. They are the focus of an annual event known as the Ten Tors Challenge, when over a thousand people, aged between 14 and 21, walk for distances of 35, 45 or 55 miles (56, 72 or 89 km) over ten tors on many differing routes. While many of the hills of Dartmoor have the word “Tor” in them quite a number do not, however this does not appear to relate to whether there is an outcrop of rock on their summit.

The highest points on Dartmoor are High Willhays (grid reference SX580895) at 621 m (2,040 ft) and Yes Tor (grid reference SX581901) 619 m (2,030 ft) on the northern moor. Ryder’s Hill (grid reference SX690660), 515 m (1,690 ft), Snowdon 495 m (1,620 ft), and an unnamed point at (grid reference SX603645),493 m (1,620 ft) are the highest points on the southern moor. Probably the best known tor on Dartmoor is Haytor (also spelt Hey Tor) (grid reference SX757771), 457 m (1,500 ft). For a more complete list see List of Dartmoor tors and hills.

Rivers

The levels of rainfall on Dartmoor are considerably higher than in the surrounding lowlands. With much of the national park covered in thick layers of peat, the rain is usually absorbed quickly and distributed slowly, so that the moor is rarely dry.

In areas where water accumulates, dangerous bogs or mires can result. Some of these, up to 12 feet (3.7 m) across and topped with bright green moss, are known to locals as “feather beds” or “quakers", because they shift (or ‘quake’) beneath your feet. This is the result of accumulations of sphagnum moss growing over a hollow in the granite filled with water.

Another consequence of the high rainfall is that there are numerous rivers and streams on Dartmoor. As well as shaping the landscape, these have traditionally provided a source of power for moor industries such as tin mining and quarrying.

The Moor takes its name from the River Dart, which starts as the East Dart and West Dart and then becomes a single river at Dartmeet.

For a full list, expand the Rivers of Dartmoor navigational box at the bottom of this page.

Angling.

Angling is a popular pastime on the moor, especially for migratory fish such as salmon.

Kayaking and canoeing.

Dartmoor is a focal point for whitewater kayaking and canoeing, due to the previously mentioned high rainfall and high quality of rivers. The River Dart is the most prominent meeting place, the section known as the Loop being particularly popular, but the Erme, Plym, Tavy and Teign are also frequently paddled. There are other rivers on the moor which can be paddled, including the Walkham and Bovey. The access situation is variable on Dartmoor, some paddlers have experienced difficulties with landowners, while others have had a friendly reception.

Peak district national park

The Peak District is an upland area in central and northern England, lying mainly in northern Derbyshire, but also covering parts of Cheshire, Greater Manchester, Staffordshire, and South and West Yorkshire.

Most of the area falls within the Peak District National Park, whose designation in 1951 made it the earliest national park in the British Isles. An area of great diversity, it is conventionally split into the northern Dark Peak, where most of the moorland is found and whose geology is gritstone, and the southern White Peak, where most of the population lives and where the geology is mainly limestone-based. Proximity to the major cities of Manchester and Sheffield and the counties of Yorkshire, Lancashire, Greater Manchester, Cheshire and Staffordshire coupled with easy access by road and rail, have all contributed to its popularity. With an estimated 22 million visitors per year, the Peak District is thought to be the second most-visited national park in the world (after the Mount Fuji National Park in Japan).

History

Early history

The Peak District has been settled from the earliest periods of human activity, as is evidenced by occasional finds of Mesolithic flint artefacts and by palaeoenvironmental evidence from caves in Dovedale and elsewhere. There is also evidence of Neolithic activity, including some monumental earthworks or barrows (burial mounds) such as that at Margery Hill. [12] In the Bronze Age the area was well populated and farmed, and evidence of these people survives in henges such as Arbor Low near Youlgreave or the Nine Ladies Stone Circle at Stanton Moor. In the same period, and on into the Iron Age, a number of significant hillforts such as that at Mam Tor were created. Roman occupation was sparse but the Romans certainly exploited the rich mineral veins of the area, exporting lead from the Buxton area along well-used routes. There were Roman settlements, including one at Buxton which was known to them as “Aquae Arnemetiae” in recognition of its spring, dedicated to the local goddess.

Theories as to the derivation of the Peak District name include the idea that it came from the Pecsaetan or peaklanders, an Anglo-Saxon tribe who inhabited the central and northern parts of the area from the 6th century AD when it fell within the large Anglian kingdom of Mercia.

Medieval to modern history

In medieval and early modern times the land was mainly agricultural, as it still is today, with sheep farming, rather than arable, the main activity in these upland holdings. However, from the 16th century onwards the mineral and geological wealth of the Peak became increasingly significant. Not only lead, but also coal, copper (at Ecton), zinc, iron, manganese and silver have all been mined here. Celia Fiennes, describing her journey through the Peak in 1697, wrote of ‘those craggy hills whose bowells are full of mines of all kinds off black and white and veined marbles, and some have mines of copper, others tinn and leaden mines, in w [hi] ch is a great deale of silver. ’ Lead mining peaked in the 17th and 18th centuries and began to decline from the mid-19th century, with the last major mine closing in 1939, though lead remains a by-product of fluorspar, baryte and calcite mining (see Derbyshire lead mining history for details). Limestone and gritstone quarries flourished as lead mining declined, and remain an important industry in the Peak.

Large reservoirs such as Woodhead and Howden were built from the late 19th century onward to supply the growing urban areas surrounding the Peak District, often flooding large areas of farmland and depopulating the surrounding land in an attempt to improve the water purity.

The northern moors of Saddleworth and Wessenden gained notoriety in the 1960s as the burial site of several children murdered by the so-called Moors Murderers, Ian Brady and Myra Hindley.

Transport

History

The first roads in the Peak were constructed by the Romans, although they may have followed existing tracks. The Roman network is thought to have linked the settlements and forts of Aquae Arnemetiae (Buxton), Chesterfield, Ardotalia (Glossop) and Navio (Brough-on-Noe), and extended outwards to Danum (Doncaster), Manucium (Manchester) and Derventio (Little Chester, near Derby). Parts of the modern A515 and A53 roads south of Buxton are believed to run along Roman roads.

Packhorse routes criss-crossed the Peak in the Medieval era, and some paved causeways are believed to date from this period, such as the Long Causeway along Stanage. However, no highways were marked on Saxton’s map of Derbyshire, published in 1579. Bridge-building improved the transport network; a surviving early example is the three-arched gritstone bridge over the River Derwent at Baslow, which dates from 1608 and has an adjacent toll-shelter. [18] Although the introduction of turnpike roads (toll roads) from 1731 reduced journey times, the journey from Sheffield to Manchester in 1800 still took 16 hours, prompting Samuel Taylor Coleridge to remark that ‘a tortoise could outgallop us! ’From around 1815 onwards, turnpike roads both increased in length and improved in quality. An example is the Snake Road, built under the direction of Thomas Telford in 1819-21 (now the A57); the name refers to the crest of the Dukes of Devonshire. The Cromford Canal opened in 1794, carrying coal, lead and iron ore to the Erewash Canal.

Totley Tunnel on the Manchester to Sheffield line

The improved roads and the Cromford Canal both shortly came under competition from new railways, with work on the first railway in the Peak commencing in 1825. Although the Cromford and High Peak Railway (from Cromford Canal to Whaley Bridge) was an industrial railway, passenger services soon followed, including the Woodhead Line (Sheffield to Manchester via Longdendale) and the Manchester, Buxton, Matlock and Midlands Junction Railway. Not everyone regarded the railways as an improvement. John Ruskin wrote of the Monsal Dale line: ‘You enterprised a railroad through the valley, you blasted its rocks away, heaped thousands of tons of shale into its lovely stream. The valley is gone, and the gods with it; and now, every fool in Buxton can be at Bakewell in half-an-hour, and every fool in Bakewell at Buxton.

By the second half of the 20th century, the pendulum had swung back towards road transport. The Cromford Canal was largely abandoned in 1944, and several of the rail lines passing through the Peak were closed as uneconomic in the 1960s as part of the Beeching Axe. The Woodhead Line was closed between Hadfield and Penistone; parts of the trackbed are now used for the Trans-Pennine Trail, the stretch between Hadfield and Woodhead being known specifically as the Longdendale Trail. The Manchester, Buxton, Matlock and Midlands Junction Railway is now closed between Rowsley and Buxton where the trackbed forms part of the Monsal Trail. The Cromford and High Peak Railway is now completely shut, with part of the trackbed open to the public as the High Peak Trail. Another disused rail line between Buxton and Ashbourne now forms the Tissington Trail.

Road network

The main roads through the Peak District are the A57 (Snake Pass) between Sheffield and Manchester, the A628 (Woodhead Pass) between Barnsley and Manchester via Longdendale, the A6 from Derby to Manchester via Buxton, and the Cat and Fiddle road from Macclesfield to Buxton. These roads, and the pretty minor roads and lanes, are attractive to drivers, but the Peak’s popularity makes road congestion a significant problem especially during summer.

Public transport

The Peak District is readily accessible by public transport, which reaches even central areas. Train services into the area are the Hope Valley Line from Sheffield and Manchester; the Derwent Valley Line from Derby to Matlock; and the Buxton Line and the Glossop Line linking those towns to Manchester. Coach (long-distance bus) services provide access to Matlock, Bakewell and Buxton from Derby, Nottingham and Manchester, and there are regular buses from the nearest towns such as Sheffield, Glossop, Stoke, Leek and Chesterfield. The nearest airports are Manchester, East Midlands and Doncaster-Sheffield.

For such a rural area, the smaller villages of the Peak are relatively well served by internal transport links. There are many minibuses operating from the main towns (Bakewell, Matlock, Hathersage, Castleton, Tideswell and Ashbourne) out to the small villages. The Hope Valley and Buxton Line trains also serves many local stations (including Hathersage, Hope and Edale).

Geography

The Peak District forms the southern end of the Pennines and much of the area is uplands above 1,000 feet (300 m), with a high point on Kinder Scout of 2,087 feet (636 m). Despite its name, the landscape lacks sharp peaks, being characterised by rounded hills and gritstone escarpments (the “edges”). The area is surrounded by major conurbations, including Huddersfield, Manchester, Sheffield, Derby and Stoke-on-Trent.

The National Park covers 555 square miles (1,440 km2) of Derbyshire, Staffordshire, Cheshire, Greater Manchester and South and West Yorkshire, including the majority of the area commonly referred to as the Peak. The Park boundaries were drawn to exclude large built-up areas and industrial sites from the park; in particular, the town of Buxton and the adjacent quarries are located at the end of the Peak Dale corridor, surrounded on three sides by the Park. The town of Bakewell and numerous villages are, however, included within the boundaries, as is much of the (non-industrial) west of Sheffield. As of 2006, it is the fourth largest National Park in England and Wales. As always in Britain, the designation “National Park” means that there are planning restrictions to protect the area from inappropriate development, and a Park Authority to look after it-but does not imply that the land is owned by the government, or is uninhabited.

High Peak panorama between Hayfield and Chinley

12% of the Peak District National Park is owned by the National Trust, a charity which aims to conserve historic and natural landscapes. It does not receive government funding. The three Trust estates (High Peak, South Peak and Longshaw) include the ecologically or geologically significant areas of Bleaklow, Derwent Edge, Hope Woodlands, Kinder Scout, Leek and Manifold, Mam Tor, Dovedale, Milldale and Winnats Pass. The Peak District National Park Authority directly owns around 5%, and other major landowners include several water companies.

The Broads National Park

The Broads is a network of mostly navigable rivers and lakes (known locally as broads) in the English counties of Norfolk and Suffolk. The Broads, and some surrounding land was constituted as a special area with a level of protection similar to a UK National Park by The Norfolk and Suffolk Broads Act of 1988. The Broads Authority, a Special Statutory Authority responsible for managing the area, became operational in 1989

The total area is 303 km² (188 sq.miles), most of which is in Norfolk, with over 200 km (125 miles) of navigable waterways. There are seven rivers and sixty three broads, mostly less than twelve feet deep. Thirteen broads are generally open to navigation, with a further three having navigable channels. Some broads have navigation restrictions imposed on them in autumn and winter.

Although the terms Norfolk Broads and Suffolk Broads are used to identify those areas within the two counties respectively, the whole area is sometimes referred to as the “Norfolk Broads”. The Broads has the same status as the national parks in England and Wales but as well as the Broads Authority having powers and duties almost identical to the national parks it is also the third largest inland navigation authority. Because of its navigation role the Broads Authority was established under its own legislation on 1 April 1989. More recently the Authority wanted to change the name of the area to The Broads National Park in recognition of the fact that the status of the area is equivalent to the rest of the national park family but was unable to get agreement from all the different parties. The Private Bill the Authority is promoting through Parliament is largely about improving public safety on the water and the Authority did not want to delay or jeopardise these provisions for the name issue, so the provision was dropped before the Bill was deposited in Parliament.

History

For many years the broads were regarded as natural features of the landscape. It was only in the 1960s that Dr Joyce Lambert proved that they were artificial features, the effect of flooding on early peat excavations. The Romans first exploited the rich peat beds of the area for fuel, and in the Middle Ages the local monasteries began to excavate the peat lands as a turbary business, selling fuel to Norwich and Great Yarmouth. The Cathedral took 320,000 tonnes of peat a year. Then the sea levels began to rise, and the pits began to flood. Despite the construction of windpumps and dykes, the flooding continued and resulted in the typical Broads landscape of today, with its reed beds, grazing marshes and wet woodland.

The Broads have been a favourite boating holiday destination since the early 20th century. The waterways are lock-free, although there are three bridges under which only small cruisers can pass. The area attracts all kinds of visitors, including ramblers, artists, anglers, and bird-watchers as well as people “messing about in boats". There are a number of companies hiring boats for leisure use, including both yachts and motor launches. The Norfolk Wherry, the traditional cargo craft of the area, can still be seen on the Broads as some specimens have been preserved and restored.

Ted Ellis, a local naturalist, referred to the Broads as “the breathing space for the cure of souls”.

A great variety of boats can be found on the Broads, from Edwardian trading wherries to state-of-the-art electric or solar-powered boats.

Geography

The point at which the River Yare and the River Waveney merge into Breydon Water

Yachts on the Norfolk Broads

How Hill

St. Benet’s Abbey

The Broads largely follows the line of the rivers and natural navigations of the area. There are seven navigable rivers, the River Yare and its (direct and indirect) tributaries the Rivers Bure, Thurne, Ant, Waveney, Chet and Wensum. There are no locks on any of the rivers (except for Mutford lock in Oulton Broad that links to the saltwater Lake Lothing in Lowestoft), all the waterways are subject to tidal influence. The tidal range decreases with distance from the sea, with highly tidal areas such as Breydon Water contrasted with effectively non-tidal reaches such as the River Ant upstream of Barton Broad.

The broads themselves range in size from small pools to the large expanses of Hickling Broad, Barton Broad and Breydon Water. The broads are unevenly distributed, with far more broads in the northern half of Broadland (the Rivers Bure, Thurne and Ant) than in the central and southern portions (the Rivers Yare, Waveney, Chet and Wensum). Individual broads may lie directly on the river, or are more often situated to one side and connected to the river by an artificial channel or dyke.

Besides the natural watercourses of the rivers, and the ancient but artificial broads, there is one more recent navigation canal, the lock-less New Cut which connects the Rivers Yare and Waveney whilst permitting boats to by-pass Breydon Water.

There is also a second navigable link to the sea, via the River Waveney and its link to Oulton Broad. Oulton Broad is part of the Broads tidal system, but is immediately adjacent to Lake Lothing which is itself directly connected to the sea via the harbour at Lowestoft. Oulton Broad and Lake Lothing are connected by Mutford Lock, the only lock on the broads and necessary because of the different tidal ranges and cycles in the two lakes.

In the lists below, names of broads are emboldened to help distinguish them from towns and villages.

Дата добавления: 2019-11-16; просмотров: 186; Мы поможем в написании вашей работы! |

Мы поможем в написании ваших работ!