Collocationally or colligationally conditioned

The development of polysemy. Meaning and context.

Meaning -reverberation (отражение) in the human consciousness of an object of extra-linguistic reality (a phenomenon a relationship, a quality, a process) which becomes fact of language because of its constant indissoluble |ˌɪndɪˈsɒljʊb(ə)l| association with a definite linguistic expression.

Polysemy– diversity of meanings, existence within one word of several connected meanings as the result of the development and changes of its original meaning.

Lexical meaning – the material meaning of a word as distinct from its formal grammatical meaning, which reflects the concept the word expresses.

Grammatical meaning – the meaning of the formal membership of word in the grammatical system of a language (is expressed in the word’s form)

The very function of the word as a unit of communication is made possible by its possessing a meaning. Therefore, among the word's various characteristics, meaning is certainly the most important.

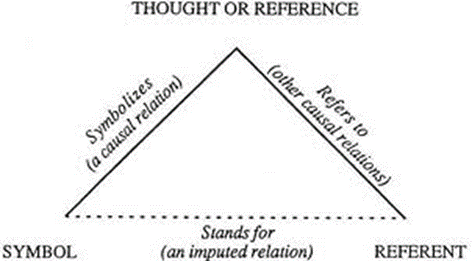

Meaningcan be more or less described as a component of the word through which a concept is communicated, in this way endowing the word with the ability of denoting real objects, qualities, actions and abstract notions. The complex and somewhat mysterious relationships between referent (object, etc. denoted by the word), concept and word are traditionally represented by the following triangle (by Ogden and Richards):

By the "symbol" here is meant the word; thought or reference is concept. The dotted line suggests that there is no immediate relation between word and referent: it is established only through the concept.Concept– a generalized reverberation (отражение) in the human consciousness of the properties of objective reality.

This can be easily proved by comparing the sound-forms of different languages conveying one and the same meaning, e.g. English [d^v], Russian [golub'], German [taube] and so on. It can also be proved by comparing almost identical sound-forms that possess different meaning in different languages. The sound-cluster [kot], e.g. in the English language means ‘a small, usually swinging bed for a child’, but in the Russian language essentially the same sound-cluster possesses the meaning ‘male cat’.

The branch of linguistics which specialises in the study of meaning is called semantics.

The modern approach to semantics is based on the assumption that the inner form of the word (i. e. its meaning) presents a structure which is called the semantic structure of the word.

The semantic structure of the word does not present an indissoluble|ˌɪndɪˈsɒljʊb(ə)l| unity, nor does it necessarily stand for one concept. It is generally known that most words convey several concepts and thus possess the corresponding number of meanings. A word having several meanings is called polysemantic, and the ability of words to have more than one meaning is described by the termpolysemy (monosemantic words, i.e. words having only one meaning, are comparatively few in number; they are mainly scientific terms such as molecule, hydrogen and the like).

Polysemy is certainly not an anomaly. Most English words are polysemantic. It should be noted that the wealth of expressive resources of a language largely depends on the degree to which polysemy has developed in the language. It also should be pointed out that the number of sound combinations that human speech organs can produce is limited. So, at a certain stage of language development the production of new words by morphological means becomes limited, and polysemy becomes increasingly important in providing the means for enriching the vocabulary. From this, it should be clear that the process of enriching the vocabulary does not consist merely in adding new words to it, but, also, in the constant development of polysemy.

The system of meanings of any polysemantic word develops gradually, mostly over the centuries, as more and more new meanings are either added to old ones, or oust some of them. So the complicated processes of polysemy development involve both the appearance of new meanings and the loss of old ones. Yet, the general tendency with English vocabulary at the modern stage of its history is to increase the total number of its meanings and in this way to provide for a quantitative and qualitative growth of the language's expressive resources.(Антрушина)

One of the most important "drawbacks" of polysemantic words is that there is sometimes a chance of misunderstanding when a word is used in a certain meaning but accepted by a listener or reader in another. This situation may happen in a bookshop:

Customer: I would like a book, please.

Bookseller: Something light?

Customer: That doesn't matter. I have my car with me.

Generally speaking, it is common knowledge that context is a powerful preventative against any misunderstanding of meanings. For instance, the adjective dull, if used out of context, would mean different things to different people or nothing at all. It is only in combination with other words that it reveals its actual meaning: a dull pupil, a dull play, dull weather, etc.

Current research in semantics is largely based on the assumption that one of the more promising methods of investigating the semantic structure of a word is by studying the word's linear relationships with other words in typical contexts, i. e. its combinability or collocability.

Context– a) linguistic environment of a unit of language which reveals the conditions and the characteristic features of it usage in speech; b) semantically complete passage of written speech sufficient to establish the meaning of a given word (phrase); c) context of situation, the extralinguistic situation which enables (позволяет) understand the meaning of a word or phrase.

Context is a good and reliable key to the meaning of the word.And here we are faced withtwo dangers. The first is that of sheer misunderstanding, when the speaker means one thing and the listener takes the word in its other meaning.

The second danger has nothing to do with the process of communication but with research work in the field of semantics. A common error with the inexperienced research worker is to see a different meaning in every new set of combinations. Here is a puzzling question to illustrate what we mean. Cf.: an angry man, an angry letter. Is the adjective angry used in the same meaning in both these contexts or in two different meanings? Some people will say "two" and argue that, on the one hand, the combinability is different (man — name of person; letter — name of object) and, on the other hand, a letter cannot experience anger. True, it cannot; but it can very well convey the anger of the person who wrote it. As to the combinability, the main point is that a word can realise the same meaning in different sets of combinability. For instance, in the pairs merry children, merry laughter, merry faces, merry songs the adjective merry conveys the same concept of high spirits whether they are directly experienced by the children (in the first phrase) or indirectly expressed through the merry faces, the laughter and the songs of the other word groups.

The task of distinguishing between the different meanings of a word and the different variations of combinability (or, in a tradition-al terminology, different usages of the word) is actually a question of singling out the different denotations within the semantic structure of the word.

Cf.: 1) a sad woman,

2) a sad voice,

3) a sad story,

4) a sad scoundrel (= an incorrigible scoundrel)

5) a sad night (= a dark, black night, arch, poet.)

According to Vinogradov’s theory of semantic structure a polysemantic word may have the following types of meanings:

1) ‘Nominative (de’notative). The basic meaning of the word which refers to objects of extralinguistic reality in a direct and straightforward way, reflecting their actual relations. (e.g. Fox – an animal with red fur).

Main characterictics:

- easily translatable;

- frequent in usage;

- stylistically neutral;

- belong to the general word stock of the language.

2) ‘Nominative – de’rivative (‘conno’tative). Other meanings in a polysemantic word which are characterized by free combinality and are connected with the main nominative meaning. Comes into being when the word is stretched out (extended) semantically to cover new facts and phenomena of extralinguistic reality (Greasy жирный, маслянистый - переносзначениявабстрактное: скользкийпол, асфальт - негативнаяабстракция: скользкийтип).

Why? Economy of speech resources

How? By virtue of certain similarities between things being observed by the speaker

The nominative-derivative meaning finds no exact equivalent in the classification presented by D. Chrystal, except, probably, fir the term 'connotative meaning' which is used with the reference to the emotional associations which are part of the meaning of a lexical item. (Chrystal, 1985)

Collocationally or colligationally conditioned

This type of meaning is the most important for our research as it includes such words combinations as collocations.

a. Collegationally conditioned meaning is determined by morphosyntactic combinability of words. Some meanings are realized only within a given morphosyntactic pattern (colligation).

Colligation — morphosyntactically conditioned combinability of words as a means of realization of their polysemy.

to tell — рассказать, сказать. In passive constructions means to order/to direct. Ex.: You must do what you’re told; to carry — нести. In passive construction = to accept. Ex.: The amendment(поправка) to the bill was carried.

b. Collocationally conditioned meaning is determined by lexical-phraseological combinability of words.

There are meaning which depend on the word association with other words (collocation).

Collocation — such a combination of words which conditions the realization of a certain meaning.

A herd of cows, a flock of sheep.

Дата добавления: 2018-04-04; просмотров: 1901; Мы поможем в написании вашей работы! |

Мы поможем в написании ваших работ!