Key legal instruments regarding the issue

Study Guide

Irregular migration refers to illegal movement to work in a country without authorization to work, however there is no clear or universally accepted definition of the term. The meaning of this term is pertinent to maritime movements in Southeast Asia. For example, during the 2015 Rohingya Crisis, the kind and amount of aid was administered by each country’s conception of irregular migration.

Irregular migration can be interpreted as an expression of the right to mobility. However, the paradox is that international law supports the right to leave a country but not the right to enter another.

As populations grow, there is an increased likelihood of not fully documenting all refugees and stateless persons. ASEAN has done little to address this issue of documentation. Additionally, those who go through irregular channels are more likely to be at risk of harassment, abuse, and exploitation. There is an openness for the flow of goods and capital, but barriers are put up when it comes to the flow of people. There is an obvious disparity between economic needs and political considerations

Causes, forms and routes of irregular migration:

Causal factors

The imbalance between the number of people seeking residence and the limited permits given by that country. The black market then established networks to deliver persons in return for fees. Geographical proximity, especially in Southeast Asia, further fuels the flow. As a result, there is a tendency to restrict the use of the term "illegal migration" to cases of smuggling of migrants and trafficking in people. People are often exploited in the private economy by individuals or enterprises; are victims of forced sexual exploitation; and/or are victims of forced labour exploitation in economic activities such as agriculture, construction, domestic work, or manufacturing. Others are in state-imposed forms of forced labour. The mixed flows are focussed on irregular populations that include refugees, migrant workers, asylum-seekers, victims of trafficking, smuggled migrants, and unaccompanied minors.

Forms

It includes people who enter a country without the proper authority; who remain in a country in contravention of authority; who move by human trafficking; or those who abuse the asylum system. The line between irregular migrants and asylum seekers and refugees is blurred, as is the distinction between migration control and refugee protection. Asylum seekers and refugees do not lose their protection needs and human rights just because they are part of a mixed flow. What changes is the context in which protection and solutions have to be realised.

|

|

|

Multiple routes

Irregular migration involves irregular channels, including trafficking and smuggling of people. Trafficking of human beings is defined as: the receipt of persons by means of the threat… to achieve the consent of a person having control over another person, for the purpose of exploitation’. The smuggling of migrants is defined as: ‘The procurement… of the illegal entry of a person into a state’.

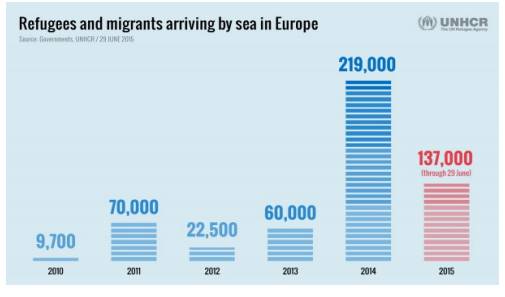

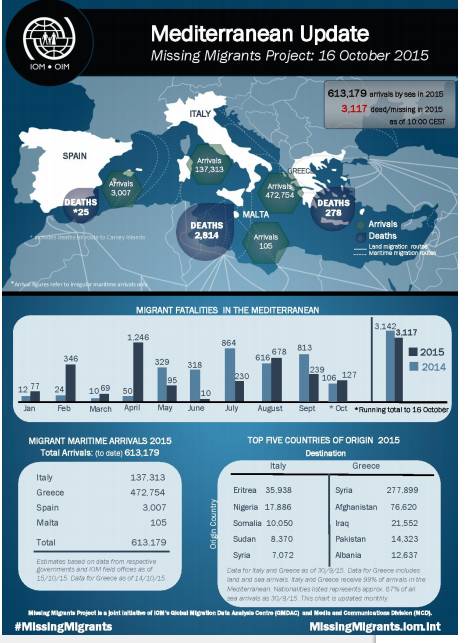

Migrant arrivals and fatalities in the Mediterranean

Tragic losses of lives drowning or succumbing to hunger, thirst, or cold, are reported daily off the coasts of Greece, Italy, Malta and Spain. In reaction to recurrent tragedies, the EU adopted a series of measures seeking to improve the protection of the migrants trying to reach the borders of the EU and to share responsibility among countries involved by increasing cooperation with transit countries. In a Resolution of 29 April 2015, the European Parliament urged the EU and the Member States ‘to do everything possible to prevent further loss of life at sea’1 . On 15 September 2015, a joint hearing of the Committee on Foreign Affairs (AFET), Committee on Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs (LIBE), and Subcommittee on Human Rights (DROI) on ‘Respecting Human Rights in the Context of Migration Flows in the Mediterranean’ took place. A strategic initiative report on the situation in the Mediterranean and the need for a holistic EU approach to migration (2015/2095(INI)) will be presented on 10 December 2015 and adopted later in 2016 in the LIBE Committee. The DROI Subcommittee has requested a study that would feed into the debate and help the Parliament form opinions and make decisions in this respect.

Profile of migrants

According to UNHCR and as Figure 4 below relays, 94 % of the migrants arriving to Europe by sea come from only ten different countries: Syria (59 %), and to a lesser extent from Afghanistan (14 %), Eritrea (6 %), Iraq (4 %), Nigeria (3 %), Pakistan (3 %), Somalia (2 %), Sudan (1 %), Gambia (1 %) and Bangladesh (1 %)

|

|

|

What is quite important, this region is a meeting point of three major religions viz. Christianity, Judaism and Islam, and thus it has always been a hotbed of contradictions. By now these contradictions have become even acuter; furthermore, it is claimed, often justifiably, that the Mediterranean is one of the main victims of the presentday world order, the focal point for global policy-makers, pursing their interest and partaking in the deconstruction of such states as Syria and Libya, thus causing an immense influx of irregular migrants.

Migrants from Syria

Islamic State controlling parts of Syria and Iraq, creating huge instability in the region. Islamic State have spread violence across borders through taped beheadings and executions of ‘infidels’ of all kinds, as well as of Muslims who do not align (whether it is the captured Jordanian fighter pilot or its own followers that smoke cigarettes or are deemed to have offended the Prophet).

This new geopolitical context of violence, insecurity and outright war has huge repercussions for irregular migration and asylum seeking flows. It generates new flows of people in search of basic human security. It also pushes the middle classes of North Africa and the Middle East out of those countries which have failed to democratise and transform, while opening up ‘business opportunities’ for both smuggling and trafficking networks. Finally it provides illusory opportunities to cross into Europe for people fleeing poverty and political instability from countries like Somalia, Eritrea, or Nigeria. The escalation of IS violence and its spreading through guerrillas or infiltrators in Libya, through terrorists in Tunisia, and into other states, further exacerbates these trends.

Key legal instruments regarding the issue.

The profound knowledge of the legal aspects of the issue, viz. the status of migrants, the international standards of their protection is obviously an integral component of awareness in the discussed topic, taken at its state (governmental) level. Moreover, it is in the legal instruments where the universal human values as applied to this particular matter, serving as a kind of jus naturale, are formalized. In the field of determining the status of migrants, the cornerstone role is played by the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, signed and ratified by all EU members. As mentioned above, many of its provisions were anticipated by the ECOSOC’s Study; there are also some derivations from the pre-war conventions governing the same topic11, and especially the Convention of 1933. It was in this document when the non-refoulement principle was enshrined (before that it existed solely within international customary law). This principle, also set out in Article 33 of the 1951 Convention, means the obligation of States not to expel, return or refoule refugees to territories where their life or freedom would be threatened. ‘Refoulement’ may include any measure undertaken by the State which could have an effect of returning an asylumseeker or refugee to the frontiers of territories where his or her life or freedom would be threatened, e.g. rejection at the frontier, interception and indirect refoulement. The principle of non-refoulement is also laid out in the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment; it is vital to note that in this particular document, namely Article 3(1), this guarantee is spread over all types of irregular migrants, not specifically over refugees. But, still, the scope of the 1951. Convention is confined to those already determined as “refugees”, and therefore a proper framework for the legal status of irregular migrants has not been created yet. It is somehow provided in the 1990 International Convention on Protection of the Rights of All Migrants Workers, but its scope is strictly limited. Accordingly the lacuna is distinct here; therefore, it is a fortiori necessary for the state governments to increase their awareness and act in compliance to the aforementioned jus naturale as applied to this particular issue, as well as the general acts concerning human rights, such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Within this context, Articles 5 and 14 of the UDHR are particularly important: the former protects everyone from inhuman or degrading treatment, the latter provides everyone the right to seek and enjoy asylum from persecution in other countries. The former right is also enshrined in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (Article 7). For the reason that this agenda has a lot to do with the EU, mention should be made of its legislation (the so-called ‘communitarian law’) as well, and, first of all, the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union (CFR), where the right to seek asylum is enshrined (Article 18 CFR) and the collective expulsion of aliens is prohibited (Article 19(1) CFR). What’s more, the principle of nonrefoulement is enshrined in this act as well. Within the legal aspect of the problem, it must be clear for the international community that the mere adoption legal instruments filling the lacuna would not guarantee the solution to the problem; even the already existing acts are often hard to implement. The whole body of international law now faces the problem of non-compliance; accordingly of utmost necessity is the raising of legal awareness, as an integral part of global awareness (v.s.), whereas the adoption of new papers must be seen as just a formal stage, surely not as an aim in itself.

|

|

|

Дата добавления: 2018-02-28; просмотров: 285; Мы поможем в написании вашей работы! |

Мы поможем в написании ваших работ!