LITERATURE OF THE GERMANIC TRIBES

The Germanic tribes had a literature, but it was not written down. The stories and poems they made up were repeated and remembered. The Germanic tribes were fond of poetry. Their poems did not remain unchanged. Poets improved them in form and sometimes they changed them to make them more interesting.

At that time there were professional poets too, who went from one place to another or had positions at the courts of kings. They sang songs in which they enlarged and magnified the deeds and events, which the songs were describing. They even sometimes added super natural qualities to a hero.

Most of those early poems were based on historic facts but historic elements were obscured by poetic and mythical additions.

At first all the Germanic tribes were pagans, but then in the 7th century the Anglo-Saxons were converted to Christianity by missionaries who came from the continent. So in the 7th century the Anglo-Saxons became Christians and began composing religious works.

Vocabulary

add [aed] v добавлять addition [s'dijbn] n дополнение adopt [g'dDpt] v принимать Christian ['knstjan] n христианин Christianity Lkristi'asnrti] n христианство compose [ksm'psuz] v сочинять, создавать convert [kan'v3:t] v обращать (в другую веру) establish [is'taeblij] v основывать; создавать

magnify ['msegmfai] v восхвалять

missionary ['гш/пэп] п миссионер

monk [тлпк] п монах

mythical ['гш01кэ1] о фантастический, вымышленный

obscure [sb'skjus] v затемнять

position [pa'zifsn] n должность

quality ['kwoliti] n качество

supenatural [,sju:p3'naetfr3l] а сверхъестественный

14

15

Beowulf

|

|

Beowulf f beiawulf] is the most important poem of the Anglo-Saxon period. Though the Angles brought Beowulf with them to England, it has nothing to do with it. The epic is not even about the Anglo-Saxons, but about the Scandinavians when they lived on the continent in the 3rd or 4th century.

The story of Beowulf was written down in the 10th century by an unknown author, and the manuscripts is now kept in the British Museum. Its social interest lies in the vivid description of the life of that period, of the manners and customs of the people at that time, of the relations among the members of the society and in the portrayal of their towns, ships and feasts.

| Aglo-Saxon warriors |

The scene takes place among the Jutes, who lived on the Scandinavian peninsula at the time. Their neighboms were the Danes. The Jutes and the Danes were good sailors. Their ships sailed round the coast of the peninsula and to far-off lands.

The poem describes the warriors in battle and at peace, during their feasts and amusements. The main hero, Beowulf, is a strong, courageous, unselfish, proud and honest man. He defends his people against the unfriendly forces of nature and becomes the most beloved and kindest king on the earth as the theme of the poem is the straggle of good against evil. Beowulf fights not for his glory, he fights for the benefit of his people.

Although Beowulf was a Jute and his home is Jutland we say that The Song of Beowulf is an English poem. The social conditions it depicted are English. Both the form and the spirit of the poem are English. The poem is a true piece of English literature. The poem is composed with great skill. The author used many vivid

words and descriptive phrases. It is not only the subj ect of the poem that interests us but also its style. Beowulf is one of the early masterpieces of the Anglo-Saxon or Old English language. The poem is famous for its metaphors. For instance, the poet calls the sea "the swan's road", the body — "the bone-house", a warrior — "a heroin-battle", etc.

The Story

|

|

The epic consists of two parts. The first part

tells us how Beowulf freed the Danes from two

monsters. Hrothgar [' hroGga:], King of the

Danes, in his old age had built near the sea a hall

called Heorot. He and his men gathered there

for feasts. One night as they were all sleeping a

frightful monster called Grendel broke into the

hall, killed thirty of the sleeping warriors, and

carried off their bodies to devour them in his lair

under the sea. The horrible half-human crea

ture came night after night. Fear and death

reigned in the great hall. For twelve winters

Grendel's horrible raids continued. At last

the rumour of Grendel and his horrible deeds

crossed over the sea and reached Beowulf

who was a man of immense strength and Aglo-Saxon warrior

courage. When he heard the story, Beowulf decided to fight the monster and free the Danes. With fourteen companions he crossed the sea. This is how his voyage is described in the poem:

The foamy-necked floater fanned by the breeze

Likest a bird glided the waters

Till twenty and four hours hereafter

The twist-stemmed vessel had travelled such distance,

That the sailing-men saw the sloping embankments,

The sea-cliffs gleaming, precipitous mountains.

16

17

The Danes receive Beowulf and his companions with great hospitality, they make a feast in Heorot at which the queen passes the mead cup to the warriors with her own hand. But as night approaches the fear of Grendel is again upon the Danes. They all withdraw after the king has warned Beowulf of the frightful danger of sleeping in the hall. Beowulf stays in the hall with his warriors, saying proudly that since weapons cannot harm the monster, he will wrestle with him bare-handed. Here is the description of Grendel's approach to Heorot:

Forth from the fens, from the misty moorlands, Grendel came gliding — God's wrath be bore — Came under clouds, until he saw clearly, Glittering with gold plates, the mead hall of men. Down fell the door, though fastened with fire bands; Open it sprang at the stroke of his paw. Swollen with rage burst in the bale-bringer; Flamed in his eyes a fierce light, likest fire.

Breaking into the hall, Grendel seizes one of the sleepers and devours him. Then he approaches Beowulf and stretches out a claw, only to find it clutched in a grip of steel. A sudden terror strikes the monster's heart. He roars, struggles, tries to free his arm; but Beowulf leaps to his feet and grapples his enemy barehanded. After a desperate struggle Beowulf manages to tear off the monster's arm; Grendel escapes shrieking across the moor, and plunges into the sea to die.

Beowulf hangs the huge arm with its terrible claws over the king's seat; the Danes rejoice in Beowulf's victory. When night falls, a great feast is spread in Heorot. Beowulf receives rich presents, everybody is happy. The Danes once more go to sleep in the great hall. At midnight comes another monster, mother of Grendel, who wants to revenge her son. She seizes the king's best friend and councillor and rushes away with him over the fens. The old king is broken-hearted, but Beowulf tries to console him:

Sorrow not, wise man. It is better for each

That his friend he avenge than that he mourn much.

Each of us shall the end await

Of worldly life: let he who may gain

Honour ere1 death.

Then Beowulf prepares for a new fight. He plunges into the horrible place, while his companions wait for him on the shore. After a terrible fight at the bottom of the sea in the cave where the monsters live, Beowulf kills the she-monster with a magic sword which he finds in the cave. The hero returns to Heorot, where the Danes are already mourning for him, thinking him dead. Triumphantly Beowulf returns to his native land.

In the last part of the poem there is another great fight. Beowulf is now an old man; he has reigned for fifty years, beloved by all his people. He has overcome every enemy but one, a fire dragon keeping watch over an enormous treasure hidden among the mountains. Again Beowulf goes to fight for his people. But he is old and his end is near. In a fierce battle the dragon is killed, but the fire has entered Beowulf's lungs.

He sends Wiglaf, the only of his warriors who had the courage to stand by him in his last fight, to the dragon's cave for the treasures. Beowulf dies, leaving the treasures to the people.

Vocabulary

| companion [кэт'рэегуэп] п товарищ compose [кэт'рэш] v сочинять console [ksn'sgul] v утешать contents ['kontgnts] n содержание councillor ['kaunsita] n советник courageous [ka'reid^as] а смелый, отважный creature ['kritjb] n создание; живое существо deed [di:d] n поступок; подвиг |

avenge [a'vencfo] v мстить

bale [beil] n несчастье; горе

band [bsnd] n полоса

bare-handed ['beg'haendid] а голыми

руками (без оружия) bear [Ьеэ] v (bore; borne) нести benefit ['benifit] n польза, благо breeze [bri:z] n (легкий) ветерок claw [klo:] n лапа с когтями; коготь clutch [kktj] v зажать

ere [еэ] — поэтич. перед

18

19

depict [di 'pikt] v изображать, описывать

descriptive [dis 'knptivj о описательный; наглядный

desperate ['despant] а отчаянный; ужасный

devour [di'vaua] v пожирать

dragon ['draegan] n дракон

embankment [im'bcerjkmsnt] n насыпь

enormous [I'noimas] о громадный, огромный

epic ['epik] n эпическая поэма

evil [i:vl] n зло

fan [fsen] v поэт, обвевать, освежать (о ветерке)

fasten ['fa:sn] v скреплять; укреплять

fear [йэ] л страх

feast [first] n пир; празднество

fen [fen] л болото, топь

floater f'flauta] n плот, паром

foamy ['fbumi] о покрытый пеной

frightful ['fraitful] о страшный, ужасный

gleam [gli:m] v светиться; мерцать

glide [glaid] v двигаться крадучись

glitter ['gilts] v блестеть, сверкать

grapple ['graepl] v схватиться, бороться

grip [grip] n сжатие

harm [ha:m] v вредить, причинять вред

hospitality Lhnspi'taeliti] n гостеприимство

immense [i 'mens] а огромный, громадный

lair [1еэ] п логовище; нора

leap [li:p] v (leapt, leaped) прыгнуть, вскочить

manuscript ['maenjusknpt] n рукопись

masterpiece ['ma:stapi:s] n шедевр

mead [mi:d] n мёд (напиток)

metaphor ['metafa] n метафора

misty ['misti] а туманный

monster ['rrmnsta] n чудовище

moorland ['mualand] местность, поросшая вереском

mourn [mo:n] v оплакивать; скорбеть

overcome [^эшэ'клт] v (overcame; overcome) побороть, победить

paw [po:] n nana

peninsula [pi'ninsjula] n полуостров

plunge ['pUnay v нырять; бросаться

portrayal [po:'treial] n описание; изображение

precipitous [pn' srpitas] n крутой; отвесный

rage [reidj;] n ярость, гнев

raid [reid] n набег

rejoice [n'djois] v радоваться

roar [ro:] v реветь, рычать

rumour ['ш:тэ] п слух, молва

scene [si:n] n место действия

shriek [fri:k] v пронзительно кричать, орать

sloping ['slaupirj] а покатый

spirit ['spirit] n дух

stroke [strauk] n удар

subject ['sAbdpkt] n тема

swollen ['swaulan] а опухший; раздутый

sword [so:d] n меч

theme [9i:m] л тема

twist [twist] v крутить; виться twist-stemmed vessel судно с витым носом

vivid ['vivid] а яркий

warn [wo:n] v предупреждать

wrath [ro:9] n гнев, ярость

wrestle ['rest] v бороться

Questions and Tasks

1. When was poem Beowulf compiled?

2. What is the social interest of the poem?

3. What time does the poem tell us of?

4. Where is the scene of the poem set?

5. What does the poem tell us about the Jutes and the Danes?

6. What kind of man was the young knight of the Jutes Beowulf?

7. How is the poem composed?

8. What interests us besides the subject of the poem?

9. What is the poem famous for?

10. Retell the contents of Beowulf.

20

Anglo-Saxon Literature

(the 7th-11th centuries)

The culture of the early Britons changed greatly under the influence of Christianity. Christianity penetrated into the British Isles in the 3rd century. It was made the Roman national faith in the year 306 when Constantine the Great became emperor over the whole of the Roman Empire. The religion was called the Catholic Church (the word "Church" means "religion", "catholic" means "universal"). The Greek and Latin languages became the languages of the Church all over Europe.

At the end of the 4th century, after the fall of the Roman Empire, Britain was conquered by Germanic tribes. They were pagans. They persecuted the British Christians and put many of them to death or drove them away to Wales and Ireland.

At the end of the 6th century monks came from Rome to Britain again with the purpose to convert the Anglo-Saxons to Christianity. You know that in the 7th century the Anglo-Saxons were converted to Christianity.

The part of England where the monks landed was Kent and the first church they built was in the town of Canterbury. Up to this day it is the English religious centre. Now that Roman civilization

poured into the country again, a second set of Latin words was introduced into the language of the Anglo-Saxons, because the religious books that the Roman monks had brought to England were all written in Latin and Greek. The monasteries where the art of reading and writing was practised became the centres of almost all the learning and education in the country. No wonder many poets and writers imitated those Latin books about the early Christians, and they also made up many stories of their own aboiit saints. Though the poets were English, they had to write in Latin. Notwithstanding this custom, a poet appeared in the 7th century by the name of Caedmon Г kaedman] who wrote in Anglo-Saxon. He was a shepherd, who started singing verses and became a poet. Later monks took him to a monastery where he made up religious poetry. He wrote a poem — the Paraphrase ['pserafreiz]. It tells part of a Bible-story.

Another writer of this time was Bede [bi: d]. He described the country and the people of his time in his work The History of the English Church. His work was a fusion of historical truth and fantastic stories. It was the first history of England and Bede is regarded as "the father of English history".

|

|

Another outstanding figure in En glish history and literature was Alfred the Great (849-901), the king of Wessex. Though he was a soldier he fought no wars except those in order to defend his country. He built a fleet of ships to beat the Danes who had again come to invade Wessex. He also made up a code of law. He tried to develop the culture of his people. He founded the first English public school for young men. He translated the Church-history of Bede from Latin into a language the people could understand, and a portion of the Bible as well. To him the English owe the famous Anglo- The Venerable writing the life of

„ _,, . , , . , , St Cuthbert, the monk who spread

ЬахОП LhrOIUCle Which may be Christianity in the north of Britain

22

23

| called the first history of England, the first prose in English literature. It was continued for 250 years after the death of Alfred, till the reign of Henry II in 1154. |

| Questions and Tasks • 1. When did Christianity penetrate the British Isles? 2. When was it made the Roman national faith? 3. What was the religion called? 4. What languages became the languages of the Church all over Europe? 5. Why did monks come from Rome to Britain at the end of the 6th century? 6. When were the Anglo-Saxons converted to Christianity? 7. Where did the monks land? 8. Where was the first church built? 9. Why did the monasteries become the centres of all the learning and education?

10. What language did the English poets have to write? 11. What representatives of Anglo-Saxon literature can you name? 12. What poem did Caedmon write? 13. Say about Bede and his work. 14. Speak about the contribution of king Alfred to the development of English literature and culture. |

Vocabulary

Catholic ['каевэИк] a католический Christian ['knstjsn] n христианин Christianity [.kristi'asniti] n христианство code [koud] n свод законов contribution [,kcntrf bju:Jbn] n вклад convert [kan'v3:t] v обращать (в другую веру) emperor ['етрэгэ] п император empire ['empara] n империя faith [feiG] л вера fusion ['fjirjsn] п слияние imitate ['imiteit] v подражать, имитировать influence ['mfluans] n влияние introduce [,mtra'dju:s] v вводить monastery ['rrronsstsri] n монастырь

notwithstanding [,rrotwi9'staendm] prep

несмотря на owe [эи] v быть обязанным penetrate ['penitreit] v проникать persecute ['p3:sikju:t] v преследовать,

подвергать гонениям portion ['рэ:/эп] п часть pour [рэ:] v вливать regard [n'ga:d] v рассматривать saint [semt] n святой set [set] n ряд shepherd ['Jepad] n пастух universal [Ju:m'v3:sal] а всеобщий venerable ['vensrabl] о преподобный

(о святом)

THE DANISH CONQUEST AND ITS INFLUENCE ON THE LANGUAGE OF THE ANGLO-SAXONS

When King Alfred died, fighting with the Danes soon began again. They occupied the north and east of England (Scotland and Ireland) and also sailed over the Channel and fought in France.

The land they conquered in the North of France was called Normandy and the people who lived there the Northmen. In the hundred years that were to follow they began to be called Normans.

The Danes who had occupied the North and East of England spoke a language only slightly different from the Anglo-Saxon dialects. The roots of the words were the same while the endings were different. Soon these languages merged with one another as they were spoken by all classes of society. The language of the Anglo-Saxons took many new words from Danish, particularly those regarding state affairs and shipbuilding. Such words as law, ship, fellow, husband, sky, ill are of Scandinavian origin. The Danes were in many ways more civilized than the English. The Danes were accustomed to chairs and benches while the English still sat on the floor. The Danes brought the game of chess to England which originally had come to them from the East.

Vocabulary

accustom [a'kAStam] v приучать Northman ['по:8тэп] п норманн

affair [эТеэ] п дело origin ['ппфп] п происхождение

civilized ['smlaizd] а цивилизованный originally [э'гк%пэ11] adv первоначально

comment ['tomant] v комментировать regarding [n'ga:dm] prep относительно,

conquest ['kurjkwast] л завоевание что касается

dialect ['daislekt] л диалект root [ru:t] n корень

merge [тз:сй v сливаться, соединяться slightly ['slaitli] adv слегка

Normandy ['rmnandi] n Нормандия

24

25

"

Questions and Tasks

1. When did fighting with the Danes begin again?

2. What part of the country did they occupy?

3. What name was given to the land in the north of France?

4. What language did the Northmen speak?

5. What do you know about the language the Danes spoke?

6. Comment on the development of the English language influenced by the Danish invasion.

|

|

The Norman Period

(the 12th-13th centuries) THE NORMAN CONQUEST

The Northmen or the Vikings who had settled in Northwestern France were called Normans. They had adopted the French civilization and language. They were good soldiers, administrators and lawyers.

In 1066 at the battle of Hastings [ 'heistrnz] the Norman Duke William defeated the Saxon King Harold. Again a new invasion took place. Within five years William the Conqueror was complete master of the whole of England. He divided the land of the conquered people among his lords. With the Norman conquest the feudal system was established in England. The English peasants were made to work for the Norman barons, they became their serfs and were cruelly oppressed.

William the Conqueror could not speak a word of English. He and his barons spoke Norman-French, not pure French, because the Normans were simply the same Danes with a French polish. The English language was neglected by the conquerors.

Norman-French became the official language of the state and

27

remained as such up to the middle of the 14th century. It was the language of the ruling class, of the court and the law, it was spoken by the Norman nobility.

But the common people of the native population kept speaking their mother tongue, Anglo-Saxon. While at the monasteries, at the centres of learning, the clergy used Latin for services and the literary activities.

In the Norman times three languages were spoken in the country. Until the 12th century it was mostly monks who were interested in books and learning. With the development of sciences, such as medicine and law, "Universities" appeared in Europe. Paris became the centre of higher education for English students.

In 1168 a group of professors from Paris founded the first university at Oxford. In 1209 the second university was formed at Cambridge. The students were taught Latin, theology, medicine, grammar, rhetoric, logic, arithmetic, geometry, astronomy and music.

By and by the elements of French and Latin penetrated into Anglo-Saxon. They belonged to all spheres of life-words denoting relations, religious terms, words connected with government and military terms. War, pbace, guard, council, tower, wage, comfort, beef, tailor — all these words are of French origin. Sometimes the French words replaced the corresponding English words, sometimes they remained side by side forming synonyms. A well-known example of such differentiation is presented by the names of animals, which were of Anglo-Saxon origin, and the name of the meat of these animals, which was French, such as ox-beef, calf-veal, sheep-mutton etc. Enriched by French and Latin borrowings, their language still remained basically Anglo-Saxon.

Finally it became the national language (we now call it Middle English). The formation of the national language was completed in the 14th century.

In 1349 English began to be studied in schools. In 1366 it was adopted in the courts of Law.

Vocabulary

| nobility [nau'bihti] л знать oppress [a'pres] v угнетать peasant ['pezsnt] л крестьянин polish [poilj] л тонкость, изысканность pure [pjua] а правильный replace [n'pleis] v заменять rhetoric ['retsnk] n риторика serf [s3:f] л крепостной sphere fsfis] л сфера, круг state1 [steit] л состояние state2 [steit] n государство term [t3:m] л термин theology [9i'rjl3cfei] n богословие tonque [Un] л язык wage [weictj] n заработная плата |

adopt [s'dnpt] v принимать basically ['beisiksli] adv в основном borrowing ['bDrsuin] л заимствование briefly [bri:fli] adv кратко clergy ['kl3:d^i] n духовенство complete [ksm'plil] о полный; v заканчивать corresponding [^kDns'prmdin] о соответствующий council ['kaunsil] л совет court [ko:t] л суд differentiation [^difsrenfi'eijsn] n раз

личение establish [is'taeblif] v основать neglect [m'glekt] v пренебрегать

Questions and Tasks

1. What was the name of the Northmen?

2. When did the battle of Hastings take place?

3. Who conquered England?

4. How many years was William the Conqueror complete master of the whole

of England?

5. Describe the conditions of peasants after the Norman conquest.

6. What language became the official language of the state?

7. Who spoke Anglo-Saxon?

8. What language did the clergy use?

9. How many languages were spoken in the Norman times?

10. Who was interested in books and learning until the 12th century?

11. What city became the centre of higher education for English students?

12. Where were the first and the second universities formed?

13. What subjects were the students taught there?

14. Comment on the state of the English language after the Norman Conquest.

15. When was the formation of the national language completed?

16. When did English begin to be studied in schools?

17. When was it adopted in the courts of Law?

18. Relate briefly the story of the Normans and the Norman Conquest.

28

29

LITERATURE IN THE NORMAN TIMES

LITERATURE IN THE NORMAN TIMES

The Normans brought to England romances — love stories and lyrical poems about their brave knights and their ladies.

The first English romances were translations from French. But later on in the 12th century, there appeared romances of Arthur, a legendary king of Britain. In the 15th century Thomas Malory collected and published them under the title Sir Thomas Malory's Book of King Arthur and of his Noble Knights of the Round Table. The knights gathered in King Arthur's city of Camelot f kaemiltrt]. Their meetings were held at a round table, hence the title of the book. All the knights were brave and gallant in their struggle against robbers, bad kings and monsters. King Arthur was the wisest and most honest of them all.

The townsfolk expressed their thoughts in fabliaus [ 'fasbliauz] (funny stories about townsfolk) and fables. Fables were short stories with animals for characters and contained a moral.

Anglo-Saxon was spoken by the common people from the 5th till the 14th century. The songs and ballads about harvest, mowing, spinning and weaving were created by the country-folk, and were learnt by heart, recited and sung accompanied by musical instruments and dancing."

4. Who collected and published the romances?

5. Under what title did Thomas Malory collect the books?

6. What was the book about?

7. Where did the townsfolk express their thoughts?

8. What was created by the country-folk?

9. Say how the Norman Conquest affected English literature.

Vocabulary

Vocabulary

accompany [э'клтрэга] ^сопровождать legendary ['leapndgn] а легендарный

contain [кэп Чет] v содержать mowing ['тэшп] п косьба

fable f'feibl] n басня recite [rfsait] v декламировать

fabliau [fae'blisu] n фабльо romance [re'maens] n роман

gallant ['gsebnt] а храбрый spinning ['spmm] n прядение

hence [hens] adv отсюда weaving ['wi:virj] n тканье

knight [nait] л рыцарь wise [waiz] а мудрый

Questions and Tasks

1. What stories did the Normans bring to England?

2. What were the first English romances?

3. What romances appeared in the 12th century?

30

*

English Literature in the 14th Century

PRE-RENAISSANCE IN ENGLAND

The Norman kings made London their residence. The London dialect was the central dialect, and it was understood throughout the country. It was the London dialect from which the national language developed.

In the 14th century the English bourgeoisie traded with Flanders (now Belgium). The English sold wool to Flanders and the latter produced the finest cloth. England wanted to become the centre of the world market. Flemish weavers were invited to England to teach the English their trade. But feudalism was a serious obstacle to the development of the country. In the first half of the 14th century France threatened the free towns of Flanders, wishing to seize them. England was afraid of losing its wool market.

A collision between France and England was inevitable. King Edward III made war with France in 1337. This war is now called the Hundred Years' War because it lasted over a hundred years. At first England was successful in the war. The English fleet defeated the French fleet in the Channel. Then the English also won battles on

land. B\it the ruin of France and the famine brought about a terrible disease called the "pestilence". It was brought over to England from France. The English soldiers called it the "Black Death". By the year 1348 one-third of England's population had perished. The peasants who had survived were forced to till the land of their lords.

As years went on, the French united against their enemy. As the king needed money for the war, Parliament voted for extra taxes. The increasing feudal oppression, cruel laws and the growth of taxes aroused people's indignation and revolts broke out all over the country. In 1381 there was a great uprising with Wat Tyler at the head. The rebels set fire to the houses, burnt valuable things, killed the king's judges and officials. They demanded the abolition of serfdom and taxes, higher wages and guarantees against feudal oppression. But the rebellion was suppressed, and Wat Tyler was murdered.

Nothing made the people so angry as the rich foreign bishops of the Catholic Church who did not think about the sufferings of the people. The protest against the Catholic Church and the growth of national feeling during the first years of the Great War found an echo in literature. There appeared poor priests who wandered from one village to another and talked to the people. They protested against the rich bishops and also against all churchmen who were ignorant men and did not want to teach the people anything.

Such poor priests were the poet William Langland and John4 Wycliffe. They urged to fight for their rights. But the greatest writer of the 14th century was Geoffrey Chaucer, who was the writer of the new class, the bourgeoisie. He was the first to clear the way for realism.

Vocabulary

| ignorant ['ignsrent] а невежественный indignation [^mdig'neifan] n возмущение, негодование inevitable [m'evitabl] а неизбежный latter ['tets] а последний obstacle ['obstakl] л препятствие official [s'ftjbl] n чиновник; служащий oppression [э'рге/эп] л угнетение; гнет outcome ['autksm] л последствие |

abolition Laebs'lifgn] л отмена bishop ['bijbp] л епископ collision [кэ'11зэп] л столкновение echo ['екэи] л отражение famine ['fsemm] л голод Flanders ['flaindaz] л Фландрия Flemish ['flemij] а фламандский force [fo:s] v заставлять guarantee Lgasran'ti:] v гарантировать

32

33

| perish ['penfl v погибать pestilence ['pestibns] n чума rebellion [n'beljsn] n восстание revolt [ri'vault] n восстание serfdom ['s3:fdsm] n крепостное право suppress [sa'pres] v подавлять survive [sg'vaiv] v выжить, уцелеть |

tax [tasks] n налог threaten ['Gretn] v угрожать throughout [9ru:'aut] adv повсюду till [til] v обрабатывать (землю), пахать urge [з:с&] v побуждать, заставлять wander ['wands] v бродить weaver ['wirval n ткач

Questions and Tasks

1. Describe the political situation of England in the 14th century.

2. How did people react to growing feudal oppression?

3. Talk about Wat Tyler's Rebellion and its outcome.

4. What was the result of the protest against the Catholic Church?

5. What did poor priests protest against?

6. What do you know about the poets William Langland and John Wycliffe?

7. Who was the greatest writer of the 14th century?

Geoffrey Chaucer

(1340-1400)

| Geoffrey Chaucer |

The most vivid description of the 14th century England was given by Geoffrey Chaucer [ 'd3efn 'tfo:ss]. He was the first truly great writer in English literature and is called the "father of English poetry". Chaucer was born in London, into the family of a wine merchant. His father had connections with the court and hoped for a courtier's career for his son. At seventeen Geoffrey became page to a lady at the court of Edward III. At twenty, Chaucer was in France, serving as a squire. During 1373 and the next few years Chaucer travelled much and lived a busy life. He went to France, made three journeys to Italy. Italian literature opened to Chaucer a new world of art. Chaucer's earliest poems were written in imitation of the French romances.

The most vivid description of the 14th century England was given by Geoffrey Chaucer [ 'd3efn 'tfo:ss]. He was the first truly great writer in English literature and is called the "father of English poetry". Chaucer was born in London, into the family of a wine merchant. His father had connections with the court and hoped for a courtier's career for his son. At seventeen Geoffrey became page to a lady at the court of Edward III. At twenty, Chaucer was in France, serving as a squire. During 1373 and the next few years Chaucer travelled much and lived a busy life. He went to France, made three journeys to Italy. Italian literature opened to Chaucer a new world of art. Chaucer's earliest poems were written in imitation of the French romances.

The second period of Chaucer's literary work was that of the Italian influence. To this period belong the following poems: The House of Fame, The Parliament of Fowls, a poem satirizing Parliament, The Legend of Good Women and others.

When Chaucer came back to England, he received the post of Controller of the Customs in the port of London. Chaucer held this position for ten years. He devoted his free time to hard study and writing. Later Chaucer was appointed "Knight for the Shire of Kent", which meant that he sat in Parliament as a representative for Kent.

He often had to go on business to Kent and there he observed the pilgrimages to Canterbury.

The third period of Chaucer's creative work begins in the year 1384, when he started writing his masterpiece, The Canterbury Tales.

Chaucer died in 1400 and was buried in Westminster Abbey. Chaucer was the last English writer of the Middle Ages and the first of the Renaissance.

Vocabulary

| post [psust] n поет, должность satirize ['saetaraiz] v высмеивать shire [fara] n графство source [so:s] n источник vivid ['vivid] о яркий |

court [ko:t] n двор короля courtier ['кэ:ф] п придворный esquire [is'kwaia] n оруженосец pilgrimage ['pilgnmKfe] n паломни чество

Questions and Tasks

1. Give the main facts of Chaucer's life.

2. What were the sources of Chaucer's creative work?

3. Speak about the three periods of Chaucer's creative work.

4. What is his masterpiece?

5. When did Chaucer die?

6. Where was he buried?

34

35

The Canterbury Tales

This is the greatest work of Chaucer in which his realism, irony and freedom of views reached such a high level that it had no equal in all the English literature up to the 16th century. That's why Chaucer was called "the founder of realism". It is for the Canterbury Tales that Chaucer's name is best remembered. The book is an unfinished collection of stories in verse told by the pilgrims on their journey to Canterbury. Each pilgrim was to tell four stories. Chaucer managed to write only twenty-four instead of the proposed one hundred and twenty-four stories.

All his characters are typical representatives of their classes. When assembled, they form one people, the English people. Chaucer kept the whole poem alive and full of humour not only by the tales themselves but also by the talk, comments and the opinions of the pilgrims.

The prologue is the most interesting part of the work. It acquaints the reader with medieval society. The pilgrims are persons of different social ranks and occupations. Chaucer has portrayed them with great skill at once as types and as individuals true to their own age. There is a knight, a yeoman (a man who owned land; a farmer), a nun, a monk, a priest, a"merchant, a clerk, a sailor, Chaucer himself and others, thirty-one pilgrims in all. The knight is brave, simple and modest. He is Chaucer's ideal of a soldier. The nun weeps seeing a mouse caught in a trap but turns her head from a beggar in his "ugly rags". The fat monk prefers hunting and good dinners to prayers. The merchant's wife is merry and strong. She has red cheeks and red stockings on her fat legs. The clerk is a poor philosopher who spends all his money on books.

Each of the travellers tells a different kind of story showing his own views and character. Some are comical, gay, witty or romantic, others are serious and even tragic.

In Chaucer's age the English language was still divided by dialects. Chaucer wrote in the London dialect, the most popular one at that time. With his poetry the London dialect became the English literary language. Chaucer does not teach his readers what is good or bad by moralizing; he was not a preacher. He merely paid

|

|

joi

*mi

Pilgrims on their journey to Canterbury

attention to the people around him; he drew his characters "according to profession and degree", so they instantly became typical of their class.

Vocabulary

| merely ['miali] adv только, просто moralize ['rrrorelaiz] v поучать nun [плп] п монахиня pilgrim ['pilgrim] n паломник prayer ['preis] n молитва preacher ['pritfa] л проповедник prologue fprsulog] n пролог rank [rserjk] n звание; ранг trap [trsep] n капкан weep [wi:p] v (wept) плакать yeoman Пэитэп] п иомен, фермер |

appoint [a'pomt] v назначать assemble [o'sembl] v собираться career [кэ'пэ] п карьера comment [ 'knmsnt] n комментарий,

толкование degree [di'gri:] n положение, ранг equal ['i:kwal] а равный framework ['freimw3:k] n структура instantly ['mstanth] adv немедленно level ['levl] n уровень medieval [^medi'i^sl] а средневековый

36

37

Questions and Tasks

1. Thanks to what work is Chaucer's name best remembered?

2. Describe the framework of the Canterbury Tales.

3. Speak on the characters'of the Canterbury Tales as typical representatives of their time.

4. Speak on the subject and form of the tales.

5. Comment on the state of the English language at the beginning of the 14th century and Chaucer's contribution to the development of the English language.

6. Speak on Chaucer's place in English literature.

English Literature in the 15th Century

i THE WARS OF THE ROSES

The death of Chaucer was a great blow to English poetry. It took two centuries to produce a poet equal to him. The Hundred Years' War ended, but another misfortune befell the country: a feudal war broke out between the descendants of Edward III in the 15th century.

When the English were completely driven out of France by 1453, the Yorkists took up arms against the Lancastrians, and in 1455 the Wars of the Roses began.

It was a feudal war between the big barons of the House of Lancaster, wishing to continue the war with France and to seize the lands of other people thus increasing their land possessions and the lesser barons and merchants of the House of York, who wished to give up fighting in France as it was too expensive for them (The Yorkists had a white rose in their coat of arms, hence the name of the war).

When the Wars of the Roses ended in 1485 Henry VII was proclaimed King of England. The reign of the Tudors was the beginning of an absolute monarchy in England, and at the same time it helped to do away with feudal fighting once and for all.

39

Vocabulary

befall [bf foil] vjbefell; befallen) случаться lesser ['lesa] а мелкий

coat of arms ['ksutav'aimz] n герб proclaim [pra'kleim] vобъявлять; про-

descendant [di'sendsnt] n потомок возглашать

Lancastrian [laen'kEestnan] n сторон- Yorkist ['p:kist] n сторонник Йоркской

ник Ланкастерской династии династии

Questions and Tasks

1. What misfortune befell England in the 15th century?

2. When did the Wars of the Roses begin?

3. Talk about the reasons for the war.

4. When did the war end?

5. Who was proclaimed King of England?

6. What was the reign of the Tudors for England?

Folk-Songs and Ballads

Though there was hardly any written literature in England in the 15th century, folk poetry flourished in England and Scotland. Folk-songs were heard everywhere. Songs were made up for every occasion. There were harvest songs, mowing songs, spinning and weaving songs, etc.

The best of folk poetry were the ballads. A ballad is a short narrative in verse with the refrain following each stanza. The refrain was always one and the same. Ballads were often accompanied by musical instruments and dancing. They became the most popular form of amusement. Some ballads could be performed by several people because they consisted of dialogues.

There were various kinds of ballads: historical, legendary, fantastical, lyrical and humorous. The ballads passed from generation to generation through the centuries — that's why there are several versions of the same ballads. So about 305 ballads have more than a thousand versions.

The most popular ballads were those about Robin Hood.

The art of printing did not stop the development of folk-songs and ballads. They continued to appear till the 18th century when

40

they were collected and printed. The common people of England expressed their feelings in popular ballads.

Vocabulary

flourish ['АлпГ] v процветать refrain [n'frem] n припев

generation [^djem'reijbn] n поколение stanza ['staenza] n строфа

narrative ['naeretrv] n повествование version ['v3:Jsn] п вариант

occasion [э'кегзэп] п случай

Questions and Tasks

1. What poetry flourished in England in the 15th century?

2. What kind of songs were there?

3. What was the best of folk poetry?

4. What is a ballad?

5. Why could some ballads be performed by several people?

6. What kinds of ballads were there?

7. Explain why there are several versions of the same ballads.

8. What were the most popular ballads?

The Robin Hood Ballads

England's favourite hero, Robin Hood, is a partly legendary, partly historical character. The old ballads about the famous outlaw say that he lived in about the second half of the 12th century, in the times of King Henry II and his son Richard the Lion-Heart. Society in those days was mainly divided into lords and peasants. Since the battle of Hastings (1066) the Saxons had been oppressed by the Normans. In those days many of the big castles belonged to robber-barons who ill-treated the people, stole children, took away the cattle. If the country-folk resisted, they were either killed by the barons or driven away, and their homes were destroyed. They had no choice but to go out in bands and hide in the woods; then they were declared "outlaws" (outside the protection of the law).

The forest abounded in game of all kinds. The Saxons were good hunters and skilled archers. But in the reign of Henry II the

41

numerous herds of deer were proclaimed "the king's deer" and the forests "the king's forests". Hunting was prohibited. A poor man was cruelly punished for killing one of those royal animals. This was the England of Robin Hood about whom there are some fifty or more ballads.

Robin Hood

Robin Hood is a brave outlaw. In Sherwood Forest near Nottingham there was a large band of outlaws led by Robin Hood. He came from a family of Saxon land owners, whose land had been seized by a Norman baron. Robin Hood took with him all his family and went to the forest. The ballads of Robin Hood tell us of his

adventures in the forest as an outlaw. Many Saxons joined him there. They were called "the merry men of Robin Hood".

Robin Hood was strong, brave and clever. He was much cleverer, wittier and nobler than any nobleman. He was the first in all competitions. Robin Hood was portrayed as a tireless enemy of the Norman oppressors, a favourite of the country folk, a real champion of the poor. He was generous and tender-hearted and he was always ready to respond to anybody's call for help. His worst enemies were the Sheriff of Nottingham, the bishop and greedy monks. He always escaped any trouble and took revenge on his enemies. Robin Hood was a man of a merry joke and kind heart.

The ballads tell us of Robin Hood's friends — of Little John who was ironically called "little" for being very tall; of thejolly fat Friar Tuck who skilfully used his stick in the battle. Their hatred for the cruel oppressors united them and they led a merry and free life in Sherwood Forest.

The ballads of Robin Hood gained great popularity in the second half of the 14th century when the peasants struggled against their masters and oppressors. The ballads played an important role in the development of English poetry up to the 20th century. They became so popular that the names of their authors were forgotten.

Vocabulary

| mainly ['memli] adv главным образом outlaw ['autlo:] n изгнанник proclaim [pre'kleim] v объявлять; провозглашать prohibit [prs'hibit] v запрещать resist [n'zist] v сопротивляться respond [ns'ptmd] v отозваться revenge [rf vend^] n месть take revenge отомстить tender-hearted ['tendg'haitid] а добрый; отзывчивый |

abound [a'baund] v изобиловать archer ['aitja] n стрелок из лука avoid [s'void] v избегать band [baend] n отряд, группа crude [kra:d] а грубый gain [gem] v добиться game [geim] n дичь generous ['gemras] а великодушный herd [h.3:d] n стадо ill-treat ['il'tiit] v дурно, жестоко обращаться jolly ['<%d!i] а веселый

42

43

|

|

Questions and Tasks

1. What did the old ballads say about the time Robin Hood lived?

2. Describe the conditions of the Saxons after the Norman Conquest.

3. What family did Robin Hood come from?

4. What kind of man was he?

5. Who were his worst enemies?

6. Who were his friends?

7. How was Robin Hood portrayed in the ballads?

8. When did the ballads of Robin Hood gain great popularity?

! English Literature

I in the 16th Century

Henry VII was proclaimed King of England after the Wars of the Roses ended. Most of the great earls had killed one another in these wars and Henry VII was able to seize their lands without difficulty and give them to those who had helped him to fight for the Crown.

Thousands of small landowners appeared in England. They called themselves "squires". The squires let part of their estates to farmers who paid rent for the use of this land. The farmers, in their turn, hired labourers to till the soil and tend the sheep. The peasants in the villages had land and pastures in common.

By the reign of Henry VIII (son of Henry VII) trade had expanded. Trading companies sprang up and ships were built fitted to cross the ocean.

The English bourgeoisie strove for independence from other countries. The independence of a country is associated with the struggle for freedom. The Catholic Church was the chief obstacle and England rebelled against the Pope of Rome. Henry VIII made himself head of the English Church and took away monastic wealth (the lands and money that belonged to the monasteries), giving it to those of the bourgeoisie who sat in Parliament.

45

|

Questions and Tasks 1. Who was proclaimed King of England after the Wars of the Roses? 2. Describe the situation in England after the war. 3. What did the English bourgeoisie strive for? 4. What was the chief obstacle? 5. Did the Church in England become part of the state? 6. What was it called? 7. What country was England's rival? 8. When did England inflict a defeat on the Spanish Invincible Armada? 9. Speak about the situation in England after the war with Spain. |

| THE RENAISSANCE |

| The word "renaissance" [гэ 'neisans] means "rebirth" in French and was used to denote a phase in the cultural development of Europe between the 14th and 17th centuries. The Middle Ages were followed by a more progressive period due to numerous events. The bourgeoisie appeared as a new class. Italy was the first bourgeois country in Europe in the 14th century. |

|

|

The Pope resisted England's struggle for independence, but the Church in England became part of the state. It was called the Anglican Church.

| Elizabeth I |

All the progressive elements now gathered around Queen Elizabeth (1558-1603). Even Parliament helped to establish an absolute monarchy in order to concentrate all its forces in defence of the country's economic interests against Spain, as Spain and England were rivals. Soon war between Spain and England broke out. Though the Spanish fleet was called the "Invincible Armada" ("invincible" means "unconquerable"), their ships were not built for sea battles, while the English vessels were capable of fighting under sail. The Armada was thoroughly beaten and dreadful storm overtook tke fleet and destroyed almost all ships.

But in England all was joy and happiness. This was in 1588. Victory over the most dangerous political rival consolidated Great Britain's might on the seas and in world trade. Numerous English ships under admirals Drake, Hawkings and others sailed the seas, visited America and other countries, bringing from them great fortunes that enriched and strengthened the Crown.

At the same time 16th century witnessed great contradictions between the wealth of the ruling class and the poverty of the people.

New social and economic conditions brought about great changes in the development of science and art. Together with the development of bourgeois relationship and formation of the English national state this period is marked by a flourishing of national culture known in history as the Renaissance.

Vocabulary

associate [s'sgufieit] v ассоциировать

chief [tjl:f] о главный

common ['кглпэп] п общинная земля

consolidate [ksn'sulideit] v укреплять

contradiction [^knntra'dikfsn] n противоречие .

crown [kraun] n монарх

earl [з:1] п граф

estate [is'teit] n поместье

expand [iks'psend] v развиваться, расширяться

fit [fit] v соответствовать

hire [haia] v нанимать

independence [,mdi'pendsns] n независимость

inflict [m'flikt] у наносить

invincible [m'vmsabl] а непобедимый

might [mait] n мощь

monastic [mg'nasstik] а монастырский

obstacle ['nbstskl] n препятствие

pope [рэир] п папа римский

rebel [n'bel] v восставать

renaissance [ra'neissns] n эпоха Возрождения

rent [rent] л арендная плата

rival ['rarvsl] n соперник

spring [spnrj] v (sprang; sprung) возникать

strive [strarv] v (strove; striven) бороться

strove [straw] v past от strive

tend [tend] v пасти

thoroughly ['влгек] adv совершенно

witness [ 'witngs] v быть свидетелем; видеть

46

47

Columbus [ka'lAmbas] discovered America. Vasco da Gama [ 'vseskau da 'grxma] reached the coast of India making his sea voyage. Magellan [mag'ebn] went round the earth. The world appeared in a new light.

The Copemican [кэи'рз:шкэп] system of astronomy shattered the power of the Catholic Church, and the Protestant Church was set up. Printing was invented in Germany in the 15th century. Schools and universities were established in many European countries. Great men appeared in art, science and literature.

In art and literature the time between the 14th and 17th centuries was called the Renaissance. It was the rebirth of ancient Greek and Roman art and literature. Ancient culture attracted new writers and artists because it was full of joy of life and glorified the beauty of man.

The writers and learned men of the Renaissance turned against feudalism and roused in men a wish to know more about the true nature of things in the world. They were called humanists. Man was placed in the centre of life. He was no longer an evil being. He had a right to live, enjoy himself and be happy on earth.

The humanists were greatly interested in the sciences, especially in natural scierrce, based on experiment and investigation.

These new ideas first appeared in Italy, then in France and Germany, and shortly afterwards in England and Spain.

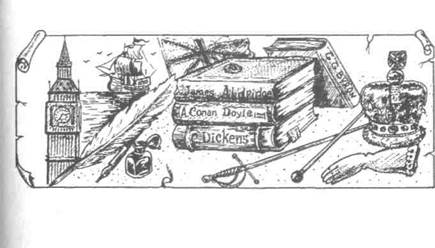

The Italian painters and sculptors Raphael [ 'rasfeial], Leonardo da Vinci [Ira'ncudauda'vmtjl:] and Michelangelo ['maikal 'aendjdau] glorified the beauty of man. The Italian poets Dante [ 'daenti], Petrarch [рэ 'tra;k| and the Italian writer Boccaccio [bt> 'kaljiau], the French writer Rabelias [ 'raebalei], the Spanish writer Cervantes [s3:'vaentiz], and the English writer Thomas More and the poet Shakespeare helped people to fight for freedom and better future.

The renaissance was the greatest progressive revolution that mankind had so far experienced. It was a time which called for giants and produced giants — giants in power, thought, passion, character, in universality and learning. There was hardly any

man of importance who had not travelled extensively, who did not speak four or five languages.

Indeed, Leonardo da Vinci was a painter, sculptor, architect, mathematician and engineer. Michelangelo was a sculptor, painter and poet. Machiavelli [ 'тжкю' veil] was a statesman, poet and historian.

The wave of progress reached England in the 16th century. Many learned men from other countries, for, instance the German painter Holbein, and some Italian and French musicians, went to England. In literature England had her own men. One of them was the humanist Thomas More, the first English humanist of the Renaissance.

Vocabulary

| learned ['b:nid] о ученый phase [feiz] n период rouse [rauz] v возбуждать shatter ['Jaets] v подрывать statesman ['steitsman] n государственный деятель universality [Ju:niV3:'sashti] n универсальность |

denote [di'nsut] v обозначать experience [iks 'pionans] v испытывать, переживать extensively [iks'tensrvh] adv повсюду giant [tfjaignt] n гигант glorify ['gto:nfai] v прославлять investigation [mvesti'geijbn] n расследование

Questions and Tasks

1. What does the word "renaissance" mean?

2. Talk about the great events that gave rise to the movement.

3. What were the different views regarding man in the Middle Ages and during the epoch of the Renaissance?

4. Who were the humanists?

5. In what country did the Renaissance start first?

6. What do you know about the Renaissance in Italy?

7. When did the wave of progress reach England?

48

49

Thomas More

(1478-1535)

|

|

Sir Thomas More [ 'tomas mo:] was born in London and educated at Oxford. He was the first English humanist of the Renaissance. He could write Latin very well. He began life as a lawyer. He was an active-minded man and kept a keen eye1 on the events of his time. Soon he became the first great writer on social and political subjects in English. The English writings of Thomas More include: discussions on political subjects, biographies, poetry.

Thomas More was a Catholic, but fought against the Pope and the king's absolute power. The priests hated him because of his poetry and discussions on political subjects. Thomas More refused to obey the king as the head of the English Church, therefore he was thrown into the Tower of London and beheaded there as a traitor.

The work by which Themas More is best remembered today is Utopia [ju: Чэирю] which was written in Latin in the year 1516. It has been translated into all European languages.

Utopia (which in Greek means "nowhere") is the name of a non-existent island. This work is divided into two books.

In the first, the author gives a profound and truthful picture of the people's sufferings and points out the social evils existing in England at that time. In the second book Thomas More presents his ideal of what future society should be like. It is an ideal republic. Its government is elected. Everybody works. All schooling is free. Man must be healthy and wise, but not rich. Utopia describes a perfect social system built on communist principles. The word "utopia" has become a byword and is used in modern English to denote an unattainable ideal, usually in social and political matters.

1 kept a keen eye — пристально следил 50

Vocabulary

active-minded f'aektiv'mamdid] оэнер- obey [a'bei] v подчиняться

гичный, деятельный profound ['ra'faund] а глубокий

behead [bi'hed] v обезглавливать; каз- traitor f'treita] n предатель

нить unattainable ['лпэЧетпэЫ] о недости-

byword ['baiW3:d] n крылатое слово жимый

composition [_котрэ'гг/эп] п построение

Questions and Tasks

1. Who was the first English humanist of the Renaissance?

2. When did Thomas More live?

3. What kind of man was he?

4. What did the English writings of Thomas More include?

5. Comment on the composition of his best work Utopia.

6. What was More's idea of what future society should be like?

7. What did Thomas Moore fight against?

8. Why was Moore thrown into the Tower of London and beheaded?

THE DEVELOPMENT OF DRAMA IN ENGLAND

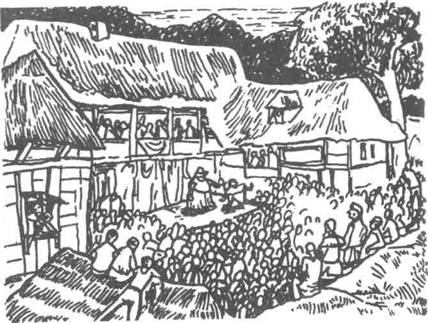

During the Renaissance art and literature developed. People liked to sing and act. Drama became a very popular genre of literature. The Renaissance dramas differed greatly from the first plays written in the Middle Ages. As in Greece drama in England was in its beginning a religious thing. The clergymen began playing some parts of Christ's life in the church. The oldest plays in England were the "Mysteries" and "Miracles" which were performed on religious holidays. These were stories about saints and had many choral elements in them.

Gradually ceremonies developed into performances. They passed from the stage in the church to the stage in the street. At the end of the 14th century the "Mysteries" gave way to the "Morality" plays. The plays were meant to teach people a moral lesson. The characters in them were abstract vices and virtues.

Between the acts of the "Morality" and "Miracle plays" there were introduced short plays called "interludes" ['intaluxlz] — light

51

Actors showing a performance outside a country inn

compositions intended to make people laugh. They were performed in the houses of the more intelligent people.

Longer plays in which shepherds and shepherdesses took part were called "Masques" [ 'ma:sks]. These dramatic performances with music were very pleasing and were played till the end of the

17th century.

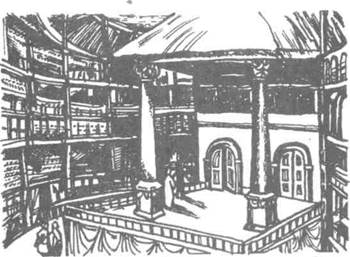

Soonthe plays became complicated. Professional actors travelled from town to town performing in inn yards. The first playhouse in London was built in 1576. It was called "The Theatre". A more famous theatre was the "Globe", built in 1599. It was like the old inn yard open to the sky. Galleries and boxes were placed round the yard. The stage was in the middle of it. There was no scenery. The place of action was written on a placard, e. g., a palace, London, etc. There was no curtain, either. The actors stood in the middle of the audience on the stage. Women's parts were acted by boys or men.

Drama from its very beginning was divided into comedy and tragedy. The first English tragedies and comedies were performed in London in about 1550.

In the 16th century a number of plays were written in imitation of Ancient Roman tragedies and comedies. There was little action on the stage. The chorus summed up the situation and also gave moral observations at the end of each act. Such plays were called classical dramas. The greatest playwrights of the time were men of academic learning, the so-called "University Wits".

Among the "University Wits" were John Lyly1, Thomas Kyd2, Christopher Marlowe and others. Each of them contributed something to the development of the drama into the forms in which Shakespeare was to take it up.

Vocabulary

| masque [ma:sk] л маска miracle fmirakl] л чудо mystery ['mistsn] л тайна observation [^пЬгэ'ует/эп] л наблюдение placard ['plsekard] n афиша; плакат scenery ['si:ngn] л декорации shepherdess ['Jepsdis] л пастушка sum (up) [saiti] v подводить итог, суммировать vice [vais] л зло virtue ['v3:tju:] л добродетель |

box ['bnks] n ложа ceremony ['senmsni] л церемония; торжество choral ['кэ:гэ1] а хоровой chorus ['ko:rgs] n хор complicated ['ktmrplikeitid] о сложный gallery ['дэе1эп] л балкон, галерея genre [за:пг] л жанр gradually ['grsedjrali] л постепенно intend [m'tend] л предназначать interlude ['mtaluxl] л интерлюдия introduce [mtre'djiKs] л вставлять, помещать

Questions and Tasks

1. What became a very popular genre of literature during the Renaissance?

2. Describe the Renaissance dramas.

3. What were the oldest plays in England?

4. When did the "Mysteries" give way to "Morality" plays?

5. What plays were called "Masques"?

John Lyly [ 'lih] (1554— 1606) —Джон Лили, англ. писатель и драматург Thomas Kyd (1558 — 1594) — Томас Кид, англ. драматург

52

53

6. Describe the Globe theatre, built in 1599.

7. Talk about the first plays written in imitation of Ancient Roman tragedies and comedies.

8. What were the names of the greatest playwrights of the time?

9. Who were among the "University Wits"?

to reveal the suffering of man. Marlowe introduced blank verse in his tragedies and pointed out the way to William Shakespeare, the greatest of the Renaissance humanists. In imagination, richness of expression, originality and general poetic and dramatic power he is inferior to Shakespeare alone in the 16th century.

Christopher Marlowe (1564-1593)

Christopher Marlowe (1564-1593)

|

|

Christopher Marlowe [ 'kristsfa 'ma:bu] was a young dramatist who surpassed all his contemporaries. His father was a shoemaker in Canterbury. Christopher Marlowe studied at Cambridge University and was greatly influenced by the ideas of the Renaissance. Almost nothing is known of his life after he left the University. He was killed at a tavern at the age of twenty-nine.

| Christopher Marlowe |

Christopher Marlowe is famous for his four tragedies: Tamburlaine ['tajmbalein] the Great; Doctor Faus-tus ['fo:stas]; The Jew of Malta ['molts] and Edward II.

Marlowe approached history from a Renaissance point of view. His tragedies show strong men who fight for their own benefit. No enemy can overcome them except death. They are great personalities who challenge men and gods with their strength.

Doctor Faustus is considered to be the best of his works. Marlowe used in it the German legend of a scholar who for the sake of knowledge sold his soul to the devil. Dr. Faustus wants to have power over the world: "All things that move between the quiet poles shall be at my command". The devil serves him twenty-four years. When Faustus sees the beautiful Helen he wants to get his soul back. It is too late.

Marlowe's plays taught people to understand a tragedy which was not performed just to show horror and crime on the stage, but

Vocabulary

approach [s'prautj] v подходить inferior [т'йэпй] п стоящий ниже

blank verse ['bter)k'v3:s] n белый стих overcome [ 'эотэклт] v (overcame;

challenge ['tfaslmcfe] v вызывать на со- overcome) побороть, преодолеть

ревнование reveal [n'vi:l] v показывать

contemporary [кэп'temparan] n совре- scholar ['sknlg] n ученый

менник soul [saul] n душа

devil ['devil] n дьявол surpass [s9'pa:s] v превосходить

for the sake of ради tavern ['taevan] n таверна

horror ['гтгэ] п ужас

Questions and Tasks

1. Tell the main facts of Marlowe's life.

2. What is Marlowe's famous for?

3. Comment on his tragedies.

4. What is considered to be the best of his works?

5. What can you say about the plot of Doctor Faustus?

6. Speak on the meaning of Marlowe's plays.

William Shakespeare (1564-1616)

The great poet and dramatist William Shakespeare was a genius formed by the epoch of the Renaissance.

He is often called by his people "Our National Bard" (bard = a singer of ancient songs, a poet), "The Immortal Poet of Nature" (When the English people called Shakespeare "the poet of Nature" they meant "the poet of realism", but they didn't know such a word then) and "the Great Unknown". Indeed very little can be told about his life with certainty, as no biography of Shakespeare was published during his life time nor for 93 years after his death.

54

55

|

|

Yet, patient research by certain scholars has uncovered the biography, but not fully.

| William Shakespeare |

William Shakespeare was born at Stratford-on-Avon feivan] on the 23rd of April, 1564. His father, John Shakespeare, was a farmer's son, who came to Stratford in 1551 and became a prosperous tradesman. John Shakespeare was elected alderman and later by the time his eldest children were born he acted as bailiff which meant he had to keep order in the town according to the local laws. John Shakespeare was illiterate; he marked his name by a cross because he was unable to write it.

His mother, Mary Arden [' mean ' a:dn] was a farmer's daughter. John and Mary had eight children, four girls and four boys, but their two eldest daughters died at an early age. The third child was William. William was a boy of a free and open nature, much like his mother who was a woman of a lively disposition. Of Shakespeare's education we know little, except that for a few years he attended the local grammar school where he learned some Latin, Greek, arithmetic and a few other subjects. His real teachers, meanwhile, were the men and women around him. Stratford was a charming little town in the very centre of England. Near at hand was the Forest of Arden, the old castles of Warwick and Kenilworth, and the old Roman camps and military roads. The beauty of the place must have influenced powerfully to the poet's imagination.

When Shakespeare was about fourteen years old, his father lost his property and fell into debt and so the boy had to leave school and help his family. On leaving school, William Shakespeare began to learn foreign languages. His father had an Italian in his house who was quite a good scholar. This Italian taught William the Italian language, brushed up his Latin and studied the poetry of many Latin, Greek and Italian authors with him.

William was still a boy when his first poems appeared. Writing poems was very common in Shakespeare's days. It was called son-

netising [' sonitaizin]. His future wife Anne Hathaway [' sen' haeQawei] also expressed her feeling for William in verse. Anne and William met by the river Avon, and she calls him "Sweet Swan of Avon". In his nineteenth year William Shakespeare married Anne Hathaway, the daughter of a well-to-do farmer. They had three children — Susanna [su: 'zaena], and the twins, Judith [ 'd^urdiG] and Hamnet. A few years later after his marriage, about the year 1587, Shakespeare left his native town for London.

At this time the drama was gaining rapidly in popularity through the work of the University Wits. Shakespeare soon turned to the stage and became first an actor, and then a "play patcher", because he altered and improved the existing dramas. Thus he gained a practical knowledge of the art of play writing. Soon he began to write plays of his own, first comedies and then historical plays. New plays by William Shakespeare appeared almost every year between 1590 and 1613, in some years one play, more often two.

|

|

| Shakespeare's birthplace |

| ) |

In 1593 and 1594 he published two long poems — Venus and Adonis ['vi:nas and a 'dauniz] and Lucrece [ 'lu:kri:s]. Both poems were dedicated to the young Earl of Southampton f sauQ' aemptan], a great admirer of Shakespeare's plays. Until Shakespeare printed his poems the public had no idea he was a poet. He was known as an actor and a writer of plays. At that time playwrights wrote for a definite theatrical company, and the theatre became the owner of the play. Shakespeare's plays were very popular. Actors and writers

56

57

respected him and admired his genius. As his popularity with the people grew, the aristocracy too became interested in his work. When Queen Elizabeth wanted to see a play, she usually ordered a performance at court.

In 1594 Shakespeare became a member of the Lord Chamberlain's ['tfeimbalmz] company of actors. He wrote plays for the company and acted in them. His early plays were performed in the playhouses known as "The Theatre" and "The Curtain". When the company built the "Globe" theatre most of his greatest plays were performed there. By that time Shakespeare was acknowledged to be the greatest of English dramatists. His career as a dramatist lasted for nearly twenty-one years. His financial position also improved. He was a shareholder of the "Globe" theatre and he purchased property in Stratford and in London. But the years which brought prosperity also brought sorrows. He lost his only son, his brother and parents.

In spite of prosperity he must have left lonely among the people surrounding him. In 1612 he returned to Stratford-on-Avon for good. The last years of his life Shakespeare spent in Stratford. He died on the 23rd of April 1616. He is buried in his native town Strat-ford-on-Avon. In 1616 a month before his death he wrote his will.

On his tomb there are,four lines which are said to have been written by William Shakespeare:

Good friend, for Jesus' sale forbear To dig the dust enclosed here; Blessed be he that spares these stones, And cursed be he that moves my bones.

These lines prevented the removal of his remains to Westminster Abbey; only a monument was erected to his memory in Poets' Corner.

Vocabulary

acknowledge [sk'rrohcfc] v признавать alter ['э:кэ] v переделывать

admirer [ad'maiara] n поклонник bailiff ['beilif] n судебный пристав

alderman ['э:Шэтэп] п олдермен, член bless [bles] v благословлять

муниципалитета brush up [ЬглГ] v заниматься

| lively ['laivli] а живой patcher ['paet/э] n работник, производящий мелкий ремонт prevent [pn 'vent] v мешать, не допускать property [ 'propati] n собственность, имущество prosperous fprosparas] а состоятельный prosperity [pros'panti] n процветание, успех purchase ['p3:tjbs] v покупать remains [ri'memz] n останки, прах removal [n'murvsl] n перемещение research [n's3:tf] n исследование, изучение shareholder ['/еэ,пэиЫэ] п акционер sonnetise ['snnatarz] v сочинять сонеты spare [spea] v сберегать tomb [tu:m] n надгробный памятник well-to-do ['welts'du:] а состоятельный |

certainty ['s3:tnti] л уверенность common ['кшттэп] а обычный company [ 'клтрэш] п театральная

труппа confer [кэпТз:] a title давать титул curse [k3:s] v проклинать debt [det] n долг dedicate ['dedikeit] v посвящать definite ['defmit] а определенный disposition [^disps'zifgn] n характер epoch ['i:pDk] n эпоха erect [1'rekt] v воздвигать financial [fai'nasnfsl] а финансовый forbear [fo:'bes] v (forbore; forborne)

воздерживаться gain [gem] v добиться genius ['cfemjss] n гений illiterate [r'litarit] а неграмотный immortal [i'mo:tl] а бессмертный Jesus ['djfczss] n Иисус

Questions and Tasks

1. What titles have the English people conferred on William Shakespeare?

2. Where was Shakespeare born?

3. When was he born?

4. What did his father, John Shakespeare, do?

5. How many children did John and Mary Shakespeare have?

6. What kind of boy was William?

7. What do we know of Shakespeare's education?

8. What must have influenced powerfully to the poet's imagination?

9. What happened when William was about fourteen years old?

10. When did his poems begin to appear?

11. When did he marry Anne Hathaway?

12. How many children did they have?

13. Talk about the first period of Shakespeare's life in London.

14. What poems did he publish in 1593 and 1594?

15. To whom were these poems dedicated?

16. When did he become a member of the Lord Chamberlain's company of actors?

17. Where were most of Shakespeare's plays performed?

18. Prove that his financial position improved.

19. When did Shakespeare return to Stratford-on-Avon?

20. When did he die?

58

59

Shakespeare's Literary Work

William Shakespeare is one of those rare geniuses of mankind who have become landmarks in the history of world culture.

Poet and playwright William Shakespeare was one of the greatest titans of Renaissance.

A phenomenally prolific writer, William Shakespeare wrote 37 plays, 154 sonnets and two narrative poems. Shakespeare's plays belong to different dramatic genres. They are histories (chronicle plays), tragedies, comedies and tragic-comedies.

Shakespeare's literary work is usually divided into three periods:

• The first period — from 1590 to 1601 — when he wrote histories, comedies and sonnets.

• The second period — from 1601 to 1608 — was the period of tragedies.

• The third period — from 1608 to 1612 — when he wrote mostly tragic-comedies.

These three periods are sometimes called optimistic, pessimistic and romantic.

Vocabulary

landmark ['laendma:k] n веха prolific [prs'lifik] а плодовитый

narrative ['nseratrv] а повествовательный rare [геэ] а редкий

phenomenally [fi'rrommli] adv необык- titan ['taitgn] n титан

новенно

The First Period Comedies

The first period is marked by youthful optimism, great imagination and extravagance of language. In these years Shakespeare created a brilliant cycle of comedies. They are all written in his playful manner. The gay and witty heroes and heroines of

The Globe

comedies come into conflict with unfavourable circumstances and wicked people. But their love and friendship, intellect and faithfulness always take the upper hand1.

The comedies are written in the bright spirit of the Renaissance. The heroes are the creators of their own fate, that is to say they rely on their cleverness to achieve happiness. Shakespeare trusted man's virtues and believed that virtue could bring happiness to mankind. Shakespeare was optimistic, therefore love of life is the main feature of his comedies, notable for their wit, comic characters and situations, for the smoothly flowing language and harmonious composition. Shakespeare's comedies were written to take the spectator away from everyday troubles. In them people lived for merriment, pleasure and love.

The best comedies of that period are:

Love's Labour's Lost— 1590,

The Comedy of Errors — 1591,

The Two Gentlemen of Verona [уГгэипэ] — 1592,

A Midsummer Night's Dream — 1594,

1 take the upper hand — побеждают

60

61

The Merchant of Venice ['vems] — 1595,

The Merchant of Venice ['vems] — 1595,

The Taming of the Shrew [fru:] — 1596,

Much Ado About Nothing — 1599,

The Merry Wives of Windsor ['wmza] — 1599,

As You Like It — 1600,

Twelfth Night — 1600.

Twelfth Night

Twelfth Night is one of the most charming and perfect of Shakespeare's plays. It was the last of his merry comedies. Afterwards he wrote mainly tragedies. The play was written to say good-bye to the Christmas holidays which were celebrated with great pomp and lasted for twelve days. Twelfth Night was the end of merry-making. Hence the title of the comedy.

The plot of the play is centred round Viola ( vaiab]. She is a clever, intelligent and noble-hearted woman. Making a sea voyage she and her twin brother Sebastian [si 'baestjan] are shipwrecked on the coast of Illyria governed by Duke Orsino [of si:rau]. The captain of the ship

brings Viola safe to shore. Her brother has apparently drowned. The captain tells Viola that Duke Orsino is in love with Countess Olivia [t> '1тэ] whose father and brother have recently died. For the love of them she avoids people. Viola wishes to serve this lady, but Olivia admits no person into her house. Then she makes up her mind to serve Orsino as a page under the name of Cesario [si 'zemau]. She puts on her brother's clothes, and looks exactly like him. Strange errors happen as the twins are mistaken for each other.

The Duke is fond of Cesario and tells him about his love for Olivia and sends him to her house to talk to her about his love. Viola goes there unwillingly because she herself loves Orsino.

On seeing Cesario Olivia falls in love with him, "I love thee1 so, that, in spite of your pride, nor wit nor reason can my passion hide". ; In vain, Cesario's resolution is "never to love any woman". In the meantime Sebastian comes to Olivia's house, she mistakes him for Cesario and proposes they should marry. Sebastian agrees. Soon Cesario — Viola enters. Everybody wonders at seeing two persons with the same face and voice. When all the errors are cleared up, they laugh at Olivia for falling in love with a woman. Orsino, seeing that Cesario would look beautiful in a woman's clothes, says to him that for the faithful service Viola has done for him so much beneath her soft and tender breeding, and since she has called him master so long, she should now be her master's mistress, and Orsino's true duchess. The twin brother and sister are wedded on the same day: Viola becomes the wife of Orsino, the Duke of Illyria, Sebastian — the husband of the rich and noble Countess Olivia.

In the character of Viola Shakespeare embodied the new ideal of a woman, which was very different from that of feudal times. The woman described in the literature of the Middle Ages, especially in the romances, were shown as passive objects of love.

Shakespeare shows that women have the right to equality and independence. Viola defends her right to happiness and love.

The stage where "Tweifth Night" was performed

1 thee — you

62

63

Vocabulary

admit [ad'mit] v допускать

apparently [s'peeranth] adv очевидно; по-видимому

avoid [a'void] v избегать

breeding ['bri:dirj] n воспитание

countess ['kauntis] n графиня

cycle ['saikl] n цикл

drown [draun] v тонуть

duchess ['d\tjis] n герцогиня

embody [im'bndi] v воплощать

error ['era] n ошибка

extravagance [iks'trsevigans] n экстравагантность

feature ['fi:tfa] л черта

harmonious [hafmaunjas] а гармоничный

Sonnets

hence ['hens] adv отсюда merriment ['menmant] n веселье notable ['nautabl] а известный, выдающийся pomp [primp] n помпа, пышность propose [ргэ 'pauz] v делать предложение (о браке) rely [n'lai] v полагаться, доверять smoothly ['smvxdh] adv плавно tender ['tends] а нежный, заботливый twin [twin] n близнец unfavourable [лп 'feivarabl] а неблагоприятный wicked ['wikid] а злой witty ['witi] а остроумный

Sonnet 66

Tired with all these, for restful death I cry, As, to behold1 Desert a beggar born, And needy Nothing trimm'd in jolity2 And purest Faith unhappily forsworn,3

And golded Honour shamefully misplaced, And maiden Virtue rudely strumpeted4 And right Perfection wrongfully disgraced, And Strength by limping Sway5 disabled,

And Art made tongue — tied by Authority, And Folly doctor-like6 controlling Skill, And simple Truth miscall'd Simplicity,7 And captive Good attending captain 111.8

Tired with all these, from these would I be gone, Save9 that, to die, I leave my love alone.

The sonnet is a poetical form that appeared in Italy in the 14th century. It was introduced into English literature during the first period of the Renaissance. Shakespeare's sonnet has 14 lines. It is divided into three stanzas of four lines with a final rhyming couplet ['k/vpht].