Automobile Fuel Economy and Greenhouse Gas Emissions Standards

(http://cse.ucpress.edu/content/early/2017/10/12/cse.2017.000380#F3)

Grady Killeen and Arik Levinson

Abstract

In March 2017, EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt reopened an evaluation of the automotive fuel economy and greenhouse gas emissions standards that the EPA had finalized in January. This case provides a history of the rules, along with assessments of their costs and benefits. It addresses numerous debates, including the environmental benefits of the rules, the role of electric vehicles, whether the standards should be less strict for larger cars, and tradeoffs between fuel economy and safety.

KEY MESSAGE

This case describes the history and details of American automobile environmental and fuel economy standards, in sufficient detail for students to be able to have an informed discussion as to their merits. Students should be able to articulate the tradeoffs between the per-mile standards and alternative regulations, describe the rebound effect and how that relates to the estimated costs and benefits of the standards, discuss the pros and cons of weaker standards for larger cars and trucks, and enumerate components of the benefits, including value of a statistical life, the social cost of carbon, accident risk, and congestion.

INTRODUCTION

In January, 2017, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Administrator Gina McCarthy finalized the greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions rules for cars and light trucks through 2025, saying they will save American drivers billions of dollars at the pump while protecting our health and the environment. Two months later, the new EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt reversed that decision: “These standards are costly for automakers and the American people. We will work with our partners at DOT to take a fresh look to determine if this approach is realistic. This thorough review will help ensure that this national program is good for consumers and good for the environment”. By statute, that EPA review is due by April 1, 2018.

CASE EXAMINATION

Background

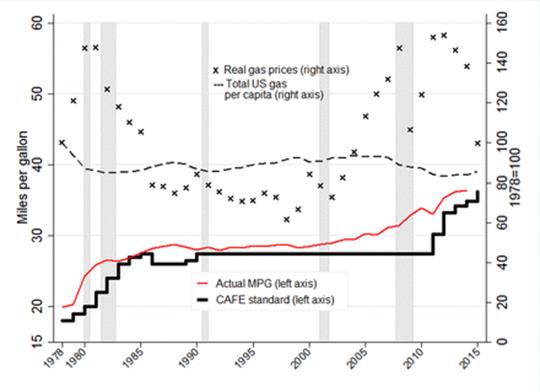

In 1975, the U.S. Congress passed the Energy Policy and Conservation Act, which gave the Department of Transportation (DOT), the authority to set and enforce fleet average miles per gallon (mpg) targets for new cars and light trucks sold in the United States. The new regulations, called Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) standards, climbed quickly to their statutory maximum of 27.5 mpg for cars, where they remained for the next two decades. Since 2011, the CAFE standards have been modified in several ways: they have increased in stringency, are relatively less strict for larger cars, and are tradable among carmakers. Table 1contains a timeline for important events in the development of the policy and this case study.

|

|

|

The New Administration’s Changes

In May 2009, President Obama announced that beginning in 2012, automobile manufacturers would be required to meet standards for both fuel economy and GHGs. DOT would continue overseeing fuel economy, while EPA would monitor GHGs, requiring cooperation between the agencies. To comply with EISA’s requirement that the new standards be attribute based, the new rules set mpg targets that differed based on vehicles’ sizes, as measured by their footprints—the area under the vehicles’ four tires. Cars and trucks with larger footprints would have lower mpg targets. EPA and DOT finalized that rule in 2010, for model years 2012–2016.

How the Rules Work in Practice

Before 2011, regulatory compliance had been based on the sales-weighted average fuel economy of each manufacturer’s car or light truck fleet sold in the United States. If that average fell short of the target mpg, a fee of US$5.50 would be imposed for each tenth of an mpg below the target, multiplied by the number of vehicles sold . Figure 2 plots total fines paid each year.

Дата добавления: 2019-09-08; просмотров: 410; Мы поможем в написании вашей работы! |

Мы поможем в написании ваших работ!